Carl Bennett runs the low tide gauntlet at Martlesham Creek and experiences the additional problem of a chewed up tender when his Folkboat goes aground…

Paul Simon used to sing to me that ‘the nearer your destination, the more you’re slip-slidin’ away’. I never knew he’d sailed the Suffolk coast.

It was mid-summer and I had a Folkboat moored at the end of Martlesham Creek, which as anybody familiar with either of those things will know, limited my sailing opportunities. A Folkboat needs 1.19m of water before it will float.

At the furthest end of the creek where I was moored that means you have about 90 minutes maximum either side of high water to go and do whatever it is you want to do before you have to wait for another tide.

But it was sunny and I was keen to get afloat. I’d spent several years refitting Fern and bringing her back to her former beauty, albeit through a catalogue of mishaps that made me regret ever seeing the boat in the first place.

The electric fire was one such incident I would prefer to forget. The starter motor jamming is another. Claims by some that my particular model is prone to jamming didn’t help: if that is the case, one wonders why the manufacturer doesn’t sell a kit for stopping it – it would save me from using a hammer!

Article continues below…

Heaven help us! Lessons learned from repeat boat breakdowns

Don and Renae Shore had flown down from Minnesota to join us in Florida for a week’s cruise, to experience…

Lessons learned after yacht sinks during grounding recovery

“We deserved to get away with a few scratches and a bit of embarrassment, not to get the boat sunk”…

Swan lake

The thing that really hindered Fern’s renovation occurred the previous summer, after several years moored to a jetty, when we decided she was ready to go out into the creek to actually sail her while the restoration work continued.

There were other boats moored-up tight all around us, but the motor fired up first time without needing a hammer action on the starter clutch casing at all.

We slipped the lines fore then aft in best Bristol fashion and clunked the gearbox into reverse, all the while thinking about prop-walk and trying desperately to ignore the fact it was about 15 years since the last time I’d reversed around crowded jetties and moorings in a sailing boat.

Setting off down the creek at high tide

At first it all seemed to go smoothly. At HW or thereabouts we got clear of the other boats and, using the good two or three feet of water underneath us, pushed the tiller away to start the epic hundred-metre voyage to the mooring.

Nothing doing. ‘Ha, prop-walk,’ I thought. That or prop-wash. Or maybe cavitation. Whatever, I pushed the tiller the other way. Still nothing doing.

It didn’t make any difference what I did. The tiller moved, the headstock on the rudder turned, but Fern didn’t. She just charged backwards across the creek heading for the mudbank and the swans on the other side.

I was attacked by a swan when I was a boy and remembered it like a slow-motion feathered hissing car crash. I didn’t fancy 30 of them being annoyed by my boat busting up their party.

I put the engine into neutral then into forward to slow us down and stop, which we did after running straight over some moorings, somehow not getting fouled on them.

Then I remembered the tide was running now, and not only were we going to be moving through the water, but soon there wasn’t going to be any water.

Waders on

What there would be was mud. Lots of it. I’d been in it before and I didn’t ever want to try that again. I’d wanted to have a look at what was happening to Fern’s rudder, after I’d let it lie over to one side when the tide went out.

Another victim at the yard told me from his own boat my rudder didn’t look right, so I had to see for myself. I tied one end of a line around my waist, the other around a mooring cleat, put the boarding ladder over the side, put some old fishing waders on and dropped a big sheet of plywood down to approximately where I needed to stand.

I thought about taking a handheld VHF with me, or a phone or a whistle and decided that any of that would be ludicrously melodramatic. I found out that it wouldn’t have been.

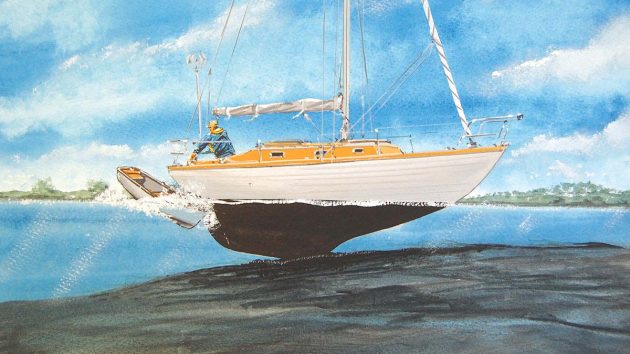

Fern, Carl Bennett’s restored Folkboat moored at the end of Martlesham Creek

The sheet of ply disappeared under the mud as soon as I stood on it. My feet did too, as well as my ankles and shins. Then my knees. If it’s ever happened to you, you’ll know the feeling. If it hasn’t then trust me when I say it isn’t one you want.

It only hurts when you move. And whether you do or don’t you sink a bit more. Pull one leg out, getting several muscle strains while you do it, and the leg you left in the mud sinks deeper. You have to put the sort-of free leg down to pull up the stuck leg, which is now down to mid-thigh level. That hurts, getting it out.

You discover your hands are useless at shifting mud. You remember more stories of wild-fowlers, young men on Camber Sands and Chinese cockle-pickers being stuck and drowned than you ever thought you knew. And I remembered the yard owner telling me about the skeleton of a horse he’d found when he was dredging new moorings.

Boats that have seen better days in Woodbridge, Suffolk. Photo: David Penrose/Alamy

I had to shed the waders and if I hadn’t had the rope as well as the boarding ladder to get me out it might have been a different story altogether. Between that episode and the voyage with the tiller that didn’t do anything, Fern had managed to crack most of her rudder clean off.

This summer though, I’d found a used Folkboat tiller, driven to Lymington and back in a day to collect it, got a stainless mounting bracket made up by the local engineering works which made Maggie Hambling’s Aldeburgh shell sculpture and Fern was actually sailable.

New mishap

I hoisted the mainsail and the jib, sheeted them in tight and motored out through the winding buoys to the end of Martlesham Creek, along Troublesome Reach – which for a change wasn’t – then turned down river through the moorings.

I wasn’t going as far as the sea, but I wanted to see how far I could sail before I had to turn back. Predictably, the wind dropped as soon as I turned the engine off. I’m old-fashioned – if I’m going sailing then what I want to do is sail.

Martlesham Creek Mud flats on the River Deben. Photo: Alamy

For about a half-hour Fern and I got to know each other going gently down the river on what wind there was, then carried by the ebb.

We passed the stone jetty of Coprolite Quay on the north bank and instead of playing around sailing points of the compass in the big pool as usual, we headed slowly down through the moorings upstream from Waldringfield Yacht Club, keeping well away from the ‘island’ in what looks like open water, which is anything but.

As we passed the pub on the west bank I looked at my watch and decided it was time to turn back. Uncleat jib and main, push the tiller over and feel the resistance that shows the rudder is still attached.

Another hazard to avoid

Fern was still ambling steadily downstream. Sheet in and try again. Same result. With just not enough wind Fern wouldn’t tack through the tide. It was time to turn the engine on.

I suppose in other boats there’s a quicker way of doing it, but in Fern the procedure is to open the hatch over the engine, latch it so it doesn’t fall on your head, kneel down, prime the diesel pump then push the start button. You can’t really do it in less than two minutes.

You can’t do it while being swept downstream either, as I learned when we contacted 50ft of Essex’s finest glassfibre and a bemused family of four had their lunch interrupted, first by Fern and then by my decrepit tender on a short line astern banging into their nice, shiny boat.

The Waldringfield Harbour Master came out, tried to pull Fern back upriver and after a while decided that, like Quint, he was going to need a bigger boat. Free of any charge, and without even calling me an idiot out loud, his second attempt to tow Fern off the jammed mooring line actually worked.

Once he and I were satisfied Fern’s engine and rudder were doing all they could he sent me downstream to turn, well away from anything else moored, and waved me farewell. I think that was the gesture. He was gone by the time I came back through the moorings upstream, under power. Fern’s diesel always behaved very well. If it started at all.

Mud countdown

Time was now running out to get back on my mooring at the far end of Martlesham Creek. Cutting the corner at Buoy No8 opposite Kyson’s Point was a calculated gamble I lost. Fern slowed, the water behind us turned a cloudier brown than its normal browny-green and we smoothly but quickly slid to a halt. I put the engine into reverse and revved it.

Judging by what happened next I think we actually came unstuck. We certainly went backwards while the tender obeyed the laws of momentum and didn’t. The towing line wrapped itself around Fern’s propshaft and pulled the tender’s bow under. There was an appalling clunking noise as the prop chewed the tender up.

Coupled with the chunks of fibreglass raining out of the sky I had the insane idea for a nanosecond that we were being machine-gunned until Fern’s engine stopped, the tender sank and Fern started to settle. Common sense should have told me that as we were already aground there wasn’t any danger of the tender pulling four tons of Folkboat under the water, but common sense was in short supply that day.

I whipped out the trusty emergency knife and cut the tow rope. It was tidy and satisfying but it didn’t make much difference. What was less satisfying was Fern settling on top of what was left of the now upside-down tender and cracking it untidily in half.

I was stuck until 90 minutes before the next high water, which was going to be about 0200 tomorrow morning. I was in no danger of sinking. It wasn’t cold to start with, despite being an English summer, but it soon got chillier. There was an old bottle of water on board, emergency energy bars and even an onboard loo.

What there wasn’t – and should have been – was a space blanket. Nor my mobile phone, which I’d left on the passenger seat in the car, in the carpark the other end of the creek. I had my old handheld VHF though, so I put out a call on Ch16, but to no avail. Kyson’s Point being picturesquely set in a natural bowl with tree-covered hills all around, nobody with a VHF could hear me.

Long wait

A walker happened along at that point. I’d written down my wife’s phone number on the notebook I’d remembered to bring with me instead of anything more immediately useful so I shouted out her number to him and asked him to call her if he had a phone. He did. Just tell her I’m going to be late. Like about seven hours late. Could you do that? You will? Thanks.

I didn’t have much to do after that. I put my two anchors out, fore and aft, then when I noticed Fern starting to list to starboard I whiled away another half hour recovering one of them and throwing it as far out to port as I could as the tide went out. I went below and did an inventory of what was on board that could be useful and came up with an impressively short list. A kettle and teabags but no stove was pretty near the top.

I wasn’t stupid enough to even think about getting down into the river bed, or swimming for it. All I had to do was sit and wait for the water to come back. I even had a damp book, though I wouldn’t have anything to read it by after dark. The first few pages showed there was a reason it was left on the boat instead of being read at home long ago.

I went back on deck to get more light to read as there was nothing else to do. Over on Kyson’s Point, about 200 yards away, the owner of the big house with Dutch gables and its own little boatshed was talking to six or seven people in grey coveralls with hi-viz flashes.

‘Please tell my wife I’m going to be late. Like about seven hours late’

A lot of glances were coming my way and I had a feeling about what was coming next. The guy who owns the boatshed got a dinghy out and launched it into the water. He was forced to row three Mud Rescue team members out to my boat.

Everyone was wearing anti-Covid masks, so it wasn’t that easy to hear what the hi-viz crew were saying. What the boat owner was thinking was pretty clear from his expression though, starting with ‘why don’t the Mud Rescue team have their own boat?’ And ‘if they’re commandeering mine, why don’t they row it themselves?’

They were very polite. I told them all I was in no danger, I certainly wasn’t sinking any time soon and my survival plan was to simply sit there until the water came back. I wasn’t best pleased to be told that, ah yes, that was all very well, but they had to enquire about my mental wellbeing.

I accepted a row back to the north side of the creek, under the lee of the Dutch gabled Big House and its slightly disgruntled owner, rendered no less gruntled when the Mud Team decided there wasn’t room for me in their commandeered rowing boat, so they ordered it back to shore to discharge one of their crew then ordered it rowed back to collect me. At that point the owner ordered them all out and collected me alone.

After a brief debrief onshore about who I was, did I know where I was, how had I got there and why, I thanked the rowing boat owner and walked back with the Mud Crew leader the length of Martlesham Creek to get my car and drive home for dinner. On the way he told me why they’d turned out at all. The walker on the river bank had called my wife, then she phoned the boatyard where Fern lived on her moorings and asked them if they could take their workboat downriver and tow me back.

They said they couldn’t, because if I didn’t have enough water then they didn’t either. There was nothing they could do but if she was concerned then, flippantly, they suggested she could call the Coastguard. My wife doesn’t do flippancy, so that’s what she did.

Lessons learned

- There were several things I could have done. One was to bring my phone with me. Finding out my Folkboat wouldn’t tack through an ebb tide in the middle of crowded moorings would, on reflection, have been better.

- I should have made sure there was a space blanket on board or brought a sweater with me; preferably both.

- Cutting across a sandbank on an ebb tide was dim at best.

- It wasn’t dangerous so long as I stayed on the boat but it was certainly inconvenient. Although I had little to do with events as they panned out, it was down to me that the Mud Rescue Team were out looking for me while they could have been looking after someone in real trouble.

- As for the sailor home from the sea, he learned that devoted, concerned and caring wives are to be cherished and treasured. And that, I was told, is official.

Why not subscribe today?

This feature appeared in the April 2023 edition of Practical Boat Owner. For more articles like this, including DIY, money-saving advice, great boat projects, expert tips and ways to improve your boat’s performance, take out a magazine subscription to Britain’s best-selling boating magazine.

Subscribe, or make a gift for someone else, and you’ll always save at least 30% compared to newsstand prices.

See the latest PBO subscription deals on magazinesdirect.com