Sailmaker Daryl Morgan gives some expert advice on ocean sails, while Neil Smith explains how his family coped with delaminating sails

Daryl Morgan: choosing offshore sails

A transatlantic crossing is a trip of a lifetime. Maybe you’ve sold your house to do it, or taken a mortgage on a boat. You don’t want to be let down by your sails.

It sounds like Blue Pearl (see below) had carbon sails with taffeta, a very lightweight loosely woven fibre added for its UV resistance.

The kind of failure Neil Smith describes is uncommon for laminate sails.

Rather than the glues having perished, which is unlikely, the sails may have suffered from water ingress, flogging, fatigue and UV degradation.

The ones he describes are relatively large sails – possibly a second fit – and maybe the material was chosen for JOG racing, coastal hopping or trips to France and back.

Daryl Morgan, technical manager at Bainbridge International.

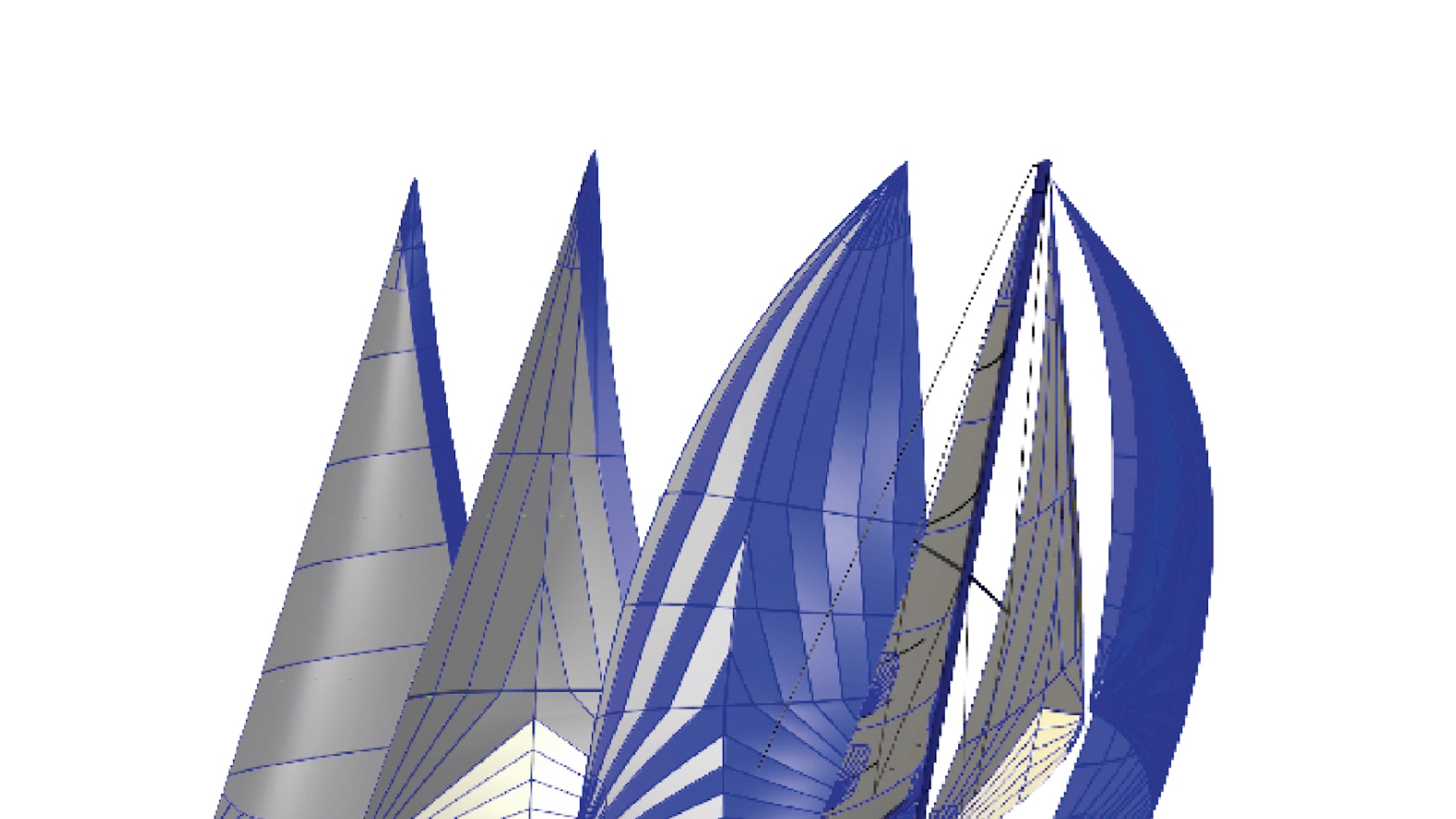

When people start doing events, they tend to go for a laminate for its weight-saving advantage and performance.

However, if you’re doing a round-the-world, or passage of 2,000 miles or more, you want a durable, bulletproof, repairable set of sails.

The average sailmaker in Tahiti is not going to have a specialist hot-glue machine, ultrasonic tape, and sticky-back Kevlar or carbon fibre repair material. Nor will they have specialised sewing machines.

If you sew a laminate in a machine it’s like the stitch of death – it’ll perforate like a sheet of paper torn down the dotted line. You don’t want to go anywhere near that!

A lot of these places in the wilderness, these lovely exotic islands, they’ll have a little straight stitching machine, and the sailmakers are used to working with natural fibres.

Laminates are a totally different kettle of fish.

Offshore sails: Woven sailcloths

You could maybe reef a sail in a flat calm in five minutes, but in the dark, in horrible conditions when you’re exhausted, it could take 35-45 minutes.

Meanwhile the sail’s thrashing and around with possible permanent distortion due to the off-thread line loads put into the sail while reefing.

A woven sailcloth is just going to hang on in there. It will handle the occasional flogging and misuse, with the bonus that you will get from A to B safely.

When things go wrong, you don’t want a laminate; having any kind of exotic aramids such as carbon or kevlar is asking for trouble.

Think about your usage when choosing offshore sails. Woven cloths are easier to handle and can withstand being thrashed around

Dacron sails will do everything they need to. Woven dacrons or hybrid dacrons, combining modern fibres such as Vectran and HMPE (high modulus polyethylene, more commonly known by trade names Spectra or Dyneema) are a really good choice for long-distance cruising sails.

Dacron is a woven fabric, not laminated, so there are no layers to fall apart.

HMPE and Vectrans will increase the strength of the woven polyester sailcloth and the overall longevity and durability, plus increase the resistance to tear.

For tropical climes and passages a woven sailcloth will always do the job.

Offshore sails: cruising laminates

For cruising and inshore passages there’s a product called a cruise laminate.

It’s a blend of polyester load bearing yarns with adhesives, sandwiched between films with a lightweight taffeta on the outside to increase chafe resistance and UV stability.

Continues below…

BA pilot snaps brother-in-law sailing 38,000ft below

When Michael Terry set sail across the Atlantic in the ARC+ rally, he had no idea he’d be seen from…

How to measure your yacht for new sails

Measuring your boat for new sails is a job for the sailmaker, so when our PBO Project Boat Maximus needed…

What are the different types of sailcloth and design?

Before speaking to your sailmaker, it’s worth knowing the different types of sailcloth on the market so you can understand…

Quiz a sailmaker – everything you need to know about sails

Whilst deciding what cut and sailcloth to chose for the PBO Project Boat, we quizzed technical manager Daryl Morgan from…

It’s good for normal everyday cruising, and is generally cut in a radial configuration so has good load-bearing, great shape and longevity.

But for extended passages, a woven construction sail is still much better.

Sail repairs

For sail repairs, you’re going to need some cloth that matches, or is similar to, the materials you already have.

You can use Bainbridge Insignia tape, which is sticky-backed, in 45m rolls from 15mm to 80mm thickness, and this can be used all over the place.

You’ll need sailmaker’s palms and a mix of needles, wax thread and webbing – which you might need to back-up rings you pulled out.

A roll of Dacron tape is handy, you can stick it onto the sail and then, for a wider repair, attach some Insignia cloth, which is a lightweight, adhesive-backed polyester used for insignias, numbers and emergency repairs.

Bainbridge also does an offshore sail repair kit which comes with a variety of items including patches, palm, scissors and tape.

Performance sails are great until something goes wrong

I’d suggest using this as a starter kit and building from there.

I’ve known some really big boats repair sails with glues such as 3M’s 5200 marine adhesive.

Superglue will work, but it gets quite stiff. I’d only use it to hold the parts in place while fixing on the plastic laminate.

There was a time when you used to join the sailcloth together using Superglue but there are better adhesives now.

It’s also a good idea to have a small sewing machine, some thread and spare needles.

Remember, the repair might be strong enough to get you ashore, but any sticking or hand-stitched repairs will then need to be removed and replaced properly by a sailmaker.

Speak to your sailmaker If you’re getting new sails made it’s completely reasonable to ask for some of the excess cloth, or even if you’re not, you could explain what you’re doing to your local sailmaker, and ask if they have something suitable for repairs.

They’ll have offcuts that would otherwise go in the bin.

Get to know your local sailmaker, look after them and they’ll look after you. They may stock sail repair kits and offer you other things suitable for your sails.

Finally, when you’re doing a long passage, put chafe patches absolutely everywhere.

Do you want your sail in one piece at the end? Anywhere you see it rubbing, patch it, and check it as you would your halyards.

Our sail disaster on Blue Pearl

Neil Smith. Credit: James Mitchell

Neil Smith: “Our sails came with the boat, Blue Pearl, a Moody 54 which we bought two years ago with an Atlantic crossing in mind. We had them checked over by a company in Santander and they were deemed to be fine for an ocean passage.

“We set off from Spain for the start of the ARC+ rally thinking we had good sails. However, the foresail – the yankee – started to delaminate. It was made of two layers with a carbon fibre mesh in between, and the glue appeared to be perishing. There were large tears coming up between the seams and we had to drop the sail and hand-stitch it twice while going along, and once in Porto Santo.

“We didn’t have bad weather – it wasn’t due to the wind, just wear and tear. The first I knew of it was on a night watch. I looked up and thought, ‘That sail looks transparent – I can see the stars through it!’ I got my torch and shone it through the middle and saw a 2m split, with all the black gaping out of the middle of the sail.

“When stitching, it was so difficult to match the parts together – the net, mesh and two outer layers. We couldn’t get it back to where it was. There was just so much of it to do! We only did two to three stitches in every metre or so, to tack it.

Neil Smith and his cruising family aboard Blue Pearl. Credit: James Mitchell

“After the second day, we realised it wasn’t going to be any good. We stopped in Madeira and rang ahead to Rolly Tasker Sails in Gran Canaria. We told him the sizes. He came to the boat to measure up, we paid a 70% deposit and they were manufactured in five weeks, and delivered a week and a half later.

“We ordered a new mainsail too, as our original was made from the same material, and though it was stitched differently along the seams, we feared it might also go, especially as it had got stuck at one point in the furler.

“The new sails are 11oz Dacron, and seem to be fairly good quality and a reasonable price. For the yankee, I made enquiries and got costs ranging from €5,000 to €25,000 for high-tech sails that would probably only last five years. Let’s face it, you can buy five plain Dacron sails for the cost of one of those, and a baggy sail will still work, even if it’s not quite as efficient.”

Enjoy reading Offshore sails: What you need to cross the Atlantic?

A subscription to Practical Boat Owner magazine costs around 40% less than the cover price.

Print and digital editions are available through Magazines Direct – where you can also find the latest deals.

PBO is packed with information to help you get the most from boat ownership – whether sail or power.

-

-

-

- Take your DIY skills to the next level with trusted advice on boat maintenance and repairs

- Impartial in-depth gear reviews

- Practical cruising tips for making the most of your time afloat

-

-

Follow us on Facebook, Instagram, TikTok and Twitter