Max Liberson sails to the Caribbean aboard project boat Lunatoo, a Seadog 30 with added bowsprit that was made sea ready for less than £4,800

The wind was coming on like my brother Alex had warned me it would, as I approached the north side of Carriacou island, one of the Windward Islands of the Caribbean, but the current was pushing us steadily south. I’d held onto the twin running sails for too long really, because they were comfortable, but when I wanted to broad reach across just using a reefed mizzen and well rolled up genoa I realised my mistake.

Going around the south side would be quicker, but I would need to concentrate and actually steer the boat rather than leaving it all to the venerable and ancient Hydrovane. This was a problem because at the end of a 33-day single-handed passage from the Canaries I was a sleep deprived mess and liable to drift off to the land of nod.

pontoon party at Southdown Marina the day before departure. Credit: Max Liberson

Still, with the dawn only a short time away I reckoned I was in with a good chance of not piling up on one of the many small islands and reefs scattered around so we (that’s me and my wonderful Sea Dog 30 ketch called Lunatoo) went for it.

Along with the freshening wind came squalls of heavy rain, so I closed up the cockpit tent and stayed dry. We thundered on, and I found a course that safely took me between Saline Island to starboard and Frigate Island to port.

My mind drifted to visiting Saline with my fiancée, Eva, who became my wife 10 years before. I fell asleep, I woke myself up and gave myself a slap. “Concentrate fool,” I yelled, so I thought about Frigate Island and I remembered landing on there and finding big tortoises, and a goat, nothing else, my mind was wandering again, so I administered another slap.

Stowaway

The daylight was well past the making out a grey goose stage, when movement from the bow area caught my eye; I’d forgotten about the stowaway. A big, white, bulky form with a long orange bill shuffled on awkward webbed feet to the rail and threw itself into the sea. I’d discovered the tropic bird passenger when I went to take in the twin running sails some hours earlier. It was not happy about my presence and barely tolerated me edging past it so I could change the sails. God only knew what it would make of a tack.

Anyway, once we’d settled down and I’d switched off the spreader light it grumpily took itself off to the bows. Then I forgot completely about it until it made its exit. No time to take photos, or to even bid farewell.

Safely past the islands, it was easy to identify Mushroom Island because it looks like a giant rocky mushroom and the dangerous reef that lies between that and Southwest Point had its presence betrayed by the sea breaking white over it.

Mushroom Rock. Credit: Max Liberson

We crashed on past and I brought us closer to the wind. Lunatoo was still making good usable speed but we had dropped to 4 knots, a reefed main would have helped but we were so close to Tyrrel Bay I wasn’t going to bother, and then I saw the masts and boats and a tug grounded on the rocks and I knew I was near my spiritual home, the wonderful Carriacou Island, and I had to pinch myself because it was almost too dreamlike to be real.

In short order I’d rolled away the genoa, and fired up the Perkins 4108 to let the oil pressure build to 4.5bar before putting it into gear. Lunatoo, being a good mannered boat, lay with her bow pointing at the wind while we went through this ritual.

Then we were bashing our way through the short chop into the anchorage. Ashore, I could already see the scars that Hurricane Beryl had recently left, and even some of the boats I was passing had masts missing and dreadful damage. These were the lucky ones – plenty of others hadn’t made it out of the mangroves when Beryl struck.

Hurricane Beryl destroyed the only house on Saline Island. Credit: Max Liberson

I found a space and in 13ft of water dropped the CQR and let out 30m of 8mm chain. I snubbed it – on account of a strong gust of wind we were moving rapidly astern – and then the anchor/anchor types bit and we stopped. I checked the background against nearby yachts: we’d definitely stopped so I let out another 20ft and attached a nylon snubbing rope, walked back to the cockpit and stopped the engine; we had arrived. I had travelled almost 3,000 miles in my restored £1 project boat.

Bargain temptation

Two years earlier my brother, Matt, had to get rid of the Sea Dog 30 ketch so he could take up a position of manager in another boat yard. It was an insurance write off, having suffered a gas explosion, and although he got it free instead of breaking it up, he was having to pay a monthly storage fee to keep it. So, long story short, he sold it to me for £1 and I took over paying the monthly storage fee.

At that point I was already the proud owner of the 1936 gaff cutter Wendy May, and I was staying on her in the nearby Southdown Marina while I worked on completing the 50ft trimaran Trinity.

Max working on the small table he made in the cockpit. Credit: Max Liberson

My wife was stuck in her house in Wolverhampton looking after our dog and her elderly mother. The last thing I needed at that point was yet another boat project. But the Sea Dog has sweet lines, and character, and I fell to temptation.

We had something of an Indian summer that September a couple of years ago. My friend Will from Downderry came over to help me carry the masts over to the Sea Dog once she’d been lifted out of the water. He declared I was the luckiest man afloat to have scored such a boat for £1. I didn’t feel very lucky for long. A series of personal tragedies struck and in short order my family lost all of our elderly relatives, and my wife lost her lovely mother. Obviously over that period I had to be by her side and all boat projects took a back seat.

On the move

In the new year, I made it back to Southdown Marina in Millbrook and because it was getting very cold, moved on board Lunatoo as I’d fitted a solid fuel heater I’d found under my brother’s bench.

I had to resuscitate it and give it a new glass and stainless steel chimney but it was free. That’s when the yard bosses told me they needed the space that Lunatoo was in. Fortunately, the team at Southdown said I could use one of the empty slips for a few weeks.

In short order I made the boat watertight, had the engine running, sorted out the rigging and with the help of the yard manager Dan and his telehandler raised the masts. A coat of antifoul and we were sort of ready for launch.

Lunatoo was hoisted into the water, motored over a few hundred yards to the slip and tied up. Over the next few days I finished getting her seaworthy and then, on one of those few perfect late winter days, I took cruising legend Nick Skeates and my old friend Will for a sail. I was flabbergasted to discover that Lunatoo sailed far better than I expected – after all she had a long keel as well as two bilge keel/twin keel that doubled as water tanks, she displaced 6 tonnes and only drew 1m.

As if that wasn’t enough the mizzen and the main had been made by Crusader and were dated 1996! Crusader is renowned for quality sails, but 30 years is a long time for a sail to keep its shape, and they were on board when the poor boat was blown up for goodness sake!

Fleet reduction

Anyway, without a job and existing on a UK basic pension I could not afford to have two boats so one had to go. I decided to find a new custodian for Wendy May and she was snapped up by a young boatbuilder.

I decided I wanted to sail once more to Carriacou, to scatter my father and my stepmother’s ashes there. They had such a good time sailing among those islands in the past and I was sure they’d have approved of such an adventure.

I also wanted to see how the people I’d met and grown to love had fared after the dreadful hurricane they had just experienced. And also I wanted to demonstrate that boats such as Lunatoo can be bought for a pittance, restored to seaworthy condition and used to travel pretty much anywhere the heart desired.

My first solo crossing of the Atlantic, from Carriacou to the UK, was aboard a 38ft ferrocement schooner. The engine was not working, I had no self-steering gear, and the boat was a bit short of sail area. The 4,200 miles took me 58 days to cover and I arrived home in July 2011 exhausted, sleep-deprived and thin after an average daily mileage of 72.4 and dismal speed of 3 knots.

Max found a waterproof beanbag made an excellent watch chair. Credit: Max Liberson

Luck was a big part of a successful conclusion to that trip, and I learned that Gloria was too big at 16 tons for me to handle alone. The schooner rig with no furling gear took a lot of managing, sails had to be changed or handed. My record for sail changes was 18 in one day!

My second Atlantic circuit, from 2014-15, was aboard a Trapper 500 with a transom-hung rudder that I made. This was faster but the 27ft 4in boat was a little on the light side and was knocked down easily by big waves and not very comfortable.

The Sea Dog was a happy medium – a 30ft ketch with some sweet curves and quite a modest sail area.

Under the cockpit sole lurks a venerable Perkins 4108, that produces 38hp – far more than needed. I added a short bowsprit to move the forestay forward by 4ft and Hydrovane self-steering that I’d bought incomplete from a boat jumble, then put some extra batteries and some solar power on her, replaced the gas cooker with a couple of primus stoves bought from ebay and went sailing.

Most of the money I had to spend was on getting things like the sprayhood, cockpit tent and sail covers made.

In addition to getting Lunatoo shipshape I worked on my fitness, riding my mountain bike eight miles over the hills to a beach near Down Derry for a swim most days. I also added in four sets of 50 push-ups throughout the day.

Between that and eating well, I started to feel a lot younger than the 66 summers that I have seen.

Third circuit

I left in September 2024. Lunatoo hosted a pontoon party at Southdown Marina the day before and some of our close friends, including Nick, came to wish us bon voyage. Firmly refusing the tempting invitation of a rum testing session, I woke up the next morning without a hangover at 04.30. Top of the tide was at 05.00 and three friends emerged to help me out of the berth.

Once in Plymouth Sound I hoisted sail, got the Hydrovane set up and then took in the mizzen and away we went. The wind rose to about 18 knots from north-easterly to east and we fair flew along. The new bowsprit is worth its weight in gold and Lunatoo balances out beautifully. The wind was a tad chilly so I refitted the cockpit tent and made the cockpit snug again.

Max recommends the Garmin inReach compact satellite communicator. Credit: Max Liberson

Sadly at 0200 the wind dropped off and the Hydrovane could no longer keep us on course once our speed dropped below 2 knots, and so I started the engine and began to hand steer.

We were then 5 miles east of the Ushant separation zones. My handheld radio also has AIS on it and did a sterling job of warning me of traffic I had to watch out for.

Troubleshooting

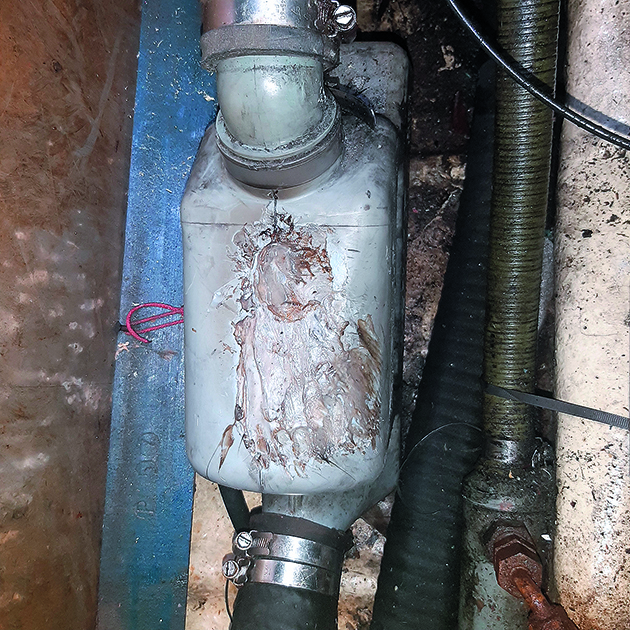

With the daylight, the first real problem showed itself. An engine bay inspection revealed the plastic exhaust collector box had split on the seam and exhaust gas with a fine mist of sea water were making a right mess.

We carried on and worked our way into Port du Stiff, Ushant. Keeping our revs down meant we were able to time our arrival to low water and the end of the hard running tides which gave us an added safety margin.

Plastic water bottle patch after an engine bay inspection revealed the exhaust collector box had split on the seam. Credit: Max Liberson

The chartplotter showed us the way in but the most useful tool was our lovely steering compass. I’ve refurbished this instrument and it has a good light to illuminate it. It’s far easier to use than any electrical equipment in conditions when you must be on the helm and watching out for anything emerging from the harbour that you cannot see, but know is there.

Once in, I found a free visitors’ buoy and moored up. The next morning I used a low flame blow torch to melt plastic from a cut up water bottle and welded a plastic patch onto the collector box.

Biscay curve balls

Then I continued south across Biscay.

As normal, Biscay threw a few curve balls. A thin-wired halyard wrapped around a sail slider and jammed the main up when I tried to reef, and during the blackness of nights I had a visit from a large pod of pilot whales – boy did that get my ticker beating!

After catching my breath in Cedeira, Spain, for a couple of days, I meandered along the Portuguese coast stopping at Portimão, then Figueira da Foz before sailing to La Gomera in the Canaries, ready for the Atlantic crossing.

Bread that Max made while sailing the Atlantic circuit, ‘it looks funny but tastes great’. Credit: Max Liberson

I left Europe on 18 December and sailed in the general direction of Venus until I arrived in Carriacou’s Tyrell Bay, some 34 days later on 21 January. I’d left a bit early so the trade winds had not really established. I also had the problem that I broke a couple of toes on a bronze winch while in a hurry to get back into the cockpit. It was incredibly painful and I couldn’t put any weight on my foot for a while, so I left the big reef in the main and was a bit slower than I could have been. But I still found the crossing enjoyable.

Sail in company

My injury mended and Lunatoo and I had arrived in Carriacou in good shape, although the old mainsail now seemed alarmingly transparent viewed in the tropical sun.

The local sail maker, Jacqueline, took it in for some repairs and said it would probably last the trip back, but she had an almost unused mizzen sail from a 50ft yacht that she could alter to fit so I had a spare. I agreed to this, and a couple of weeks later stowed the sail below as a ‘just in case’.

Max following friend Pete into a reef-cluttered bay. Credit: Max Liberson

I then met up with my old friend Pete Evans and we spent a few weeks sailing in company, to places around Carriacou and Grenada that few yachts venture. His yacht Rocinante drew 5ft so I was hardly nervous at all about following him into reef-cluttered bays on account of if he could float, I certainly could.

Unfortunately, unlike my last Caribbean adventures, my wife Eva could not join me because she was busy buying a house in Cornwall and moving into it.

After an almost ideal few months it was time to do the homeward trip. This time I planned a slightly different route, skirting the areas where on both previous passages I’d been well and truly clobbered by bad weather. I also left the Caribbean two weeks earlier, gambling that with water temperatures being slightly higher the season for calm weather crossing of the Atlantic might begin a couple of weeks sooner.

Pete’s Pacific Seacraft 35 survived Hurricane Beryl. Credit: Max Liberson

The Sea Dog was so comfortable and the work of keeping her sailing so relatively easy that I did not feel the need to stop at the Azores and pressed on to finally drop my hook in the Cornish mud of Barnes Pool in Plymouth Sound, 47 days after departure.

The cost of my trip from Cornwall to the Caribbean is easy to quantify, tallying up as £4,783.50 in parts for getting Lunatoo seaworthy, but the value of such moments as ghosting under twin headsails down the track illuminated by moonlight over a flat smooth sea on a vessel I saved from becoming landfill are beyond price, and I already have a whole stack of wonderful new memories.

Single-hander knowledge

- Don’t ever listen to the nay sayers: most have failed or were not brave enough to do the things they wanted to do, and they don’t like the idea of you succeeding.

- A boat does not have to be expensive to be seaworthy, but it does have to be strong. It’s better to have a simple and strong boat than something that is complicated and liable to break.

- The great yacht designer Uffa Fox once declared that “weight was only useful in steam rollers”. He was undoubtedly a genius at making fast sailing craft, but for a cruising yacht a bit of weight can be useful in damping out the motion. If a yacht is comfortable, it might be a bit slower, but the sailing might well be far more enjoyable.

- You must be able to reef and change sails easily; if it’s too hard you’ll wear yourself out and not be able to keep the yacht going at an optimum speed.

- Get ocean fit to meet the physical demands of single-handed sailing, through exercise. And frequent cold water swimming immersions will allow your body to get used to the sudden drop in temperature so you don’t involuntarily gasp when you first enter the water – useful if you need to go into the sea for any reason.

- Learn first aid. When I broke a couple of toes on a bronze winch, they stuck out and I kept catching them and almost fainting. So, I decided to wrap a bit of kitchen paper around it and drip super glue over the paper to make a cast. Sadly, the paper, glue and my warm foot caused a ‘thermal runaway’ and cooked my toes! At least the now solid ‘cast’ immobilised my toes but some days later it fell off to reveal two very large blisters and my already swollen foot got bigger. The pain stopped me from sleeping, so I lanced the blisters with a razor blade. To avoid infection, I smothered the mess with good quality honey, then drank some rum for the pain. Eventually my foot healed, and I now only have some scars on my toes to remind me of the law of unintended consequences.

- To get my mind in good shape, during the trip I worked on my celestial navigation using a good sextant, the two volumes of air tables and an Admiralty Nautical Almanac. My goal was to dust off my skills of getting a noon fix and unveil the mysteries of getting a proper position.

- I may have been a trifle cavalier by not buying a liferaft to take with me, but so far (touching wood) I have got away with it.

Expert comment

Nick Skeates. Credit: Lizzie Bowen

Nick Skeates, cruising doyen, designer and builder of the boat Wylo II, and who was presented with the Ocean Cruising Club’s Lifetime Award in 2020, comments: Like Max, I was very surprised at how well the Sea Dog sailed in light weather when we went for the first test sail. I think Reg Freeman did a very good job designing her.

I enjoyed reading Max’s ‘Lessons learned’. He rightfully highlights the single-hander’s dilemma when closing the land. This is often the most dangerous part of any voyage, due to not only the presence of inconvenient rocks and reefs but also other vessels. The main trouble is lack of sleep. The answer is, of course, having crew, but failing that you must manage your sleep as best you can.

Giving a blown-up Seadog a new lease of life

Max Liberson adopts a down at heel Seadog – blown up in a gas explosion – and decides to give…

Sailing solo: how to go from crewed to single-handed

Round the world sailor Ian Herbert-Jones shares valuable advice on how to transition from crewed to single-handed sailing

Your ultimate checklist to prepare your yacht’s systems for an ocean crossing

Completing an ocean crossing, such as the traditional transatlantic passage from the Canaries to the Caribbean, is a bucket list…

Barry Perrins: ‘I bought the boat and lived the dream’

After nine years of circumnavigating the globe, 'old Seadog' Barry Perrins talks to Laura Hodgetts about seamanship, the realities of…

Want to read more articles like 3,000 miles solo in a £1 boat: lessons learned from an Atlantic Circuit?

A subscription to Practical Boat Owner magazine costs around 40% less than the cover price.

Print and digital editions are available through Magazines Direct – where you can also find the latest deals.

PBO is packed with information to help you get the most from boat ownership – whether sail or power.

-

-

-

- Take your DIY skills to the next level with trusted advice on boat maintenance and repairs

- Impartial, in-depth gear reviews

- Practical cruising tips for making the most of your time afloat

-

-

Follow us on Facebook, Instagram, TikTok and Twitter