Marine engineer and surveyor Marcus Jones unpicks the confusion surrounding the use of lithium batteries and what you should consider if installing them on board your boat

The lithium-ion battery has enabled so much of the portable tech we take for granted today, from laptops, mobile phones, small VHF handheld radios, portable GPS, to electric cars and bikes.

But these powerful energy storage devices carry new safety risks, which are only now starting to appear, requiring us to draw up clear installation standards, rather than the confusing standards and guidelines from multiple flag states and classification societies we’ve had thus far. So let’s try to clear up some of the confusion about lithium batteries in marine applications and explain the safety challenges that need to be understood to make things safer.

What is a lithium-ion battery?

This is the first thing that needs clearing up. The term lithium-ion is a generic term used to describe all the various chemistry types available, such as lithium nickel manganese cobalt (NMC), lithium ferro phosphate (LFP), and all the others.

Lithium-ion is not a battery chemistry in itself at all. It simply refers to rechargeable batteries that carry a charge via lithium ions in their cells’ electrochemical operation. Sometimes lithium-ion battery is abbreviated to LiB.

How does a lithium-ion battery work?

To understand how a lithium-ion battery works, we need to understand how the cells are constructed. Inside a cell is what’s called the ‘jelly roll’.

It’s made up of a number of layers – think of it as a layer cake. Let’s start with the cathode region, which is made up of an aluminium foil sheet onto which is spread a layer of paste containing the active cell chemistry.

Lithium ferro phosphate is preferred for marine use being slightly more stable than other chemistries, but it’s not immune to a thermal runaway. Credit: Relion

This defines the cell chemistry name. The opposite anode region is made up of a copper foil onto which is spread a layer of carbon particles or soot.

Between these two regions is a polymer separator which is pours to ions. Both regions, and the separator, are flooded with a liquid electrolyte or solvent, which allows for the movement of charged ions between the cathode and anode regions in the cell passing through the separator. The anode region makeup and separator do not change with the cell chemistry type.

Operation of a lithium-ion battery cell

- Charging the cell makes charged ions move from the cathode region to the anode region. The anode region becomes what is known as lithiated when the cell is charged.

- In using or discharging the cell, charged ions move from the anode to the cathode region.

- Electrical energy travels between the regions via the external circuit.

The chemical reaction that enables the movement of charged ions across the cell is exothermic and produces heat energy, which is normal for all the chemistry types we are currently using, as the lithium-ion chemistries are naturally unstable and want to transfer energy from one form to another (electrical energy into heat energy and gas, in this case).

Really, lithium-ion chemistries are not supposed to exist! These naturally unstable chemistries are slightly stabilised with the chemical creation of a passive coating on the carbon particles in the anode region of ‘lithium salts.

Called the solid electrolyte interface or (SEI), this allows the cell to act more as an energy store. However, if this layer is thermally broken down by heating or other damage, the natural chemical reactions take over, and the cell chemistries destroy the cell and battery. It is this unstable nature that can lead to thermal runaway.

Lithium-ion batteries perform poorly in cold temperatures due to decreased ion mobility and higher resistance

What is abuse of lithium-ion?

Lithium-ion battery cells are like people; they don’t like being abused. Abuse can be from overcharging, short circuit, overheating, forced charging at low temperature, over-discharge, impact or physical damage, cell defects or manufacturing faults, and ageing.

In short, anything that damages the solid electrolyte Interface layer can cause the cell chemistry’s exothermic reaction to release energy in an uncontrolled way. One defence against this is the battery management system (BMS) that controls charging and discharging, and monitors cell temperature and voltage, along with thermal cooling, for example.

In large-scale systems, a high degree of integration between safety monitoring systems is being tried to reduce the occurrence of thermal runaway; many smaller systems don’t offer this level of monitoring integration yet.

A battery management system (BMS) controls charging and discharging, and monitors cell temperature and voltage. Credit: Fathom

Do I need a battery management system… And what is it?

The battery management system is a vital defence against abuse of a lithium battery, regardless of chemistry. It will monitor various conditions at either the module or battery level or at cell level.

However, it will not halt thermal runaway once it’s started. Ageing battery cells degrade at different rates and thermal runaway thresholds can fall.

A new battery might have a temperature threshold of 180°C, and a BMS monitor will shut off a cell at 160°C, but an aged cell might reach thermal runaway at 100°C or lower. This means that other mitigation measures should be built into installation designs from the start.

Electric vehicle (EV) batteries should not be repurposed for use on a boat as they’ve not been designed for marine installation. Credit: Bloomberg/Getty

What is thermal runaway and thermal propagation?

‘Thermal runaway is not a fire, it’s heat’. This is a very simple statement, but it’s often forgotten.

By reducing thermal runaway to just fire, we ignore vital details that produce serious new hazards. The heat of thermal runaway comes from the unstable reactivity of the cell chemistries that release energy in an uncontrolled way as heat and gas.

The chemical reaction becomes self-sustaining with heat increasing the reaction, which produces more heat, and more chemical reaction, and so on, until all the energy in the cell has been released.

All the current chemistries can experience thermal runaway, but will express that thermal runaway in different ways, creating different primary hazards and risks, and have different thresholds that depend not only on chemistries, but also on cell form, state of charge, age of cell, and other external factors.

The additional part of thermal runaway is thermal propagation. This is how thermal runaways spread in a battery made up of multiple cells.

The cells in thermal runaway heat the unaffected cells, which then join in with thermal runaway. This propagation is not just directly cell to cell; it can spread randomly within a battery, even from battery to battery within a battery bank.

Some success has been made with the control of thermal propagation within batteries or modules.

What risks can thermal runaway produce?

Thermal runaway has a number of possible outcomes.

- The battery or module simply explodes.

- The battery vents huge volumes of flammable and toxic gas which, if ignited, can produce rocket-like focused flames which can start a fire by setting fire to other things.

- If gas ignition is delayed, or a flame jet is extinguished, thermal runaway continues and creates an explosive atmosphere which can be ignited by another source or by the heat of cells in thermal runaway. This causes a vapour cloud explosion (VCE).

- If a vapour cloud explosion occurs within a confined space, it has a lot of destructive force. A confined VCE occurred on a narrowboat at Gayton Marina in the UK on the 5 August 2025, destroying the boat, which, according to the Northamptonshire Fire and Rescue Service, was fitted with lithium iron phosphate (LiFePO4) batteries.

- Regardless of chemistry, thermal runaway can’t yet be extinguished, as cells are watertight and fitted within a waterproof case. Control of the spread of any ignited external fire, however, will buy time.

A basic automatic fire protection system on board could limit damage and buy time

So what hazards are missed if we reduce thermal runaway to a fire?

Active fire is not required for thermal runaway to be present. In fact, it’s not the battery, or cell, that is burning; it’s the gases vented by the chemistries that bring the hazards.

Lithium-ion in thermal runaway can vent a huge volume of flammable and toxic vapour. Typically, estimates range from 300lt to 5,000lt per kilowatt-hour of battery capacity.

Each type of chemistry generally expresses thermal runaway differently. Only a small proportion of the vapour is visible. This can be mistaken for steam or smoke, but it’s not!

This visible vapour is droplets of electrolyte from the cells, and is flammable. The vapour cloud also has two densities, one lighter and the other heavier than air, which can make ventilation to prevent build-up a challenge.

How is thermal runaway different between chemistries?

The most common chemistries in use are lithium nickel manganese cobalt (NMC) and lithium ferro phosphate (LFP), with LFP being preferred for marine lithium-ion batteries.

NMC LiNiMnCo2 (lithium nickel manganese cobalt oxide) is a very energetic chemistry and, in thermal runaway, produces very rapid chemical reactions and heating, often igniting vented vapour within seconds, so rocket-like flames and fire are the primary hazard, coupled with a very high volume of vented gases, which can produce 2m-long jets of flame at 1,000°C. The vapour has a lower explosive limit (LEL) of 11% when mixed in air.

LEL is the lowest concentration of a gas or vapour that will burn in air. Lithium ferro phosphate (LFP-LiFePo4) is slightly more stable and harder to push into thermal runaway and thus could be considered safer in some ways.

But, it is not immune to thermal runaway, and will vent off vapour without early ignition; this allows it to create explosive atmospheres within confined spaces. It produces a lower overall volume of gas compared to NMC, but has a higher toxicity than NMC, with higher volumes of hydrogen and ether in the vapour with a LEL of 5%, which is much lower than for NMC vapour.

This higher proportion of hydrogen and ether and lower LEL means that the explosive power of the vapour is much higher than that of NMC, despite the lower overall volume. The lithium ferro phosphate (LFP) cells are less reactive than NMC, so vapour is often ignited by another source before the cells or the case becomes hot enough.

Make sure the monitoring system has its own power supply and shows temperature and battery alarm state. Credit: Mike Attree

What is a ‘drop-in’ lithium-ion battery?

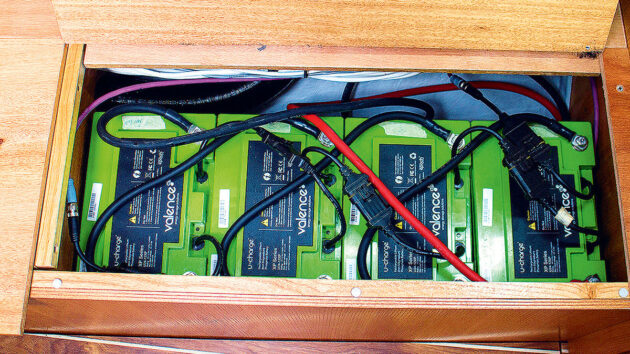

The simplest form of battery module available is what is termed a ‘drop-in’. These are similar in size, shape and terminal layout to common lead-acid batteries, the idea being that they can be dropped into the same holders or boxes as any existing lead-acid batteries and are marketed as a plug-and-play solution.

They have a built-in battery management system, often monitored via a Bluetooth wireless connection; some have a heating system to allow the batteries can be used in low temperatures.

In general, they offer very little in terms of safety integration options; however, some manufacturers supply reasonable monitoring systems. In reality, the safe installation of lithium-ion batteries requires a complete and integrated solution that will make the difference between losing the battery or losing the whole boat.

How can I install a lithium-ion battery as safely as possible?

Ensure you buy lithium batteries from reputable suppliers. Credit: Mastervolt

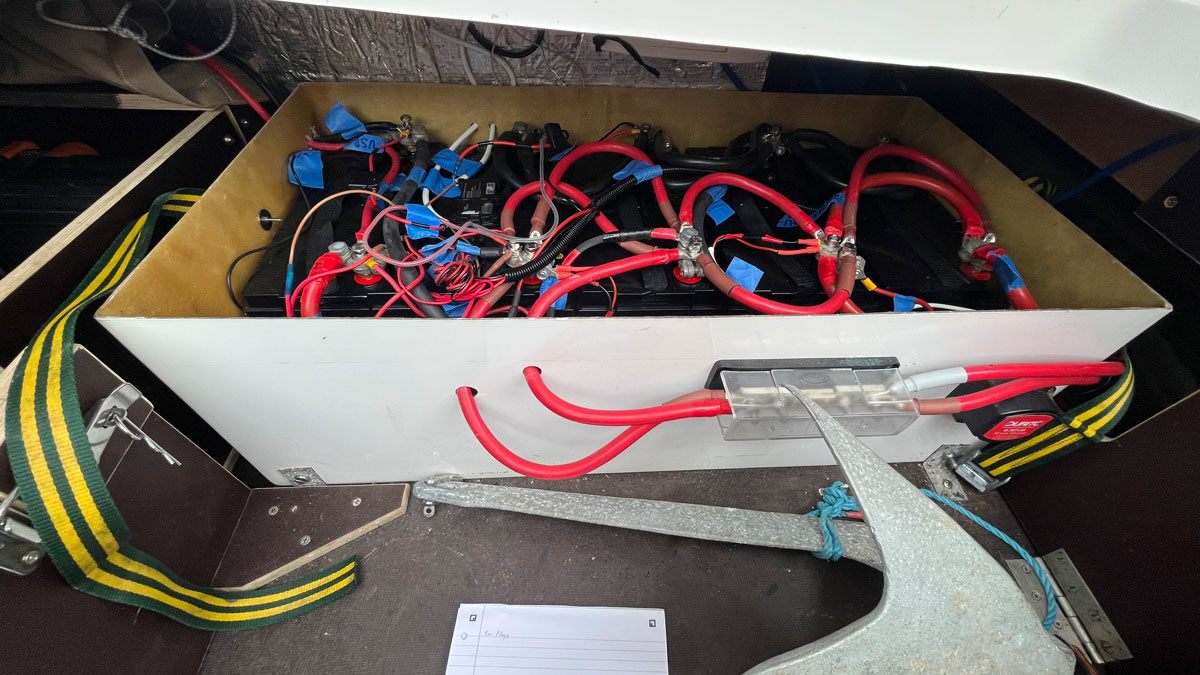

Any installation has to be especially designed for lithium-ion batteries; the idea, for example, that an existing lead-acid battery installation can be safely swapped out without physical modification of stowage arrangement, position, and electrical systems is a real safety concern.

There are also issues with the re-purposing of electric vehicle (EV) batteries and using domestic battery energy storage systems. Neither of these is designed for marine installation. A lithium battery installation requires a level of integration and quality much higher than an existing lead-acid battery would.

So:

- Choose modules or high-quality batteries that are designed for marine use.

- Have the electrical system checked for condition; a redesign will be required before installing lithium-ion batteries in nine out of 10 cases.

- Have the inspection and installation completed by someone competent to do so. Seek consultation and planning advice. Ask questions about the safety features of any installation design. Finding knowledgeable people can be hard at the moment, as there is not yet any formal accreditation system. Use slightly more stable chemistries such as lithium ferro phosphate, but don’t regard them as immune to thermal runaway and make provision for it. Don’t install batteries of any type within a cabin space under a berth or in a locker that vents into the cabin or wheelhouse.

- Use a battery management system that is external to the batteries and gives a warning of battery failures before things become really bad. The BMS should include temperature monitoring of cells, and disconnect cells early if they show signs of overheating.

- Any monitoring system should be continuous with its own power supply, not fed by the batteries it is monitoring. It should also show temperature and battery state even in alarm conditions.

- Consider the installation of heat and gas monitoring, linked to the BMS or to an alarm and monitoring panel on the bridge. Do not just rely on a mobile device, like a smartphone.

- The installation should include ventilation arrangements, possibly forced with fans that are intrinsically safe. This could offer some cooling for batteries and vent the heavier vapours safely away from the cabin or other spaces within the vessel.

- Install a basic automatic fire protection system to put out any external fire. This will not prevent or halt thermal runaway, but it will limit the amount of damage and buy time by controlling thermal propagation within the battery space.

- Ensure that the crew understand what to do if a thermal runaway is suspected or occurs… and also what not to do (see panel, far left).

How To Respond To A Thermal Runaway

When making a Pan Pan or Mayday call give details of the batteries and their location

- Fire and explosion are highly dangerous at sea. Fire can spread rapidly, so early detection and a good, well-planned response can save lives.

- If vapour is seen that looks like steam or smoke, raise the alarm with crew.

- Don’t ignore any battery condition or battery management system alarms.

- Isolate the affected batteries from the electrical system. Ensure the crew knows how to do this.

- Don’t enter the battery space or stowage area, or spaces that might be filled with vapour. Exposure to the highly toxic vapour requires complex medical treatment.

- Make a Pan Pan or Mayday call, include the fact that lithium batteries are aboard, and any details of the chemistry type. If in harbour, give information on where the batteries are and how to isolate them. A good vessel plan can help.

- Ventilation of a battery space to the outside atmosphere early on can reduce the risk of a vapour cloud explosion. But stay clear of any open hatches or vents and vapour cloud.

- Muster to abandon the vessel to a liferaft or attending RNLI lifeboat.

- Fighting a fire will buy time. Use any fixed system as required to suppress the spread of a fire and keep evacuation routes clear.

- Portable chemical or water fire extinguishers can also be useful, but we don’t yet have a means of extinguishing thermal runaway. Gas fire extinguishing agents don’t work as they offer no cooling effect on cells.

Marcus Jones runs LSE Marine (lsemarine.com) based in Devon, and is a marine surveyor and accident investigator. He sits on the Institute of Marine Engineering Science and Technology (www.imarest.org) working group, drafting and improving international standards for lithium battery installations, and the Maritime Battery Forum group examining emergency response to thermal runaways.

Lithium iron phosphate batteries: myths BUSTED!

Duncan Kent looks into the latest developments, regulations and myths that have arisen since lithium-ion batteries were introduced

Industry insight: lithium marine batteries and other power options

A lot of people are wondering whether to switch to lithium marine batteries, but don’t actually know what they should…

Insurance cover concerns over lithium batteries

Boat owners are being urged to contact their insurers before switching to lithium batteries to check their insurance will still…

Lithium batteries vs lead-acid batteries: What are the key differences for boat owners?

But even the best lithium batteries do have downsides, writes Emrhys Barrell . The first is cost, at up to…

Want to read more articles like Latest lithium-ion battery advice that every boat owner needs to know?

A subscription to Practical Boat Owner magazine costs around 40% less than the cover price.

Print and digital editions are available through Magazines Direct – where you can also find the latest deals.

PBO is packed with information to help you get the most from boat ownership – whether sail or power.

-

-

-

- Take your DIY skills to the next level with trusted advice on boat maintenance and repairs

- Impartial, in-depth gear reviews

- Practical cruising tips for making the most of your time afloat

-

-

Follow us on Facebook, Instagram, TikTok and Twitter