After a storm leaves our Maxi 84 headsail in tatters, we visit Bainbridge HQ to watch the new sails being designed and cut

During the survey of our Maxi 84, the PBO Project Boat Maximus, we were warned by a marine surveyor that there was only so much he could tell us about the sails.

Marine surveyor Ben Sutcliffe-Davies inspects the sails of the PBO Project Boat

“To see how good a sail is, you really need to take the boat sailing,” said Ben Sutcliffe-Davies.

Maximus had been laid up in a boatyard for two years, and when Ben pulled out the genoa from a locker full of leaves and rainwater, he gave it a good scratch.

“It’s got that nice little noise to it when you scrape it with your nails,” he said. “However, the UV strip is completely worn and faded and starting to break down.”

Sail in tatters

Due to very light winds, however, we had little opportunity to test the sails on our shakedown voyage from Chichester to Poole. Unfortunately, the high winds came later – when Maximus was moored at her new home in Cobb’s Quay Marina. One morning after a storm I returned to the boat to find the UV strip in tatters. When I unfurled the headsail to check for further damage I was dismayed to see it was full of holes and tears.

We returned to Cobbs Quay marina after a storm to find our sail in tatters

Paul Lees of Crusader Sails kindly helped me free the halyard wrap and get it down. The genoa was destroyed, but when he checked out the mainsail he concluded that wouldn’t last much longer either.

“This is on its last legs,” he said. “See how it’s coming apart here. It’s ready to go. If you spent any money on these sails it would be good money after bad.”

Paul Lees of Crusader Sails takes a look at Maximus’s genoa

I emptied the lockers, hoping to find the storm jib so we could still go sailing, but this turned out to be in even poorer condition, with rusty, redundant hanks.

We found this rusty sail in the locker but the headsail now had a furling system rather than hanks

While it is possible to sew a sleeve onto a hanked-on sail, so it can be fed into a furler, it wasn’t worth it on this occasion.

Measuring up

I called Bainbridge International. Founded in 1917, the company is one of the oldest sailcloth manufacturers in the world. If anyone could give me advice on new sails, it was them. Initially I spoke to Mike Cole, and explained the situation.

“It sounds like the UV has got to the polyester,” he said. “Eventually it goes chalky, and you can damage the fabric simply by scratching it. The edges get worn and ripped as the fibres degrade.”

Bainbridge offered to supply new sailcloth, to be made into sails by Southampton-based loft, T Sails. The first stage, however, was measuring up, a job tasked to Bainbridge technical manager, and former sailmaker, Daryl Morgan.

Daryl Morgan of Bainbridge International measures Maximus for new sails

Daryl had been watching the weather keenly, and wasn’t too impressed with the wind when he arrived at Cobb’s Quay this summer. I soon understood why, when watching him winch a swaying tape up the mast on the main halyard. However, having been in the job for over 30 years, he wasn’t phased, and managed to go away with some accurate measurements of the P (mast) and E (boom) dimensions, among others.

Next, I visited Bainbridge HQ in Hampshire to watch the sails being designed. Not only was I getting a mainsail and headsail, but I’d opted for a cruising chute too.

Design in progress

“Sails are the most important investment you can make on your boat,” said Daryl, as he booted up his computer and showed me some impressive 3D illustrations of Maximus. “They’re not expensive when you consider what you get out of a sail. If, for example, you spend £5,000 on some sails for a 35ft yacht, in 10-15 years time you still have those sails. If you spend £2,000 on the latest gizmo that goes bleep, it’ll be out-of-date as soon as it’s out of the box. That will never happen with sails. Every time you pull them out they’ll make the boat go forward. They’re worth the extra cash.”

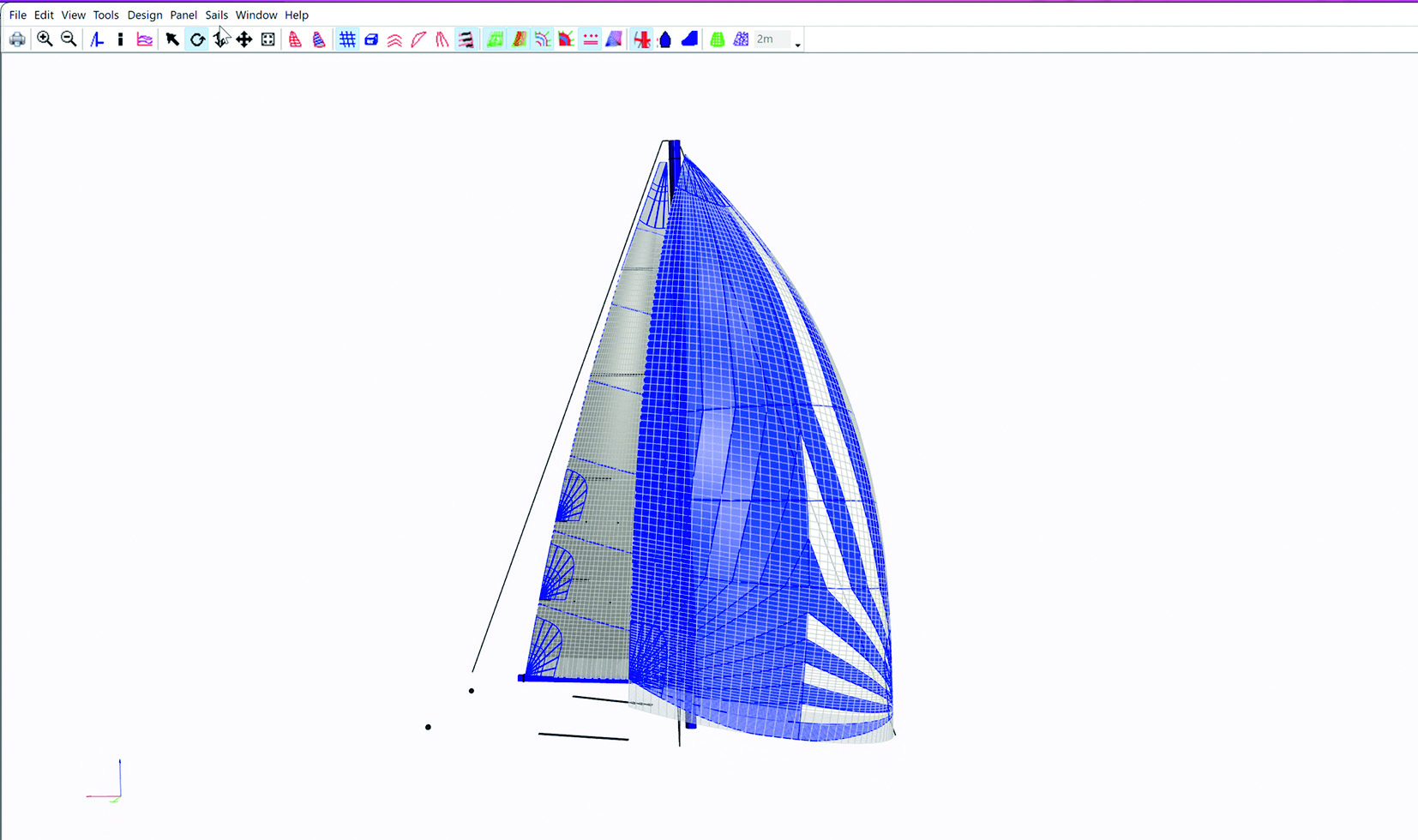

A computer simulated illustration of the new sail plan by Bainbridge International

It was impressive to watch Maximus’s sails come to life before our very eyes as Daryl sheeted them in virtually, eased them off, and simultaneously flew the mainsail, the genoa and a smart looking cruising chute. What was more exciting, was that the sails he’d designed were grey! That would be a first for any boat I’d sailed on.

There’s no material advantage to having grey sails over white. In fact, they’re slightly more expensive, as they need to be dyed, but racing trends often feed down to cruisers, and grey sails are becoming increasingly popular. It would be nice to try something new.

Cutting table

Outside Daryl’s office was the sail-cutting machine itself, a huge table covered in white cloth, which was being trimmed to shape by a computer-guided blade.

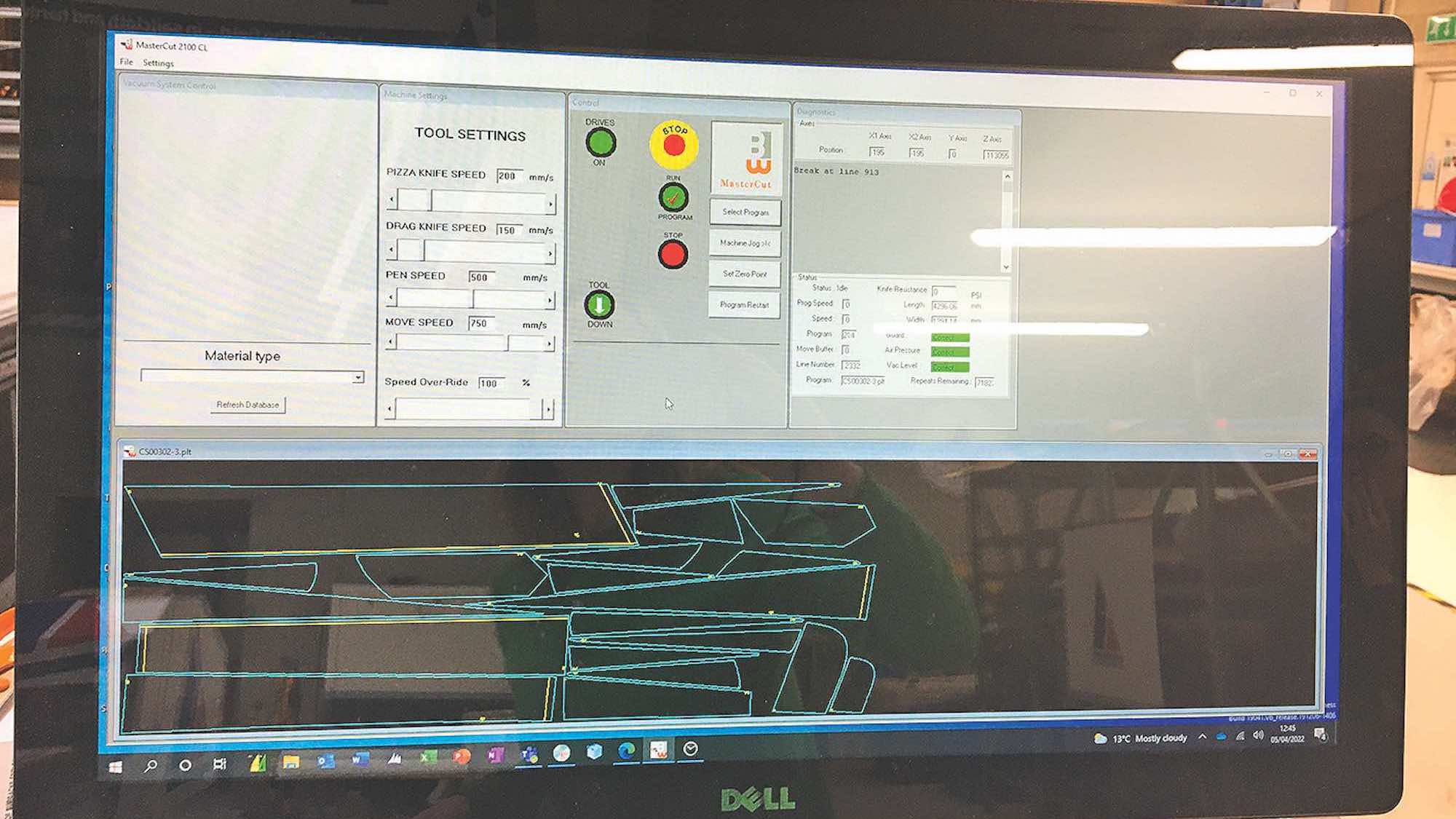

The sail panels are nested together using a computer programme, and the virtual co-ordinates are sent to the cutting machine, which is accurate to less than a hair’s width.

The process was supervised by technician, Ana, who occasionally stopped the machine to climb onto the table and adjust the position of the cloth. It was hypnotic to watch, but noisy because of the vacuum sucking the cloth onto the table. Given that the process would take several hours, Daryl sent me a time-lapse video of the whole event when it came to cutting the sail for Maximus.

Usually your sailmaker will decide the best cloth for your boat, cruising ground and budget, but it definitely pays to understand where your money goes, and what the pay-off is between performance and durability.

Cutting the cloth – step by step

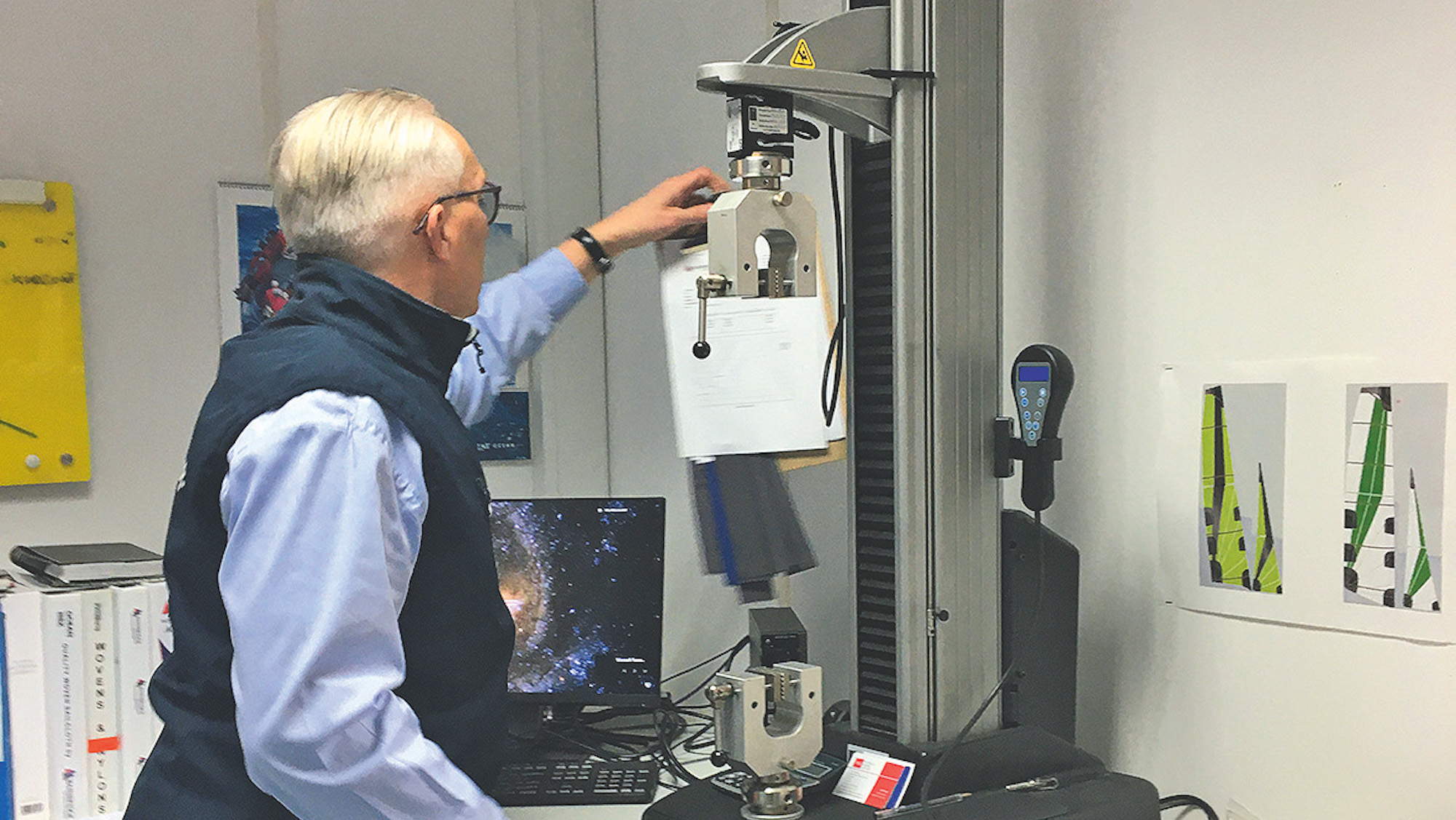

01 The tensile properties of sailcloth are tested: the first, middle and last roll of sailcloth are tested in each batch for warp, fill and bias numbers.

02 Daryl checks the print-out from a sailcloth sample. A selection of all cloth is kept on file. This firm 6oz cloth takes 23.74lb to stretch it just 1%.

03 Daryl begins the sail design process by entering all the boat’s previously measured rig dimensions into a computer programme.

04 Next, he designs a crosscut mainsail, a tri-radial headsail and cruising chute for Maximus using a 3D computer design programme.

05 The sail panels are nested into an efficient pattern on a computer, which sends the co-ordinates to the sail cutting machine.

06 The sail cloth is cut into panels on a 10.6m-long table. This 7oz white Vectran cloth will eventually be a radial headsail for a Contessa 32.

07 A vacuum sucks the cloth down onto the table surface to stop it moving during cutting. The pre-progammed pattern is then cut by laser.

08 For a single sail there might be 60 or more cloth panels woven and cut by Bainbridge. Here Daryl holds one of a table-full of cut panels that have been rolled up ready to go to a sailmaker for stitching and finishing.

As well as manufacturing sailcloth and cutting it ready to send to the sailmaker, Bainbridge also sources the accessories to go with the sail.

01 Luff tape begins life as a 500m roll of 5mm rope and a 500m roll of slit tape. The rope and threads all come from UK manufacturers.

02 The tape and rope are fed through a machine that combines them to make Super Luff. Bainbridge keeps 4km of this on site in their UK warehouse.

03 Fibreglass Aquabatten battens come in sizes ranging in thickness from 6mm to 30mm. They’re tapered, stiff at the back and flexible at the front.

Now that the sails for our Maxi 84 had been designed and cut, the next stage was to send them to sailmaker Tim Scarisbrick at T Sails, who would stitch them together by hand and with sewing machines.