Fully battened or semi-battened? Do you need a storm jib? And what about cloth and cut? We quiz a sailmaker on different sails for different budgets

Whilst deciding what cut and sailcloth to chose for the PBO Project Boat, we quizzed technical manager Daryl Morgan from Bainbridge International – one of the world’s oldest sailcloth manufacturers – about sailmaking.

What tools did sailmakers use before computers?

A sailmaker would always have a set of drawing board tools such as a trusty scale ruler, pencil, protractor, calculator; those sort of items. You’d sit at a drawing board and start pencilling out the sails to a scale of 1:50.

The downside of paper and pencil, is you only get a 2D aspect of the sails. They’re flat. With more advanced computer software these days you can describe the sail’s aerofoil shape.

Is sail design a lot quicker these days?

It’s more about the accuracy. To create the rig, pencil and paper is actually super-fast, especially when you’re as old as me, but to cut the sail and design the sail shape, a computer wins every time. If it’s a standard mould, nothing flash, you can do it in 15 minutes. In the old days, when you chalked out on the floor, it would also take 15 minutes, but you had to draw it to the actual size. If your sail was 30ft by 10ft you’d need that much floorspace. You’d then lay the panels out and give it all to a machinist. Nowadays it’s done on a little A4 screen and away you go.

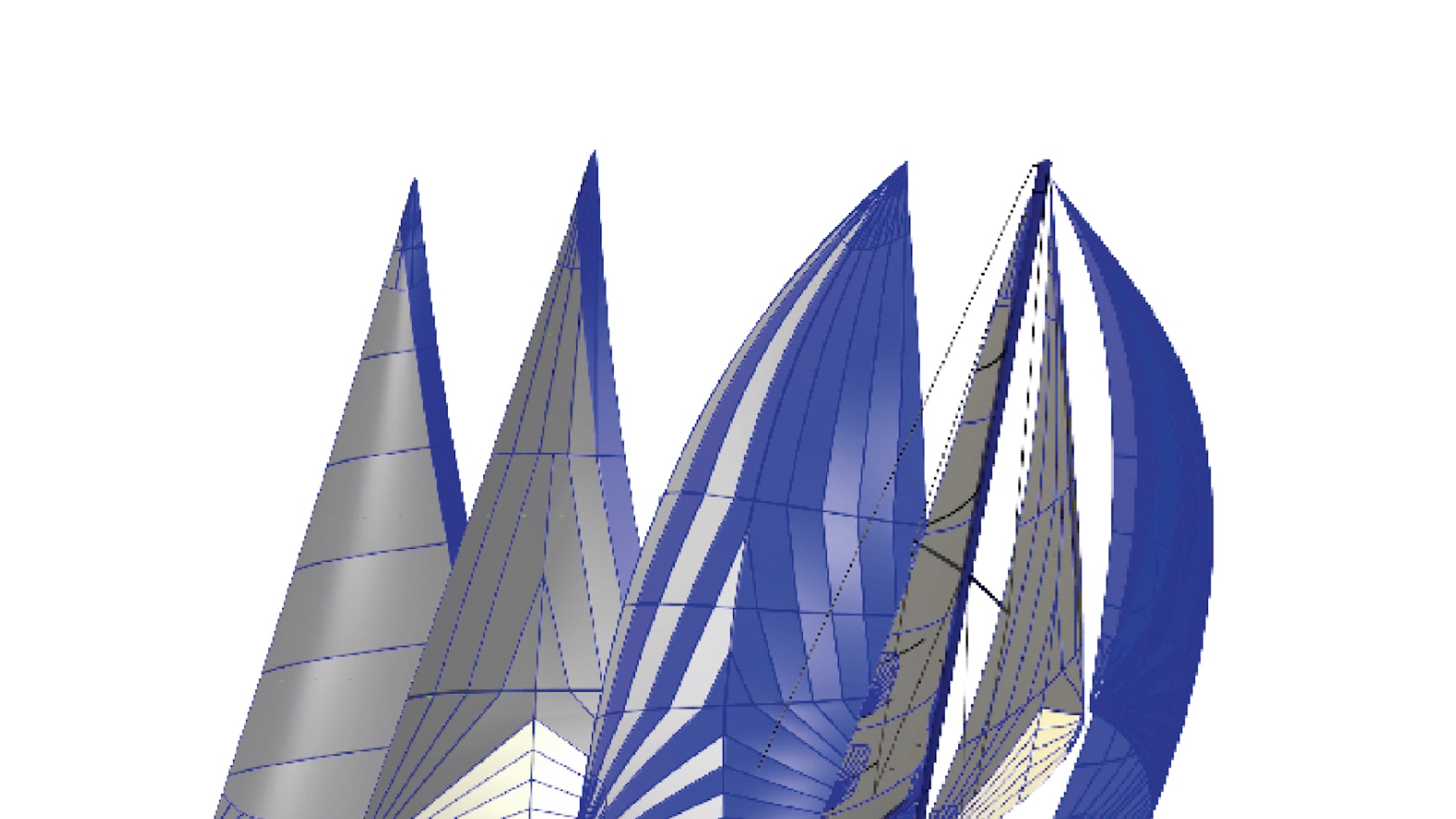

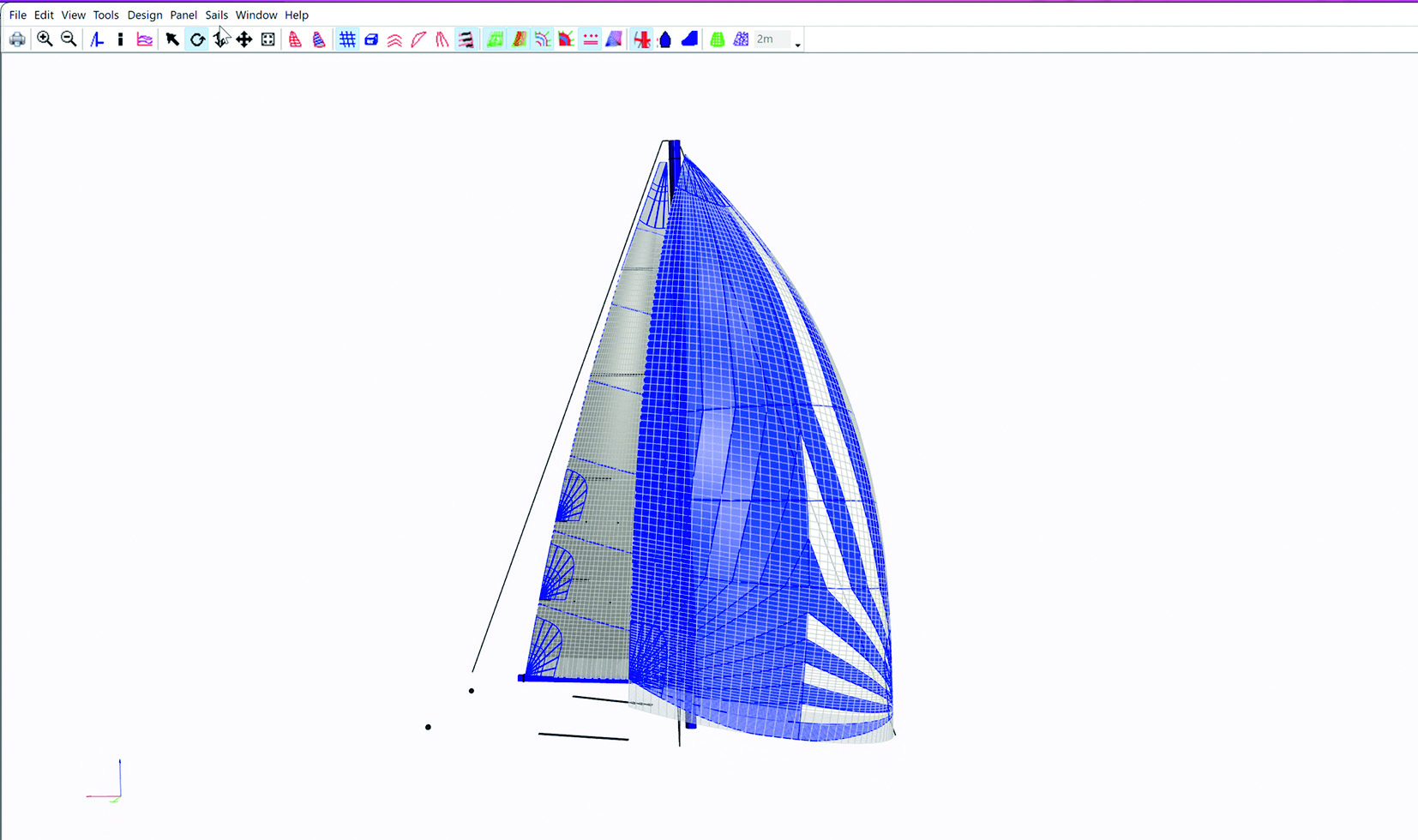

What detail do you get with 3D sail design?

We can see how the sail sits on the main and boom, check the clew height is correct so that the sail sheets correctly onto the track, and doesn’t impact the rig by crashing into the spreaders, for example. You couldn’t do that with pencil and paper, but with foil shapes now on the computer you can describe rod size, wire, shrouds, spreaders, etc. and zoom in to get really accurate detail. You can look at the flying shape and height of all three sails in combination – main, headsail and cruising chute. We’ve gone as accurate as we need to be with the Maxi 84, but for a really big racing boat project we’d drill down even further.

What are the benefits of fully battened sails?

Lot of sails are fully battened, ie battens that stretch the whole width of the sail, from leech to luff. This increases longevity, helps prevent flutter and general abuse. If sailing single-handed, you can go fully battened with a set of lazy jacks and stack pack arrangement so that when the sail drops it’s guided down into the boom bag out of the way. It’s very easy. The battens control the sail. It’s not going to fall off the boom and flop all over the place.

What are the downsides to fully battened sails?

The downside of a fully battened sail is that when hoisting and lowering you need pressure cars on the luff because of the increased friction from the full length of the battens. They work on compression; the batten pushes into the mast, so when hoisting and lowering, you need something to release compression and reduce friction. Hoisting is relatively easy, but lowering is what it’s all about. You need to be able to reef or lower the sail quickly in an emergency. There’s also a bit of extra cost for hardware and longer battens, but to be frank, these days, the costs have gone down and it’s a viable option. We’ve been making our own range of batten cars for 30 years. They’re a proven design, they won’t fail.

What’s a typical batten setup?

A lot of sails are hybrid these days, so a 1 plus 3, or a 2 plus 2, where the top ones are full length and the lower 40% the width of the sail. This reduces cost, compared to a fully battened main, as you have fewer batten cars. The sail low down is less likely to flog anyway, and it’s easier to fit the reefing points.

What’s the J measurement on a yacht?

The J measurement is the length of the foredeck from the stemhead fitting at the tack to the front face of the mast. So the clew location for a 130% overlapping headsail, for example, is J x 1.3, or 130% of the J measurement.

That 135% is a really nice all-round size for a roller furling headsail. It can do the whole range of wind and sea conditions you can expect on a cruising boat; you can sail at 5 knots and also at 25 knots. That’s a lot of range for one sail.

How do furling headsails compare to hanked on sails?

On a furling headsail, a good overlap with the genoa is 135%, the LP. Previously, with hanked-on sails, you’d have had number 1, which is a 150% overlap, a number 2, which is 140% and number 3, which was lower still, as well as a working jib at 80%.

The combination of these sails would enable you to sail in any condition. Of course, the lighter the wind, the larger the overlap. However, if conditions change, you’d have to drop the sail, climb onto the foredeck, bag it, take another bag, hoist it up – and all this while conditions are getting worse, and probably getting dark.

As the wind increases you need to reduce sail area by reducing the LP, that’s the luff perpendicular, and is a percentage of the J dimension. So you make smaller and smaller sails as the wind gets up. A boat will reach hull speed very quickly if you have a number 1 up in 15 knots, but you’d be excessively heeled and struggling to go upwind well. It’s uncomfortable; you’d want a smaller headsail so would opt for a number 2. The boat would be more upright, point better, and be far more comfortable.

A roller headsail has to do everything so you have to maximise its optimal sail area. You’ll find that 135% gives you best performance in light winds, and as the wind increases in the afternoon, you can sail with a smaller area. When it goes to 16, 18 then 20 knots, you can roll it up and you still have an effective sail shape suited to the conditions.

It’s an intermediate sail, but of course, the more you furl the sail and reef it up, the less efficient it is, so it’s all about trying to find that nice mid-point.

Do I need a storm jib?

If you’re going offshore or on an extended passage, you need a storm jib. But these days, how do you deploy it? There are a few options. You can have a jib that wraps around the furled headsail. On a 28ft yacht like Maximus, it’d be around 6m2 but again it’s a compromise. Another option is to rig an inner stay and hoist it up there.

For coastal sailing, dare I say you don’t need a storm jib? But sometimes your insurers will insist on that.

There are certain requirements for storm jibs if you’re doing offshore races, and if passage-making you’d definitely need a storm jib. But 10-20 mile hops between ports? You’re not going to use it, because you’d be picking your weather windows.

What’s a typical cruiser sail wardrobe?

In the old days, you’d have had a mainsail, No1 genoa, No2 genoa, working jib, storm jib and a spinnaker. Nowadays you’d typically have a mainsail, a furling genoa and a cruising chute.

How do cruising chutes compare to spinnakers?

The fundamental difference between a spinnaker and a cruising chute is that the spinnaker is symmetrical; the two leeches are the same length. A cruising chute is asymmetrical; the leading edge, or luff, is longer than the trailing edge (ie the leech).

I made my first cruising chutes in the mid-1980s; back then it was called an MPS – multipurpose sail. They became commonly used in the 1990s.

Unlike a spinnaker, a cruising chute doesn’t need a pole to set it efficiently. This does away with the need for a spinnaker guy, pole hoist and pole downhaul.

With a cruising chute you simply bear away, furl in the genoa, get the cruising chute out of the bag, hoist it, put the sheets on and go sailing. You’d probably deploy it in a snuffer, or sock, blow the tack, pop it down, put it in the bag, put the genoa up and go back upwind.

Can you use a pole on a cruising chute?

Yes, and you’ll have a more projected area. But without one, you just ease the tack line, the sail will lift and project to weather anyway. Ease the sheet to sail downwind. With a pole you’ll be a bit more stable, especially in a seaway, and can charge downwind better, but it’s not essential. After all, a cruising chute is there to make life easy so why complicate it?

What’s the cruising chute wind range?

Cruising chutes are optimised for a 140°-150° apparent wind angle. That’s when they’re at their most comfortable. Any lower, and the sail is wobbly. Anything higher, and you’re on your ear and a bit hectic. But it’s all about wind speed and sea state. If it’s blowing 20 knots and you’ve got a 1.2m Solent chop, you don’t want to put up a cruising

chute. On a 60° reach you’d break the sail and break yourself. But if it’s nice, flat water, 5 knots and you wanted a nice reach, you could easily do 70° or 85°. It would be a flat sail; proper champagne sailing – but as the sea state or wind increases you need to bear away.

Which cloths will be used for the PBO Project Boat sails?

For the PBO Project Boat, a Maxi 84, the mainsail will be crosscut woven polyester, and for the headsail we’re using a hybrid woven sailcloth that’s polyester and Vectran [a manufactured fibre spun from a liquid-crystal polymer]. These unique properties enable us to cut in both radial and cross-cut sections (see below).

What’s unique about Bainbridge’s Vectran cloth, HSXV, developed five years ago, is that the Vectran can be used in both directions of the sail cloth. This gives us a nice matrix grid which reduces stretch and adds longevity and shape-holding to the material.

The Maxi 84 has a radial design headsail and crosscut mainsail. Credit: David Harding

We can cut the cloth in two directions – either crosscut or radial cut. We’ve chosen a radial design for the headsail and a crosscut for the mainsail, both using 6oz cloth.

What sailcloth is good for a cruising chute?

For Maximus’s cruising chute we’ve chosen a radial construction. It performs so much better. We’ve opted for blue and white – PBO’s colours – and an asymmetric colour scheme so you always know what’s the front and the back. They don’t work well if you put them up back to front, but it does happen!

Our BI-70 is a multipurpose spinnaker nylon, which is a high-tenacity with good stretch and very good tear strengths. It’s 1.5oz, 65gsm, and will set in 3/4/5 knots of breeze but you can set in 10-15 knots. You can choose a lighter weight, but this ticks all the boxes. For short-handed or family cruising it will fine.

What is the cheapest sailcloth?

Your least expensive sailcloth is crosscut woven polyester. You’ll get a sail that will do everything you want it to do, it will last a lifetime, and I mean it. Woven polyester sailcloth is so tough these days, but it’s the sail shape in 15 years that will be appalling. Crosscut polyester is durable, relatively cheap, long-lasting and you’ll be able to abuse it like you wouldn’t any other type of material

As it’s a woven cloth, however, so over time the tightness of the weave will loosen up. At the time it was made it would have been optimum for your boat, but over time it will get fuller and deeper and won’t perform as it did when brand new. Will it make the boat go forward? Yes. Can you use it in 5 and 20 knots? Yes. But 20-knot performance will be terrible!

Your next choice, to maintain the weave, is a hybrid woven then you’re looking at cruising laminates. I started making these back in the 1990s. It’s a similar process to building a GRP boat – you add layers and end up with a hull shape. With sails, you have various scrims, made up of different types of yarn and glue them all together. The two outer laminates are encapsulated in woven polyester. There are lots of varieties including Kevlar, carbon, Dyneema, and the bigger the boat, the bigger the loads, so the more exotic the material you use in the laminate.

The downside of laminates is that they’ll let go at some stage. A woven cloth will never let go. It’ll lose its shape but you don’t get catastrophic failure.

How much do new sails cost?

The cost of sails varies considerably depending on the sailcloth, cut, size of boat and who’s undertaking the work. For example, a 15m2 woven polyester mainsail might cost £1,250 for a 28ft Maxi 84 cruising yacht, whereas a membrane sail could cost £3,275.

How long will a laminate sail last?

Eight to ten years for a cruising laminate would be good. Three to five years is average, but the thing about laminate is that the shape will be consistent for the lifetime of the sailcloth. That’s the trade-off: durability over performance, but when spending a lot of money on sails, it’s important to look at the lifetime cost, not just the initial outlay.

What should you do with the sails on a secondhand boat?

If you’re buying a second-hand boat, take the sails to your local sailmaker and ask for their opinion. Sailmakers are honest. They want you to come back and use their services every year; laundering, stitching, maintaining batten pockets, etc. No sailmaker is in it for the quick buck. Most people will take six months or longer to progress with a quote. Choose the right cloth, and the right sailmaker for you.