John Willis explains the consequences of cresting a bigger-than-expected wave while helming his 25ft motorboat

Getting to a start line in good order sufficient to achieve the mission can be harder than the mission itself, I’ve always believed. But I didn’t expect to find out how true that was when I sallied forth with crewman George from St Peter Port, veterans of 70 years apiece, though he wears his years more gracefully than I. Our mission was to cross from Guernsey to Plymouth and join the Jester skippers for the 2025 Jester Baltimore Challenge in Island Star, my 18 year old 25ft Beneteau 760 diesel motorboat, to act as unofficial Jester support craft, and taxi for PBO writer and photographer Jake Kavanagh, a task I’d performed the previous two years, crossing the Channel in my 43 year old Channel Island 22.

Beneteau 760: seaworthy craft

Despite the high topsides and extensive glazing of the Beneteau 760, Island Star has proven to be a doughty craft during many trips in a variety of conditions around the Channel Islands over the past 12 months, sometimes in waves over 2m. Indeed, she is a proud holder of the RCD Category B badge, designed to withstand wind speeds of up Force 8 on the Beaufort scale and significant wave heights of up to 4m for voyages as much as 200 miles from shelter.

Island Star is rated RCD Category B and can theoretically cope with wave heights of up to 4m. Credit: John Willis

While both sailing yachts and motorboats can be classified as RCD Category B, the term generally refers to their design capabilities for offshore use, so they are theoretically capable of offshore cruising where occasional adverse weather conditions may be encountered. Category B is unusual in so small a motorboat and suggests that the boat’s scantlings and other key design criteria are sufficient to cope with rough stuff, not that I wish to explore this too deeply in Island Star. Nevertheless, this is all very reassuring.

At this point, I shall issue a spoiler alert – some readers will criticise my decision in what follows, though my crew and I are quite comfortable with it.

Be prepared

Boating comes with risks, as evidenced by the recent unexpected loss overboard of a fellow Jester and good friend, Duncan Lougee, in the Celtic Sea, on a calm day in 2023. In 20,000 or so solo miles, I have learned that the unexpected will occur occasionally, so the sensible skipper minimises risk by thorough preparation and awareness of expected conditions, such as weather, natural hazards and traffic. So it was that crewman George and I set off in good order at 0730, with a forecast of west to west-north-west around 11 knots, expected wave height not exceeding 1m, and made our way on a slack tide down Guernsey’s south coast at a steady 13 knots, tracking south of my old friend Les Hanois Reef, renowned for its moods.

I’d passed along this very route many times before in various conditions – including in my Channel Island 22 – without issue, and today I could see the area was grumpy, though not dangerous, with no excessive wave heights but grumpy all the same; a couple of inshore fishing boats pulled their pots nearby, and we could see happier seas ahead. I throttled back, and we began to push on through, heading north-west of the Hanois lighthouse.

The ‘rogue’ wave encounter happened just off Guernsey’s Hanois lighthouse. Credit: John Willis

Much later, as I wrote this piece, Pete Goss’ April 2024 Yachting Monthly article on rogue waves came to mind. Sailing in balmy weather off the Cornish south coast, he described: “Looking forward a cavernous hole appeared under the bow, and we seemingly plunged off the edge of the world.”

Well, it seems we might have found something similar, if not nearly so dramatic. Cresting a wave that seemed little bigger than the rest, I suddenly saw we were poised over what I can only describe as a hole in front of us. “Hang on tight, George!” I yelled as Island Star seemed to belly flop down with a jarring crash that sent me flying to the floor. George, who had landed back in his seat, took the wheel briefly until I could get back up and take over: we both appeared to be okay, so I began to check this and that before making any decision.

The Nanni 200hp diesel continued to purr, engine readings were normal, there were no unusual noises or vibrations, the auto bilge pump didn’t activate, the big sliding side windows slid smoothly open and closed, suggesting no distortion of the wheelhouse structure, the main and forward bulkheads were fine, and lockers, engine room, shaft gland and bilges were all bone dry. The only breakages seemed to be broken toilet seat hinges, two plastic beakers and the top step down to the fore cabin on which I’d landed heavily, before falling backwards onto the wheelhouse floor. More importantly, the only extra leak was from the top edge of the windscreen, where it had always leaked a little, so I was not concerned about that as it was on my ‘to do mañana’ list.

Crewman George was quite calm and keen to continue, so we decided to carry on to Plymouth at 12 or 13 knots, an easy jog for the Beneteau 760. The wind, now about the same speed, was just ahead of the beam and the Channel became a little lumpy so we took a lot of flying spray, but the brand new autopilot coped just fine, allowing me to relax comfortably with pea and ham soup, followed by homemade scones and coffee, while George rested below, seasick I thought.

Fallout

After six-and-a-half wet, bumpy but uneventful hours, it was good to dock in Plymouth’s Mayflower Marina, assisted by their friendly staff. Naturally, safe in harbour, my self-doubting began, particularly when we discovered that we were both a little battered and bruised, and George now told me he had gone below to rest his jarred back, not because of seasickness. I’d have turned back had I known – but he knew that!

At this point, I discovered the brand new engine room fire extinguisher had slipped from its mounting into the bilge and wedged under the engine. It hadn’t gone off, presumably as it was undamaged, and the engine room is well ventilated with no excessive heat sources; Island Star also carries two 50+ second Fire Safety Sticks as backups, which can be used through a small engine room inspection hatch.

Over a glass of hair restorer at Jolly Jack’s Bistro that evening, we reviewed the day, and both concluded we were glad we continued, and it wasn’t the alcohol talking. True, we’d both suffered a little bruising, and I’d cracked open my shin, but we were cheerful, even elated.

All’s not well

But, the next day, the engine wouldn’t restart, and my guess was that water from the leaking windscreen had got into the ignition switch. While I have reasonable mechanical theory, I lack practical experience on marine diesels, but thankfully, the Gods delivered salvation in the beefy form of John Williams, an ex-Army marine engineer seemingly happy to help a fellow veteran.

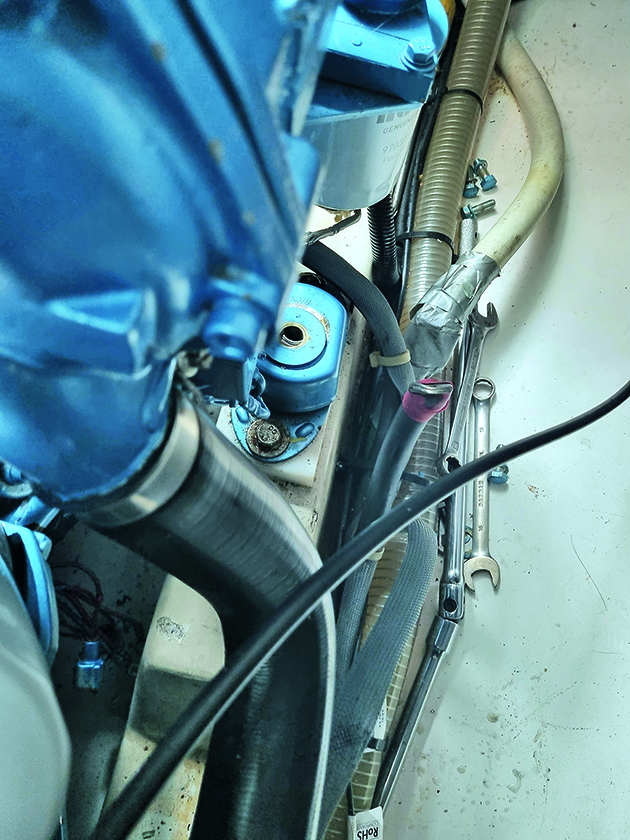

The broken engine mount on the Beneteau 760. Credit: John Willis

It quickly became clear my guess was way out, and I began to fear we’d not make the start line, but that was to underestimate engineer John, who spent several hours over two days head down over the engine, removing and straightening a bent engine mount bracket and replacing the associated bolt, replacing the cracked starter motor and retrieving the undamaged fire extinguisher.

As John worked, I fixed the windscreen with transparent Gorilla tape, something I never go to sea without – it passed the leak test too! As in the previous two years, our self-appointed unofficial Jester role was to give any assistance we could to skippers and to provide a platform for photographs of the start.

On the day of the start, we helped Andy Merrett and his wife turn his Rival 32 round to ease his departure, and I presented French skipper and friend Christian Gallot with a bottle of Jester labelled wine – Christian had completely outsailed us to be first over the line in the rough 2021 Jester Azores Challenge. I set off with PBO’s Jake Kavanagh and Bernie Branfield, one of three members of the Jester Helm who oversee the Jester Challenges.

Engine mount with bent bracket removed. Credit: John Willis

Bernie took the wheel briefly, while I rechecked the engine room, but everything seemed fine, so I opened the throttle to get on parade with the Challenger fleet. Hamish Southby Tailyour, the Challenge starter, was already anchored in his Moody 33, Equinox, at the west end of the start line running from Plymouth Breakwater lighthouse, like his father, Ewen, before him. Also like his father, he carried a shotgun loaded with talcum powder to be fired at exactly 1200 to signal the Baltimore Challenge start.

Boat spotting on a Beneteau 760

I never thought that my first-ever book purchase, a much-thumbed copy of the 1972 Bristow’s Book of Yachts, would ever have any practical value, but I was wrong, for it triggered a lifelong obsession with boat spotting – like a train spotter but probably sadder. As most Jesters are in older boats from the 1970s and 1980s, I generally have little difficulty in identifying them so, armed with the start list, I was able to identify individual Jester boats.

Jake, standing in Island Star’s broad well-protected cockpit, would shout instructions like – “John, I want the little Corribee with junk rig next please…” “Roger, I see her, Jake,” and off we would go in my Beneteau 760 like a happy sheepdog. I will confess that Jake was a disruptive influence, as he had me in stitches half the time, being a natural and most amusing raconteur, and we were a very merry crew as we went about our business.

As the one-minute warning came over VHF Ch72, the Jester skippers converged on the start line, and when Hamish blasted a cloud of talcum skywards, they tightened sheets and headed out to do battle with a light contrary westerly wind, prelude to a very tiring long slog to Bishop’s Rock. We held station alongside the fleet for a while, so Jake could take some fleet photos, as Will Robinson’s beautifully sailed Achilles 24 took an early lead just ahead of Pete Matthews’ fast-closing Contessa 32.

Checking the engine during sea trails off Plymouth. Credit: John Willis

Of course, the Jester Challenge is emphatically not a race, but put 35 skippers on a start line and what have you got? Each year many more enter a Jester Challenge than actually make the start, and out of those that do, some naturally retire. This time, about 43% did so, mainly because of light headwinds and time constraints, but that didn’t prevent the 2025 Jester Baltimore Challenge from being a resounding success.

In my humble opinion, it is the sensible skipper who doesn’t go, or turns back before or after the start, if he or she feels overwhelmed for whatever reason. It is good seamanship and no cause for shame and I salute those who fought so hard to come from afar, like John Moody in his Mirage 29 based on the River Blackwater, who battled adverse winds for days before sensibly calling it a day and pausing in the Isle of Wight for a break with his wife, before heading for home all the while fixing this and that on his boat. I’ll add that although the challenge is intended for boats smaller than 30ft, nearly a third were a little longer, but so what? It’s the spirit that’s important, and this event demonstrated plenty of that.

Island Star’s organised helm. Credit: John Willis

I have modified Island Star’s wheelhouse layout to better suit my requirements and think she is ideal for her Jester support roles, certainly better than little round bilged Water Rat, my Channel Island 22, as her broad semi-displacement V-hull form and well protected cockpit provide a more stable and better protected base, and her powerful engine enabled us to run around the fleet as required. To be honest, and I shall whisper this, I think she demonstrated she has Jester spirit too; tough, not in the first flush of youth, unassuming, doesn’t stand out in the crowd, quietly capable for what she is. Just like a Jester; someone you probably wouldn’t invite to your party, but who is good in a blow with a taste for adventure. “Know what, John,” said one Jester with a twinkle in his eye, “you should put a pillow tank on board Island Star and come with us.” Now there’s an idea…

Flying solo

Back at base, crewman George had to redeploy for a home medical emergency, so two days after the Jesters left for Baltimore, I set course alone for Les Hanois, 85 or so miles away, at 14 knots on a calm day with very light winds. I deliberately chose such a day, just in case, and with strong winds later in the week it was now or never if I wasn’t to be stuck in Plymouth for a while.

The Channel was busy with shipping and dolphins too, and I must have seen 50 of them, one pod easily overtaking me at perhaps 20 knots. Wonderful! As I closed the Hanois Reef around midday, I passed over the scene of our crash on the outward leg, at roughly the same state of tide, albeit with 5 knots less wind from much the same direction, yet there were just a few ripples and whorls, as if it was saying, “Surprise!! But don’t be fooled – we’re still here, you know.”

Homeward bound and passing the Plymouth breakwater. Credit: John Willis

Looking back, would I have done the same thing? Absolutely. I believe we encountered a rare combination of circumstances, which the Beneateau 760 actually coped with very well, and we did as full an appreciation of our circumstances as we could reasonably do at the time, before deciding to continue. The incident has increased my faith in my little Beneateau 760, though in future, I will consider routing slightly to the south if the seas are grumpy there, more in deference to ageing bones than absolute necessity, and will see about installing additional handholds – and perhaps a bean bag on the wheelhouse floor.

Rogue waves and God willing, my Beneateau 760 and I will be on the start line next year for the Jester Newport Challenge, the big one.

Island Star was subsequently checked by a surveyor, who confirmed our on-the-spot assessment that her hull, prop, shaft and rudder are all undamaged. The Beneateau 760 is a tough little ship!

Replacing your boat’s engine mounts

Marine engine mounts are designed to isolate engine vibration noise from the boat’s structure. They’re susceptible to diesel and water…

Boat engine mount replacement: step by step guide

Mike Reynolds shares the lessons he learned about undertaking a boat engine mount replacement

10 ways to save fuel when motoring: Essential tips for engine care, hull trim and propeller pitch

As costs rise, Jake Kavanagh looks at the simple ways boaters can use less fuel and energy when motoring

Guide to buying your first motorboat

There are many reasons why people want to buy a motorboat – the recent Covid-19 pandemic (and a generally unstable…

Want to read more articles like The Beneteau 760 vs a rogue wave?

A subscription to Practical Boat Owner magazine costs around 40% less than the cover price.

Print and digital editions are available through Magazines Direct – where you can also find the latest deals.

PBO is packed with information to help you get the most from boat ownership – whether sail or power.

-

-

-

- Take your DIY skills to the next level with trusted advice on boat maintenance and repairs

- Impartial, in-depth gear reviews

- Practical cruising tips for making the most of your time afloat

-

-

Follow us on Facebook, Instagram, TikTok and Twitter