Richard Barnard is reminded not to get engine dependent in fickle winds, sailing his Coaster Passagemaker 33 off the Suffolk coast…

Sailing, with the wind, sea and tides, is a sport ever ready to reward complacency with challenge. From an estuary dinghy sailor to an ocean voyager, there are endless opportunities to learn something new – from a better way to lead the jib sheet to how to heave-to more safely in a gale.

The years go by, your experience widens and your skills develop – but sailing also has a way of reminding you of the basics and this happened to me off the Suffolk coast.

It was September and time to return my motor-sailer to her River Colne berth in Essex after a summer on the River Ore in Suffolk. I’ve done this 35-mile passage many times solo in a variety of yachts.

The main challenge is to cross the bar at Orford Haven with enough south-going flood to get into the Colne before the ebb sets in. With my home berth being tidal, whatever I do involves a night at anchor, either in the River Orwell or in the Colne, awaiting the next day’s tide upriver.

This season the Ore bar was crossable three to four hours before high water, and with a forecasted east to north-east 3-5, veering east or south-east later, I would have four to five hours to sail, or motorsail, with a fair wind the 27 miles from the Ore bar to the Colne. With a good spring flood tide under me as well, this would be easy.

Article continues below…

Lessons learned from sailing home in a Force 5 after engine failure

Philip, my husband, needed the car so I decided to take my Offshore 8m Karima S from Aith to Brae,…

Mud team to the rescue! Lessons learned from running aground on a sandbank

Paul Simon used to sing to me that ‘the nearer your destination, the more you’re slip-slidin’ away’. I never knew…

Exhilarating start

I spent the first night downriver from my mooring, anchored beside Havergate Island, three miles from the entrance. I weighed anchor at 1100 to motorsail over the strong flood tide, aiming to cross the bar at 1215. The breeze was south-east and on the beam, Force 3-4.

With the sails pulling nicely we cleared the river mouth and approached the bar along the beach at Shingle Street. As we motored close to the beach, I was acutely aware that this was a very close lee shore. We were away from the worst of the foul tide, in a good breeze, but the thought of engine failure and the need to do short tacks in shallow water over a notorious bar added a sense of excitement.

All went well. We turned offshore and over the bar in 9ft of water, plunging the bow a few times into the confused seas around the Haven buoy, sails lifting as we motored through. In 10 minutes we were clear and bearing away to head south-west down the coast, logging seven knots over the ground with the fair tide. Just as I was thinking about cutting the engine, the decision was made for me.

Yachts at anchor at Pin Mill on the River Orwell. Photo: Alamy

It hesitated, idled irregularly and then ground to a halt. I was very grateful that this hadn’t happened 10 minutes earlier! My Coaster Passagemaker sails well and I had a fair wind and well over four hours of fair tide to get into the Colne so I wasn’t unduly concerned.

I connected the Tillerpilot and checked her speed – six knots. I could get to the Colne anchorage by high water and worry about getting into my berth tomorrow.

As we slipped along in the sunshine towards the River Deben entrance, the breeze faded and the speed dropped accordingly. The noon inshore waters forecast now mentioned the possibility of a shift to the south-west ‘later’. This shouldn’t affect me, but I did not want to be engineless on the coast towards the end of the day with a foul tide and the prospect of a heading breeze.

Osprey, Richard’s Coaster Passagemaker 33

So, while the Tillerpilot did its sterling work in the easy conditions, I hauled the ghoster out of its locker and onto the foredeck. Furling the jib, I spent the next 45 minutes trying to untangle the snuffer lines before giving up and hoisting it with the snuffer secured at the top. The speed picked up a treat and, as we approached the Harwich Harbour entrance, things began to look rosy again.

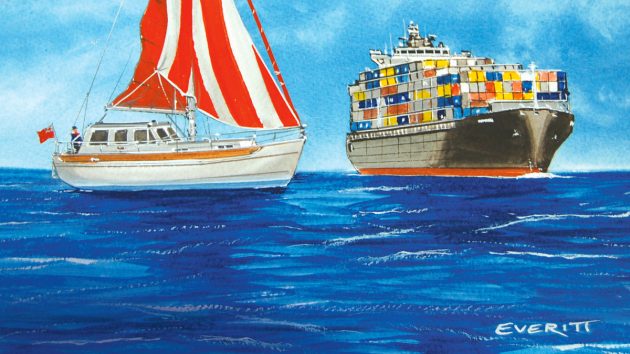

Then I noticed the container ship on my quarter, coming along the channel ahead of me. I knew I’d have to let her through, reinforced by the blasts from her horn. I gybed and lay her hove-to on the other tack while the ship plodded ponderously along.

She eventually passed ahead and I was able to cross, now further downwind and much nearer to Harwich, requiring me to take the helm and bring the wind forward of the beam to steer a course to squeeze her past the Naze headland ahead.

Osprey’s tidal River Colne berth requires a night at anchor, to await the next day’s tide upriver

With sheets in and the ghoster still setting, she slipped along nicely, albeit now at a reduced speed, with the fair tide now slowing down as well.

By 1515 we had cleared the Naze and I eased the sheets to reach along the coast. I took stock. There remained just over an hour of fair tide left, fading fast. Bearing away had also reduced the apparent wind and she was only making four knots in a breeze that was now also fading.

It was 12 miles to the Colne and it would be getting dark in a few hours. Did I really want to be adrift off the Essex coast, in a foul tide, drifting backwards as the sun set?

Safe haven

I pulled down the ghoster, unfurled the jib and gybed round to broad-reach towards Harwich. It was eight miles to my intended anchorage beyond Felixstowe Docks, and the fading breeze and turning tide meant I had to creep in over the ebb tide.

But at least I was safe and, if judged properly, I would have fair tides all the next day. I checked the fuel filter by loosening the drain valve, nothing ran out, so it was blocked.

I had a spare, but the unit was not easy to access and I was unsure about the bleeding process afterwards. With a fair weather forecast and help from the tides, I knew I could get home without using the engine. But getting into the mud berth…

Low tide on the River Colne at Wivenhoe near Colchester, Essex. Photo: Gary Eason/Alamy

I weighed at 0600, allowing over four hours to cover the eight miles to the Naze to catch that fair flood tide. With a fickle Force 1-2 headwind, we slowly tacked out of the harbour, allowing the ebb tide to do most of the work. In the early quietness this was surprisingly pleasant.

By late morning the breeze was filling in nicely and holding in the south-east, letting me reach down the coast and up the Colne with plenty of time in hand. Rather too much time. As we crossed the Colne bar I realised that I had seven miles to go to my quayside mud berth, and two and a half hours to cover it, with a Force 4 on the quarter and a spring flood tide under me!

So I sailed with a scrap of jib to give steerage way, then under bare poles, even broadside to the tide at times, using a bit of jib to throw the head round the bends upriver. The Saturday sailors must have wondered what I was doing.

Mud stop

We arrived at the berth with half an hour of tidal current still to run, flowing across the entrance to my mud berth. I would only get one bash at this, and I hoped it wouldn’t involve my neighbours’ boats.

Once through the Colne Barrier at Wivenhoe, and with a gentle breeze blowing behind, I unfurled the jib, gained steerage way, swung her across the river and we reached nicely into the berth, the lovely mud braking her to a neat halt.

The trip had reminded me of some basic sailing skills, insidiously weakened by years of reliance on the use of an engine to take away the concerns about making a passage in fickle winds and fair and foul tides.

Lessons learned

1. Whatever you sail, and for any passage more than six hours, the tide has to be your friend, and any passage plan has to include options for gear or engine failure. This is in any sailing manual, but I’m not sure we all include this all the time. I didn’t, which is why I kept going against the odds when the engine stopped. I should have just sailed straight into the Orwell for the night and avoided those concerns about achieving the original passage.

2. Make sure all your gear is working properly. I hadn’t, as I had a ghoster with a snuffer that was tangled. Sorting this out wasted 45 minutes – time that would have been spent sailing a knot and a half faster and across the deep water channel before the container ship arrived, avoiding a further half an hour of wasted time hove-to and lost ground to leeward. I would have arrived at the Naze well over an hour earlier, which would have given me enough fair tide to get me into the Colne before high water.

3. In gentle breezes, many of us just reach for the engine switch. It pays to sail your vessel once or twice to see just how much ground she can actually cover under sail and to gauge your passages on that experience. I hadn’t done that with this yacht and had over- and under-estimated what she could do in the breezes I had available.

4. The following week I had a new Separ fuel filter and water separator fitted, bigger and much more accessible. I discovered that this is also self-bleeding after the filter element is replaced, making that process much easier. So there are indeed always lessons to be learnt, but also some useful reminders as well.

Expert advice

Expert advice

Royal Yachting Association (RYA) Cruising Manager Stuart Carruthers responds: I think Richard Barnard has summed up the lessons learned pretty well and needs no lessons from the RYA; it is a fact that engines do fail, even the best maintained ones!

He is to be commended for an excellent article which should give all readers food for thought when planning a trip, for knowing how to deal calmly with the challenges as they emerged and for being able to sail his boat to its berth.

Why not subscribe today?

This feature appeared in the July 2023 edition of Practical Boat Owner. For more articles like this, including DIY, money-saving advice, great boat projects, expert tips and ways to improve your boat’s performance, take out a magazine subscription to Britain’s best-selling boating magazine.

Subscribe, or make a gift for someone else, and you’ll always save at least 30% compared to newsstand prices.

See the latest PBO subscription deals on magazinesdirect.com