Will Spencer explains how to prepare your boat for sailing offshore, and the regular checks all sailors should make before an ocean crossing.

Completing an ocean crossing, such as the traditional transatlantic passage from the Canaries to the Caribbean, is a bucket list item for many. It’s both a fantastic experience and a huge achievement for the amateur sailor, the ‘Everest’ of the recreational sailing world.

Preparing your yacht to go offshore is more than a list of jobs; it’s a mindset shift.

For those readers who aren’t venturing into the middle of the ocean just yet, many of these checks are still prudent.

Offshore sailing demands more from your systems, more foresight in your planning, more consideration of redundancy and a greater level of self-sufficiency when you can’t just call for backup. But equally, worrying about every possibility means you’d never actually leave.

Learning how to maintain your boat’s systems, like the engine, is prudent for all sailors. Photo: Ali Wood

As an ARC safety inspector, I’ve seen everything from last-minute panics, comprehensive preparations and skippers saying “they’ll be ready next year”. Finding the sweet spot can be tricky; this is what we aim for in every bluewater project: balancing the budget, the risk and the timeframe.

In this article, I’ll walk through the core elements of offshore systems preparation: assessing what you need, setting a realistic budget, scheduling work, building a maintenance plan, and putting together a smart spares list.

Along the way, I’ll share lessons from the boats we’ve worked on and the owners we’ve helped get ocean-ready.

The ultimate goal is to have a safe, fully operational and self-sufficient yacht, ready for the intended passage, being manned by a knowledgeable crew.

What an ocean crossing really demands from your systems

Your goal isn’t perfection. It’s preparation. Know your boat. Know what matters. Fix what needs fixing. Photo: White Dot Sailing.

Offshore or ‘bluewater’ sailing is unrelenting on yachts, even the traditional east to west transatlantic route, with systems being exposed to increased UV, humidity and motion 24 hours a day.

In my experience, I’d estimate that each ocean crossing can be the equivalent of at least two average cruising seasons in the UK.

Systems like battery banks (capacity), autopilots (the extra crewmember) and fridges (operating in much warmer water/air temperatures) may not have been critical in coastal cruising but are often the most heavily relied upon mid-ocean.

Key systems under strain when sailing offshore

Make sure you keep a detailed maintenance log so nothing is missed. Photo: White Dot Sailing.

Rudders and steering systems

Wear in cables, sheaves and bearings is exacerbated by the constant motion of ocean swells, and downwind sailing conditions.

Modern self-aligning bearings supporting balanced rudders should be fresh water rinsed, and the inner bearings removed and inspected from the housing periodically.

Rudders should be moisture tested, drained and dropped with stocks checked for damage and corrosion.

Autopilot

Used far more during offshore passages, under-strength autopilots operating at close to their safe working load for long periods can result in early failure, anywhere from the motor to the quadrant.

This can be exacerbated by an increase in overall weight due to the addition of supplies and equipment.

Poorly trimmed sails can often go unnoticed while on autopilot and lead to increased loads on the whole system, including the rudder.

Power generation

Battery health is critical, and all regeneration must come from onboard sources such as solar, alternators, hydro and diesel generators or wind systems, which need to be robust and integrated well.

Power consumption is often underestimated; regeneration should carry redundancy over multiple systems and be usable at sea and at anchor.

A power audit spreadsheet can be found at my White Dot Sailing website.

Rigging

Ensure sails are properly trimmed; otherwise, it could increase loads on the boat’s systems, including the rudder – especially when using an autopilot. Photo: White Dot Sailing.

Constant and dynamic loads can find weaknesses in any rig quickly. Aged wiring can fail during an ocean crossing, navigation lights will be used 50% of the time (12-hour nights) – so it’s worth upgrading to sealed LED.

Deck lights become a safety priority when working on the foredeck at night.

Lines are susceptible to chafe. If a halyard moves 5mm/sec back and forth over a sheave, on a 20-day ocean crossing, it will have travelled 8.6km or 5.4 miles!

The quadrant on this Moody 46 failed during the Atlantic crossing. Photo: White Dot Sailing.

This Moody 46 steering system had an autopilot pin in the centre of the steering quadrant. The pin was improved as part of the assessment and refit period.

During the Atlantic ocean crossing, the quadrant failed. This was likely due to the increased load brought about by a heavier boat, but could also have been due to sea conditions encountered and a lack of focus on trimming and reefing for a balanced sail plan.

This highlights how improving one part of the system can move the weakest link to another part.

Assessing your yacht for an ocean crossing: what’s ready, what’s not?

This is where preparation starts in earnest. We walk through a boat system by system and ask these fundamental questions:

Is this suitable for constant use in offshore conditions? Will this last for the whole of the intended project? Can I maintain it?

Understanding the system

Navigation lights will be used regularly, so inspect them and consider upgrading to sealed LED lights. Photo: White Dot Sailing.

If you’ve owned the boat for several years, you’ll naturally gravitate to areas you feel comfortable with and touch every day.

Questioning the limits of your knowledge can be essential to successfully assessing each component.

While we encourage owners to work on their own systems as much as possible, this is where surveyors and industry professionals can assist in filling knowledge gaps.

By engaging professionals at the right time, not only can the system be thoroughly checked and worked on, but you can also learn from them while it’s being done.

Also, bear in mind that your insurers may require certain checks by professionals, like rig checks and a recent hull survey.

We’d usually recommend unstepping any mast over five to seven years old (depending on its history); you’ll require a rigger to provide a professional report and manage the unstepping (if required).

Once the rig is on the hard, there’ll be plenty of remedial work you could engage with yourself – replacing electrical wire, changing navigation lights, removing and checking running rigging.

Current system maintenance

Removing and inspecting the exhaust elbow and heat exchanger will determine if maintenance is required. Photo: White Dot Sailing.

Starting from a known point is vital. Is the current system fully functional?

To assess this, it may require disassembly or even some level of destructive testing, but when going offshore, you need to be completely sure.

Engines that operate in the cooler waters and air temperatures of Northern Europe can often show cooling inefficiencies closer to the equator, especially when operated for longer periods.

Removing and inspecting the exhaust elbow and heat exchanger can determine if any maintenance is required.

If all is well, the cost is your labour and some new gaskets. Volvo Penta recommends exhaust elbow inspections every two years on many models. You can get stainless steel upgrades, which would extend these inspections and increase lifespan.

Recondition/replace

The windlass on this Southerly 42 was reconditioned, including a blast and respray, for a third of the price of a new one. Photo: White Dot Sailing.

For those systems that may not be fully functioning when assessed, you must decide whether to repair or replace.

From an economic and environmental standpoint, we always look to recondition systems if they’ve not reached the end of their useful life.

Remember to account for the whole adventure when making your decision; you don’t want to be conducting major upgrades during your time cruising.

With parts diagrams and service kits readily available, making informed decisions early in the refit/preparation phase will save you time and money in the long term.

Anchor windlasses are a good example; often neglected and constantly operated in a harsh environment, they become very beneficial when cruising.

We refurbished a Lewmar windlass on a Southerly 42 recently, for a third of the price of a new system, including a blast, respray and new warning stickers

Servicing

Engine oil changes might be more frequent, so know the specified intervals for maintaining your systems. Photo: Graham Snook/Future PLC.

Knowing the manufacturer’s specified intervals is essential for maintaining your systems; oil changes on your engine and generator are a great example of time vs hours-based service.

With most engine manufacturers stipulating oil changes annually or at 200-250-hour intervals, what may have been an annual event could quickly become multiple times a year, depending on usage.

Failure to change oil can affect engine performance and damage components. We’ve had to replace one-year-old turbos that have seized due to poor oil damaging seals.

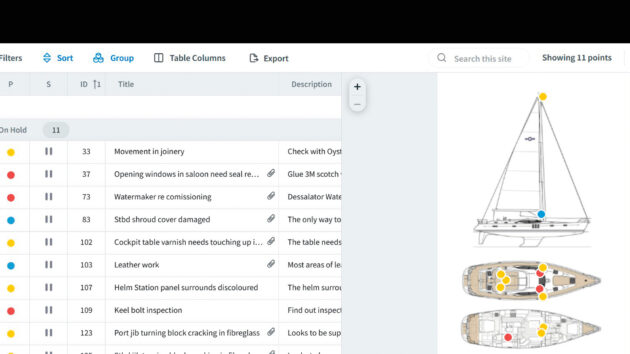

A simple system health matrix (Blue = OK, Amber = needs attention, Red = critical), shown opposite, helps prioritise the attention required on each system. The biggest risk is assuming something is fine just because it worked last year.

Budgeting or an ocean crossing

Engine checks should be carried out daily. Photo: Theo Stocker.

Preparing a boat for ocean sailing will undoubtedly require a larger budget than your previous annual maintenance programmes.

You’ll be bringing forward some maintenance to ensure systems can stand up to the rigours of offshore sailing and to avoid complicated servicing while you’re cruising and exploring.

This certainly applies to saildrive diaphragms, which require specific replacement intervals. Often, replacement is due halfway through a multi-year cruise, and it would be more cost-effective to have it replaced in the preparation period, before your departure.

You can then use a trusted engineer, and no additional haul-out costs would be accrued. If you were replacing the propeller at the same time, you’d further reduce labour costs as the old propeller would need to be removed anyway. Lower leg seals can also be checked.

Once finished, you have peace of mind that only scheduled oil changes will be required during your adventure.

What a realistic budget for an ocean crossing should include

Prioritise spending on systems that matter the most offshore, using your assessment results. Start by categorising jobs into three areas:

- Safety-critical: hull, steering, rigging, sails, safety and communications.

- Essential comfort: power systems, fridge, cockpit covers like biminis.

- Nice-to-have: additional sails, upgraded electronics, water maker

A realistic budget should account for:

- Boatyard services (haul-outs, craneage, storage costs)

- Parts and equipment (refurbish kits, components and consumables – Sikaflex, hose clamps etc)

- Professional services (rigger, sailmaker, electrician, marine engineer)

- Spare parts and tools that you will take with you

- Unexpected contingencies (I’d recommend adding 20% to any initial budget estimate)

Looking at the whole plan can help with your budget. For example, choosing the yard with the cheapest storage and lift-out costs may not be the most cost-effective option if it doesn’t have access to good services on-site.

If engineers subsequently charge travel time to attend your yacht, this could quickly outstrip initial savings.

Work out whether taking out the mast before lifting your yacht is more cost-effective; this will often save costs on additional crane hire and boat movements.

Likewise, if your rudder is too long to remove while it’s set down in the yard cradle, paying for an hour to ‘hold’ it in the slings on lift out will be cheaper than a new yard movement.

Purchasing equipment around boat shows, or outside of peak refit season (January-April) will also give you more value and better lead times and availability on parts.

Planning and scheduling boatyard work before an ocean crossing

Setting a departure date is one recommendation I’d give to people preparing for an offshore adventure. You can then start working back from that.

The ’12-month’ panel is a helpful timeline for a typical transatlantic preparation for the World Cruising Club’s ARC or ARC+ rally, which departs in November, but you can move the timings to suit your own departure time and location.

Lead times for equipment can be fluid, depending on when you order, so factor them into your plans.

New sails, for instance, can have a much shorter lead time if ordered before Christmas, but that can jump quickly if ordering in February-March, with sails not being delivered until early summer.

Book contractors early to keep the project on track. Photo: Graham Snook/Future.

Booking contractors early and paying deposits to secure slots is a great way of keeping a project on track. Also consider the time taken to discuss your requirements, receive estimates or quotes, finalise pricing and parts being ordered.

If a part of the project is happening outside, don’t forget to account for weather delays.

Setbacks to your departure time can have a large impact on the success of your project; it can make it difficult for the crew to plan time off or mean you are sailing outside of ideal passage-making times.

If you’re determined to leave on time but running late with your final preparations, having items shipped to you can be tricky.

Determining delivery times vs passage times can be like trying to hit a moving target.

Alternatively, if items can be delivered directly to your ocean crossing pre-departure point, it won’t give you time to ‘shake down’ the equipment.

Staying on top of your maintenance will avoid costly repairs later. Photo: White Dot Sailing.

The maintenance plan that prevents repairs

After a successful yard period, during which you’ve explored the inner workings of your yacht’s systems, you should feel more knowledgeable and confident in their condition than ever before.

However, without a robust maintenance plan (see panel on the previous page), these systems will start to degrade and eventually fail. An effective plan must account for the miles ahead and the conditions in which the yacht will most likely be sailed.

A great example is your rig. Having spent a good portion of your budget on changing standing rigging and upgrading components, it should be good for 10 years or 30,000 miles – but only if maintained.

With your mast on the ground, your rigger should be able to go through each component with you and explain its use and where it could fail. This can help you create a rig check.

Once the rig is re-stepped and tuned, it’s time for you to go up. Test out your procedures and new bosun’s chair (I also carry a climber’s helmet offshore), take pictures of every component from every angle; they’ll never have been in better condition.

These pictures, along with your checklist, will form the basis of your maintenance plan for this system. Go up before and after every offshore passage and check from deck level with binoculars daily while on passage. Get a professional rigger to check annually and provide a report.

A recent client followed this process religiously during their transatlantic adventures, discovering a cracked wire strand in a lower shroud after their east-west ocean crossing.

Finding it before the point of failure meant we were able to organise a warranty replacement, upgrading from standard to compacted strand.

It was also an opportunity to discuss why it happened, and the prevailing consensus was over-tensioning of their 2:1 spinnaker halyard while sailing a gennaker-type sail.

Spares: what to carry (and what not to) on an ocean crossing

There’s no point in carrying spares unless you have the correct tools to fit them – like a filter wrench. Photo: Stu Davies.

Deciding what parts to take can be a delicate balance; you should carry parts that you can fit yourself or that you envisage would be extremely hard to source. It should also reflect the system’s importance and your refit period work.

You may have bench tested your five-year-old alternator and it produced satisfactory results; however, if it’s your primary method of charging, deciding to carry a spare would be a sound choice.

Many skippers we work with decide to carry a spare propeller, even if it’s a basic fixed blade. In the event they had an issue with their existing one, the only requirement would be a haul-out to replace the damaged or missing one, especially helpful in remote areas.

Carrying every spare part you can think of might seem like a good idea, but it may not be the best use of your budget or space on board. Instead, divide spares into three categories:

- Critical parts you can’t put to sea without: steering cable, spare freshwater pump, fuel filters and engine spares, autopilot parts, short lengths of rigging wire and bulldog clips in case of failure.

- Likely wear/failure: belts, impellers, hoses, shackles, fuses, bulbs.

- Consumables: Sealant, tape, hose clamps, wire, mastic, grease.

U-bolts and shackles can wear on each other, leading to failure. Regular inspection is key. Photo: White Dot Sailing.

Don’t forget specific tools too, like a filter wrench; there’s little point carrying spare fuel or oil filters if you don’t have the means to remove and replace them.

Stowing your tools safely is as important as having them on board; a rusty oil filter that’s been stowed in a damp environment will not be a reliable replacement. Create a stowage plan so you and your crew know where every item is located.

If you carry multiple parts and service kits, make sure you understand how to install them. A perfect time to check will be during the assessment phase, when you’re getting to know your systems in more detail.

It’s a good idea to make sure you have e-copies of all manuals for your boat.

If detailed instructions or manuals are required, it’s a good idea to have them digitised on a memory stick or uploaded to your ship’s laptop or tablet, taking up much less space.

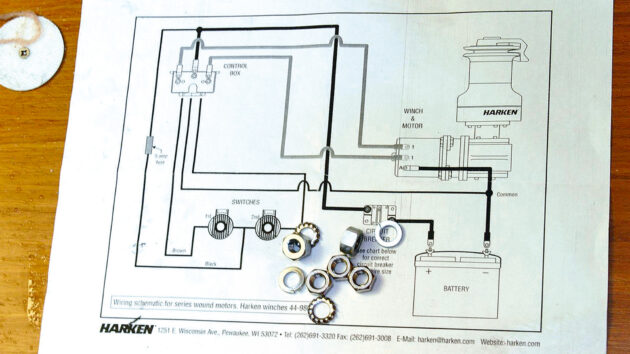

Recently, we supported a client in fault-finding and repairing their watermaker over a Starlink connection while he was offshore. He found the electrical fault by using his multimeter to diagnose a break in a connector, replacing it with WAGO connectors he had on board.

Having a comprehensive fault-finding tool kit is essential to being self-sufficient, especially measuring devices like multimeters (a clamp meter is even better), inspection cameras, callipers, and measuring tape.

You, the skipper: know your systems, then teach your crew

Learn how to isolate and bypass your boat’s systems… and then share that knowledge with your crew. Photo: Katy Stickland.

You don’t need to acquire engineering-level knowledge for all your systems, but you do need to understand how your boat works and be able to do basic checks and fault-finding.

If the problem is simple, you can fix it yourself; if not, you can accurately describe the problem to an engineer or relevant expert; the more accurate the explanation, the better the remedial work will be.

We encourage owners to walk through critical systems with us. That knowledge means they’re likely to turn a potential failure into a manageable fix at sea.

- Know how to isolate and bypass systems.

- Practise basic tasks like fuel filter changes or rig inspections.

- Keep e-copies of wiring diagrams, service history, and manuals.

- Access expert advice or courses to improve your knowledge and understanding.

Once you’ve acquired that knowledge, it’s time to train your crew.

Through my experience coaching as a Yachtmaster Instructor and as a safety inspector with ARC rallies, I often see top-down management in skippers.

Naturally, they are the most knowledgeable when it comes to their yachts and the equipment aboard, but this can lead to situations where all the responsibility, including the to-do list, rests on them.

Being able to delegate tasks to your crew will mean they’re more engaged and motivated, allowing you to enjoy the adventure too.

From overwhelmed to offshore-ready

Delegate tasks on board, otherwise as the skipper, you will soon become overwhelmed. Photo: Richard Langdon/Ocean Images.

Preparing your yacht for offshore sailing can feel overwhelming—but like any large project, if it’s broken down into smaller sections it becomes much more manageable. Start early, prioritise critical systems, and understand where your knowledge is weak so you can engage professional help.

You will need to check, service and maintain each system aboard your yacht. It’s vital to understand your equipment, know the service timelines, and carry the necessary spares. Taking the time to prepare correctly will mean having the time to appreciate the journey and enjoy the destinations.

Remember: your goal isn’t perfection. It’s preparation. Know your boat. Know what matters. Fix what needs fixing.

And then, when you set sail, you’ll do so with confidence.

Your 12-month prep timeline for an ocean crossing

- 12 months out: initial audit. Begin budgeting and list jobs. Book yard time. Lock in contractors. Order parts with a long delivery lead time.

- 9 months out: major works (rigging, engine overhauls, deck gear upgrades). Crew training plan and courses started. Start searching for marinas.

- 6 months out: Safety gear updates. Test sails. Electrical and nav tweaks. Sea trials, emergency drills, and final spares orders.

- 3 months out: Final checks and remedial works, servicing requirements completed.

- 1 month out: Crew refresher on drills and safety procedures. Weather monitoring.

Maintenance plan

Ensure winches run smoothly and inspect and service them every six months if long-term cruising. Photo: Mike Robinson/Alamy.

This is subject to the boat’s mileage, but would be correct for a year with one or two ocean crossings and cruising.

DAILY CHECKS

On passage:

- Sails: check for tears, wear, delamination

- Rig visual check (deck level, but use binoculars for above head height)

- Wire/rod – loose or damaged

- Loose split pins, rings, clevis pins

- Headsail foils not bent and greased furlers operating smoothly

- Fittings secure: radar, lights, aerials

- Check boom and vang gooseneck fittings

- Spinnaker pole and track operable

- Engine checks: water, oil & coolant, belts, bilge clear, batteries, no leaks visible, exhaust. Also, check gearbox/sail drive oil

- Batteries: depending on type, they are not falling below recommended levels (FLA/SLA/Gel/AGM – always above 50% SOC – if calibrated or ~12.1/12.2V, lithium – Battery Management System (BMS) will manage)

- Bilge sump, check dry

- Water level (no heel)

- Fuel level (no heel)

- Gas level

On deck:

- Guardwires secure and split rings located in clevis pins (you can use silicone to captivate)

- Jackstays have no damage

- Organisers/blocks/clutches. Check for damage and no-chafe operation

- Winches operating smoothly

- Covers not damaged: sprayhood, bimini, awnings

- Safety gear is serviceable with no damage (UV will weaken)

- Lifejackets and lifelines – visual check

- Solar, wind vanes, wind steering; aerials are secure

- Crew check: morale and health

WEEKLY CHECKS (in the Marina or on passage)

- Generator checks: water, oil and coolant, belts, bilge clear, batteries, no leaks visible, exhaust (this may be daily depending on use)

- Software updates for electronic systems and chart subscriptions

- Watermaker freshwater flushed if not used or pickled

- Batteries charging

- Mooring: fenders and lines in good condition

- Check freshwater filters and shower drain filters

- Test bilge pumps

MONTHLY CHECKS for an ocean crossing

- Engine/generator: check hours against service intervals

- Skin fittings: operate until they have free movement

- Check spares list and inventory

Steering:

- Quadrant and shaft key secure

- Top and lower bearing for play (can be checked even in a small swell)

- Wire terminations on quadrant and travel on sheaves

- Any universal joints on fixed systems and autopilots are operating smoothly

Six months:

- Sails – drop and inspect

- Furlers – check top furler units freshwater rinse, and re-grease

- Climb the rig and inspect (compare to previous photos of each component). Do this more regularly as required– before and after each ocean crossing. In-mast furling is susceptible to corrosion from salt on the sails

- Winches and windlass – service and inspect

- Check compass deviation

- Check all ship’s papers are up to date

Safety:

- Check fire extinguishers and if powder, rotate/agitate

- EPIRB test (follow manufacturer’s intervals and instructions)

ANNUAL CHECKS for an ocean crossing

- Sails to sailmaker for professional check and repairs

- Covers checked, laundered and reproofed where required

- Professional rigger to check the rig and all components

- Anodes checked and changed

- Rudder and keel visually checked

- Drop rudder and inspect/clean bearings

- Test emergency steering

- Batteries – drop test under no load to check health

- Antifouling renewed (consider three coats if ablative/doing more miles)

- Inspect water and fuel tanks

- Check propeller, shaft/sail drive leg for wear, growth and galvanic corrosion

- Check cutless bearings if present

- Check stern seal

- All safety gear checked, serviced and tested.

- Lifejackets serviced at authorised centre

- Check transducer calibration (depth, speed, wind)

- Drop anchor and chain in the yard, clean and inspect

- Service toilets

Will Spencer is a Yachtmaster Instructor who runs White Dot Sailing, supporting owners preparing for bluewater cruising while enjoying and maintaining their boats. Learn more at www.whitedotsailing.com.

Want to read more articles about preparing for an ocean crossing?

A subscription to Practical Boat Owner magazine costs around 40% less than the cover price.

Print and digital editions are available through Magazines Direct – where you can also find the latest deals.

PBO is packed with information to help you get the most from boat ownership – whether sail or power.

-

-

-

- Take your DIY skills to the next level with trusted advice on boat maintenance and repairs

- Impartial, in-depth gear reviews

- Practical cruising tips for making the most of your time afloat

-

-

Follow us on Facebook, Instagram, TikTok and Twitter