Modern, light displacement boats may dominate boat show floors, but for true bluewater sailing, the comfort and stability of a heavier hull can be your greatest asset. Ali Wood explains how boat displacement measurements can impact handling, as well as your cruising comfort.

How well do you feel like you understand boat displacement? For most sailors, it’s an overlooked topic.

When I returned to marine journalism after a spell working on other magazines, I was surprised to hear it suggested that heavy displacement yachts were a thing of the past.

‘But what if you hit heavy weather?’ I asked. I was told, ‘You don’t, if you’ve got the routing software apps.’

And so began my sobering education on all things that had, or were soon to become, redundant, from SSB radio to paper charts and radar.

I’m glad to say that a decade later, all of these things are still very much in use, and I did feel at least a little vindicated when ARC (atlantic rally for cruisers) skipper David Diaz told me unequivocally that no boat can outrun a squall, not even his lightweight performance catamaran.

However, talking to David after his 3,000-mile voyage reinforced my understanding that seaworthiness and safety rely not just on boat design and/or the right tech but also the skill and preparedness of the crew.

Knowing how your boat reacts in different sea and wind conditions is part of this, and your boat’s displacement – when combined with other factors – can tell you a lot before you’ve even left the dock.

Modern production boats are indeed built with much lighter materials, and generally have a lower displacement for their length than in the past, but there are still medium and heavy displacement boats on the market, both new and second-hand, which might be perfect for your type of sailing.

[LEFT] UPWIND DISPLACEMENT – Upwind, newer, more efficient hull shapes aid their ability to point when sailing upwind. [CENTRE] LIGHT AIRS DISPLACEMENT – In very light winds, some modern boats with large wetted surface areas and modest sail plans can be slower downwind than older, smaller boats. Photo: Graham Snook.

What’s meant by boat displacement?

A displacement hull (as opposed to a planing hull, which skims the surface) pushes water aside as it moves: the heavier the displacement, the more water is pushed aside. Displacement boats are generally slower, sturdier and more fuel-efficient (up to a point).

So: do you choose a heavy boat that holds its line through big seas and strong winds, or do you opt for a light, quick one that skips and bounces across the waves?

While many of us have the option to simply not set sail in challenging weather, if you’re already making passage you don’t have that luxury.

A bluewater sailboat therefore, would be looking to meet category a (ocean) of the Recreational Craft Directive (RCD).

The rcd describes a boat according to the maximum wave and wind conditions it can handle, from a (extended voyages where conditions may exceed force 8) to d (sheltered waters up to force 4).

It’s the job of the International Standards Organization (ISO) to assign this design category to all types of boat, whether propelled by sail, engine or human power.

The RCD requires that each new boat be supplied with an owner’s manual, and this often includes information relating to stability and buoyancy.

Boatbuilders measure displacement to determine an upper limit for weight capacity as well as the maximum number of persons the boat can carry.

New design, lower displacement

British-built Rustler 42 is known for its ocean-going qualities. Photo: Rustler Yachts.

According to Peter Poland, a co-owner of Hunter boats for 30 years, new boats with heavier displacements for their size are rarely seen at boat shows nowadays for one simple reason: they cost more to build.

New cruising yachts tend to follow the form of offshore designs, but for the benefit of increased volume, not stability. Beamier, and often chined, they allow vastly increased living space.

That doesn’t mean heavy displacement yachts are ‘out of date’.

‘Far from it,’ says Poland. ‘The cruising sailor – whether looking for massive or moderate amounts of accommodation below – will find a heavier displacement boat with a lower centre of gravity more forgiving and less twitchy to sail than a lighter boat with a voluminous interior.’

Rustler yachts are known for their seagoing qualities. Adrian Jones, co-owner of the British Boatbuilder, points out that it’s the Rustler’s heavy weather characteristics that make it a popular choice for long-distance cruisers.

‘There is a huge difference between ours and production boats. It’s brilliant that you can get lots of people on the water, but a lot of mainstream boat decisions are made on the cost of production and not what happens when you get hit by a wave, a whale or a gale. We never build down to cost, we build a boat as well as it can be built and hope there are enough people around to buy it.’

Adrian wouldn’t typically have a conversation with a customer about stability and displacement. ‘We never talk about x, y and z. It’s a huge topic and formulas won’t tell you everything you need to know, but motion through the water is the result of all that stuff; how the boat handles.’

Hull development: Is a thicker boat hull stronger?

Marine surveyor Ben Sutcliffe-Davies explains it’s not as simple as that.

“Early GRP boats were laminated to the thickness of wooden boats because that was what the designs were based on; whether half an inch, three quarters or even an inch thick, but if we’re discussing sturdiness, we get into the realms of keel arrangements and hull mouldings too.”

Sutcliffe-Davies explains that with improvements in materials and testing, modern hulls are radically different to those built in the 1970s and 80s. The thinner GRP hulls of today’s production boats easily match the strength of their predecessors.

Early GRP boats were laminated to the thickness of wooden boats, but that’s not necessary today. Photo: Ali Wood.

However, the key difference is that they have an inner and outer hull moulding.

‘From a cost point of view, factories can produce them more quickly, and from a strength point of view, they’re pretty much as strong. But when something goes wrong, there’s nothing to stop those two skins separating – for example, the keel matrix after a grounding. I’ve had yachts grounded where pounding has caused the separation. People will say, ‘that wouldn’t happen with an old boat,’ but you still get damage, just in a different way.”

Ben also points out that production methods used for light displacement yachts have made boating accessible to many more people.

‘In 1970, if you wanted a brand new 40ft yacht you’d be paying around £10,000-£15,000; around three times the value of the average house. These days, you’re looking at less than 1.5 times the current market value.’

This Maxi 84 was built in the 1970s with a very thick laminate. The same strength can be achieved today, but with a lighter construction. Photo: Ali Wood.

Waterline length

A notable change in hull design is that the overall waterline length has increased.

As racing rules put less emphasis on static waterline, upright stems and transoms have developed in the racing world and have been passed down to cruising boats.

The Dufour 37, for example, has a race-boat style near-vertical stem and stern.

The upright stem and transom on the Dufour 37. Photo: Jean-Marie Liot.

In addition to increasing speed potential, additional waterline length wins far more space.

Poland says, ‘I believe many future cruising designs will move closer to vertical stems.’

What type of hull shape gives the best compromise between performance and accommodation, and between light and heavier displacement?

‘Very low freeboard can mean a wetter ride, while high freeboard can add to windage and lift the centre of gravity,’ says Poland.

‘An excessively narrow stern can induce rolling when sailing downwind in a blow, while a fat stern can encourage broaching up-wind in heavy gusts. Narrow overall beam reduces initial stability and space below, while excessive beam means you need to sail the boat flatter. As ever, a sensible compromise can be the answer.’

How heavy is heavy? Calculate your boat’s displacement

How do you know if your boat is light or heavy displacement or somewhere in between?

You can calculate the displacement-to-length ratio, but Ben Sutcliffe-Davies’s advice is to compare the weight of your boat to others of the same size and look at differences in speeds and other parameters, such as its righting capability.

Then, having done that, the best way to know how a boat will handle is simply to go and sail it.

‘I’ve a friend who sails a 50ft Hanse, and he’s always surprised when he steps on board my Sparkman & Stephens that she doesn’t move. Well, she’s not going to, she weighs 13 tonnes!’

For Sutcliffe-Davies, the advantage of having a ‘reassuringly heavy’ boat is that when you get to land’s end and it’s a force 9, you can keep going. But he qualifies:

‘You do need at least a force 3 to get going because of the ballast ratio and everything else.’

ARC 40-footers

Each year, I visit the ARC, and marvel at the range of yachts that take on the 3,000-mile crossing from the Canaries to the Caribbean.

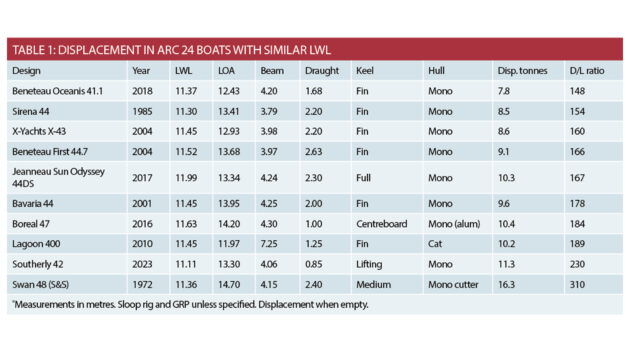

The table below is a snapshot of last year’s entrants with waterlines of 36ft to 39ft.

Note that the figures listed show the displacement without cruising gear On average, skippers added another 15% to 25% to the boat’s weight with gear and provisioning. Photo: Practical Boat Owner.

You can see that displacement varies hugely from the Beneteau Oceanis 41.1 at 7.8 tonnes to the Swan 48 (s&s) at 16.3 tonnes, showing that all sorts of yachts take on ocean sailing (though the comfort and speed with which they do this is considerably different).

That said, most would be described as light displacement cruisers, with the exception of the Southerly (moderate) and Swan 48, which would be classed as heavy displacement.

It’s one thing to compare boats of a similar length, but what about dissimilar yachts?

The key to understanding displacement is knowing how much or little this is in relation to the vessel’s size.

A crude look at the ARC’s entry list will reveal those boats that are on the light side (long waterline and low displacement) and are usually in the racing division – and those on the heavier side, taking part in the cruising division.

Calculating your own boat’s displacement

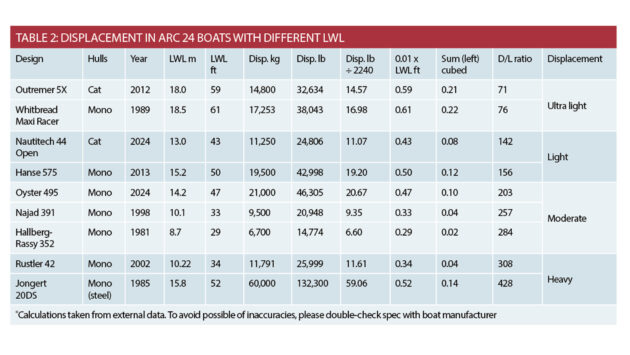

To do it properly, there is a formula you can use which works out the displacement to length ratio, abbreviated as D/L.

It looks a little complicated, but once armed with boat data that’s widely available on the internet, and an application such as google sheets or excel, you can soon have fun comparing different boats.

The formula takes the yacht’s displacement in pounds divided by 2,240. This sum is then divided by a hundredth of the waterline length (measured in feet), cubed.

Displacement lb ÷ 2,240 / (0.01 x lwlft)^3

Alternatively, you can make life easier for yourself and type ‘displacement length ratio’ into google, and find an online calculator to do the sums for you.

The number you get will range from ultra-light displacement (a d/l ratio of less than 100), to light displacement (100 to 200), moderate (200-300) and heavy (above 300).

To put this into practice, I compared a vastly different range of ARC 2024 yachts to see if I could guess where they’d come out.

The rally attracts boats from 33ft to 105ft, dating from the 1970s and sometimes earlier, through to new builds. In the first table (boats of similar size – opposite), I used an online calculator, but in the second table (below), you can see the formulas in use. In fact, there were no surprises.

The 1989 Whitbread Maxi Racer CJ Legend came in as ‘ultra-light’ (76), scoring just higher than the Outremer 5x catamaran (71).

Meanwhile, at the other end of the scale, you have the Rustler 42 (308) and the steel-hulled Jongert 20ds (428).

In between, you have light displacement cruisers such as the Hanse 575 (156) and the moderate displacements ranging from the Oyster 495 (203) to the Hallberg-Rassy 352 (284).

The d/l ratio gives a sense of the boat’s speed potential – the lower the number, the faster the boat, but of course, the trade-off for speed is having less comfortable motion.

Also, if you take a boat with a low d/l ratio and put a cruising payload on her (we’re talking water, fuel, batteries, spare sails, generators, etc), it will have a proportionately bigger impact on performance than putting the same payload on a boat with a higher d/l ratio.

A cruising payload, and adding top-heavy items such as solar arches and satellite equipment to masts, will affect stability. Photo: Ali Wood.

You’d not normally be comparing such boats (unless like me, you get carried away with such things) and it’s worth reiterating that performance ratios work best when comparing boats with similar design features.

For example, in table 2 (overleaf) the Rustler looks slow because its waterline is part of the d/l formula, but boats like this have long overhangs, and when heeled it’s a different story, because the displacement would be higher.

In the example of the S&S Swan 48 in table 1 (below), the overhangs add a whole 10ft – taking the waterline length from 36ft to 46ft.

Forty years ago, most offshore cruising boats had laden d/l ratios well above 400; heavy in terms of sailing capability but very sturdy.

With modern boatbuilding and design trends focussed on volume, overhangs have gone, and d/l ratios have shifted downwards. A brand-new cruiser/racer might therefore be within the 150 to 250 range, an offshore boat 250 to 350.

Modern boatbuilding techniques allow for a much lighter hull. Photo: Ali Wood.

Happily heavy

Heavy displacement yachts are considered more comfortable in rough seas, as the boat tends to go through the tops of the waves rather than over them.

However, multihull sailors will tell you that on a downwind passage their boat rolls far less than a monohull, allowing for games of scrabble and cups of tea while monohull sailors are hanging off galley straps and wedging themselves in – the difference here being in form stability.

A light displacement hull has less wetted surface area, meaning less drag and better acceleration.

Finding the best of both worlds, and within budget, is not straightforward, so it’s interesting to hear what arc sailors had to say about their choice of boat.

PBO Project boat Maximus is a very solidly built Maxi 84. Photo: Ali Wood.

Ask the community: Sailors on their boat’s displacement

Back in 2018, PBO met Mark Thurlow and wife, Gina, on Moody 49 Rum Truffle.

Thurlow told us how much he loved his boat (15 tonnes displacement) because in very heavy weather it holds its line.

Sadly, Rum Truffle was wrecked in 2024 when entering El Salvador under the instructions of the paid pilot, and stripped bare by looters.

In November, Thurlow reported on his gofundme page that the new Rum Truffle is a Lagoon 400 s2.

‘I’ve been lucky to have been able to get back to sea and enjoy the freedom of the seas again,’ he said. ‘Many will be intrigued or even amused by my choice of a catamaran, but I have decided ocean crossings are being traded for cruising the Caribbean.’

Simon Ridley, who we met in 2024, owns a Swan 46 mk 1, with a displacement of 13 tonnes.

Simon Ridley’s Swan 46 Mk 1 displaces 13 tonnes. Photo: Ali Wood.

‘I wanted something bigger and heavier than my Hanse 37, which is why I bought Gertha 5,’ he said. ‘What few people realise is that friction really slows a boat. Gertha 5 has such a sweet hull; half the wetted area of a modern boat which has to drag its flat back through the water… I can do 4 knots in 8 knots of wind, while a lot of boats doing the crossing struggle to get going until the wind reaches 12 knots.’

Irish sailor Eamonn Naughton has sailed many boats, and was impressed by the performance of the Rustler 42 he owns with partner Bridget Mcmahon.

‘The Rustler is a bit heavier and more stable,’ he explained. ‘One of the big things you hear about the arc is that if you have the yankee poled out and goosewing, you get this bad rolling, but actually that wasn’t the case.’

Eamonn Naughton and Bridget McMahon found the ARC+ comfortable in their Rustler 42. Photo: Ali Wood.

James Kenning bought a Swedish Regina 42 for the crossing. ‘Most people haven’t heard of this boat. She’s 43ft but end-to-end with the bowsprit, 46ft. I feel she’s small with a 38ft waterline. She’s the 12th slowest boat in the rally. A bona fide bluewater sailboat with an awful lot of wood; built for comfort and ploughing through heavy seas.’

How boat displacement impacts performance

When looking at performance, you might combine displacement with other variables such as sail area and waterline length. For example, a heavy displacement boat with more sail area could sail just as fast as a light displacement one with less sail area.

While a longer waterline on a low displacement boat has a higher speed potential, it will also be less comfortable in big seas.

For more on this, and understanding form stability, loa, lwl and speed tables, it’s well worth reading the excellent article by øyvind bordal (pbo.co.uk/formulas).

Bordal explains that theoretical hull speed is quite simply the top speed a non-planing boat can sail.

Upwind, the longer the waterline, the faster the boat in displacement mode.

To work out your boat’s theoretical hull speed, simply multiply the square root of the waterline length in metres by 2.43.

For example, if we were to look at the Beneteau in table 1, a lwl of 11.37m has a square root of 3.37. If we multiply this by 2.43, we get a theoretical hull speed of 8.19 knots.

The maximum speed of a boat in displacement mode is limited by the wave it creates.

A planing boat is capable of climbing over its own wave. As soon as the wave created by a displacement boat is as long as the waterline, it can’t go any faster.

Performance will also differ in wind and sea state. In light airs, a boat with a low sail area/displacement ratio won’t tack on a sixpence. Rather, you’d need to bring her around in a wide arc to keep as much of the momentum of the heavy hull as possible.

Built for speed: the brand new Rascal dinghy revealed at this year’s Southampton Boat Show has a 40kg carbon fibre hull. Photo: Ali Wood.

How boat displacement relates to stability

Displacement hulls are often ballasted to increase stability.

A heavy displacement for a boat’s length improves stability, along with other factors such as high ballast ratio, high angle of vanishing stability and modest beam in relation to length.

I experienced this for myself recently when testing the Wayfarer Weekender dinghy.

This Wayfarer Weekender has 60kg of ballast in its centreboard, hugely increasing stability and meaning it’s certified to carry six people. Photo: Dylan Wood.

Unlike its predecessors, this had 60kg of ballast in the centreboard (the equivalent of my own weight) which meant the boat easily handled 20-knot gusts, and our family of five testers. The lighter construction elsewhere helped compensate for the additional weight low down.

A low centre of gravity makes a boat less susceptible to wind and waves than with planing hulls.

Another advantage of a ballasted displacement hull is that if it does capsize it will most likely self-right.

A multihull, on the other hand, will not right after a capsize, so it’s important that the cockpit drains quickly and that you understand the builder’s information on what sails to set in different wind strengths, and how to escape after an inversion.

For more on this, see the RYA’s book titled Stability & Buoyancy.

Ballast ratio

The ballast/displacement ratio – misleadingly shortened to ‘ballast ratio’ – is a useful tool for monohulls as it tells you what percentage of the yacht’s total displacement is ballast.

The formula is ballast divided by displacement multiplied by 100.

The higher the figure, the stiffer (and more stable) the yacht is presumed to be. British boatbuilder rustler yachts, advises that 50% is about the upper limit of a very stiff boat, with 35% being average and 25% regarded as tender (less stable) and unsuitable for ocean voyaging.

‘The big problem with ballast ratio is that it can only be used to compare boats with similar hull shapes and similar keel types,’ points out Rustler’s Adrian Jones.

‘Comparing the ballast ratios of a yacht with a triangular keel and one with a bulb of ballast at the bottom of a deep fin, for example, will be misleading. The keels of our Rustler 33 and 44 are flared at the bottom, putting more of the ballast down low where it’s most effective. They both have high ballast ratios anyway, but if the keel shape were taken into account, the figures would be even higher.’

Form stability

A catamaran has no ballast but high form stability because of its beam. Photo: Ali Wood.

A catamaran, on the other hand, has no ballast but very high form stability because of its wide beam.

The same principle applies to beamy coastal cruisers. With the trend in recent years being to push more volume into boats, the beam gets wider, which in turn increases the form stability, reducing the need for ballast to maintain stiffness.

Increasingly, the ARC has seen more multihull entrants, with now over a third of yachts being multihulls, and 10 of the 13 boats built in 2024 being catamarans (plus one trimaran).

A multihull is not necessarily lighter displacement than a monohull. While, for example, the sporty Outremer 45 catamaran has a displacement of 8.8t, the Leopard 45 catamaran, a popular option for cruising and chartering, displaces 14.9t; more than all but one of the monohulls listed in table 2 (below).

Expert advice from marine surveyor Ben Sutcliffe-Davies

‘A multihull doesn’t have a righting moment. Once you’re upside down that’s it. With any light displacement boat, ideally you will have three reefs in the main and a good storm jib, and understand the risks involved sailing outside the vessel’s category.

The RCD gives clear instructions on the safe parameters of your boat, and you need to be mindful of these.

It comes down to what you want to get out of the boat. If you’re coastal sailing in sensible weather, a production boat; no problem.

Selling up and putting all your money into a boat to go round the world? You need to be looking for something strong, robust and heavy that will take the grunt, no matter what is going on with the weather.’

Sail area to boat displacement ratio

Displacement also works with sail area to give an indication of how your boat will perform. The drive from the sails needs to move a known volume of water (the yacht’s displacement), so this too can be calculated with this formula.

Sail area in ft2 : (Displacement in ft3) ÷ ⅔

The result should come out between 10 and 20, advises rustler yachts. About 15 to 18 is ideal.

Below, and you’ll be under-powered; above, and you’ll be continuously trimming sails and reefing.

Adding weight can decrease the ratio, while increasing sail area can increase it.

Plus, if you add a staysail and yankee, a large overlapping genoa or a code zero, this will increase the sa/d ratio further, so really you need to compare yachts with the same load state and equivalent sails.

Sa/d can also give an indication of the impact of adding extra people and kit. Adding 450kg to a light displacement boat will have a greater effect than it would adding it to a Rustler 42.

ARC sailor David Diaz on heavy weather handling in a light displacement boat

Let’s say you’re lucky and the squall is appearing far from you (and not on top of you, because then it’s game over), the radar will show a big spot, a tower of rain that typically comes with a 50% to 100% increase in wind speed. So if it’s 20 knots, you can expect it to jump to 30, 35, 40, and you have to monitor it.

Squalls move way faster than boats. If you’re heading west and the squall is going west and is in front of you, you’re probably fine, but if it’s behind you, it will catch you up.

There were a few times during the ARC when monster squalls were chasing us, and we decided to turn on the engine to just get the maximum speed out of that area.

There’s no time to go north or south. Rather, you’ve got to consider what sails you have up.

If it’s full main or gennaker or spinnaker you’ll be overpowered and you can’t take them down during the squall. How soon you do this depends on your level of bravery.

Outremer 5X Nuvem Magica. Photo: Ali Wood.

Getting hit by a squall is never good. Even if everything goes well and you just get wind and water, you put a lot of strain on the rigging, and so things break.

Sometimes squalls come with thunderstorms. You get a big dark cloud like a tower, with very heavy wind and rain.

You look at the horizon and you can’t see beyond it. It’s a thick grey that the light doesn’t penetrate. At night, it’s more dangerous because you don’t see it, and you just have to trust your radar that it’s there.

Weather apps can tell you there’s rain, but ultimately not the squalls because it’s a disturbance that happens temporarily. Squalls form and go very quickly. You just have to deal with them. Drink more coffee to stay awake on nightwatch, because it’s dangerous to fall asleep.

The four out of five of us who were competent skippers rotated every three hours at night, but I know that other boats were sailing with just two people, and that’s very hard

with squalls.

Boat displacement in perspective

You can learn a lot from speaking to skippers who’ve owned several boats, and nothing beats sailing as wide a range of yachts as you can.

For example, I know without consulting any diagrams that the GK24 I sailed with my dad had a far lighter length-to-displacement ratio than the long-keel wooden prawner he later swapped it for.

We sailed both over long distances, and in heavy weather. While the former won races and tacked on a sixpence, the latter ploughed through the waves with barely a touch to the tiller.

It’s easy to get carried away with formulas, but dimensions, measurements and ratios are indicators only.

A yacht that works on paper could fail to meet expectations for any number of reasons, from badly rigged sails to build quality.

Weight distribution also has a major effect – especially when kit is installed high up or near the bow or stern – and isn’t factored into these equations.

There are ‘ifs and buts’ with every equation, but they do perform a useful purpose.

Consider your own boat and ask if on paper, she’s as lively or sedate as you hoped?

If the answer is no, when you come to choose your next boat, you can use performance ratios to benchmark it against the one you have… but then you actually need to go and sail it and speak to boat owners and class associations who will be able to tell you everything that the formulas don’t!

Want to read more articles about boat displacement?

A subscription to Practical Boat Owner magazine costs around 40% less than the cover price.

Print and digital editions are available through Magazines Direct – where you can also find the latest deals.

PBO is packed with information to help you get the most from boat ownership – whether sail or power.

-

-

-

- Take your DIY skills to the next level with trusted advice on boat maintenance and repairs

- Impartial, in-depth gear reviews

- Practical cruising tips for making the most of your time afloat

-

-

Follow us on Facebook, Instagram, TikTok and Twitter