Three transatlantic cruisers share valuable lessons about their onboard power setups, their marine battery choices, and where they went wrong.

As any transatlantic sailor will tell you, managing power offshore can be a challenge. No matter how much effort you put into topping up your marine battery system, equipment will break, and even renewable sources can fall foul of weed, and a lack of wind or sunshine.

When the engine failed on Carol Wu’s Hallberg-Rassy, she was 750 miles from land. She had to resort to paper plotting and sailing onto a mooring – thank goodness she was an experienced RYA Yachtmaster.

At the same time, James Kennings’ hydrogenerator was delivering ‘nothing but drag’, and Rasmus Haurum Christensen’s lead-acid batteries had dropped below 12V.

“I made a mistake,” he told PBO. “I just couldn’t keep them charged overnight!’

Better marine battery power management

The good news, however, is that it’s easier to mange power offshore today than ever before, and between solar panels, generators, wind- and hydro-turbines, you should be able to stay charged without ever running your engine.

Testament to this are the hundreds of cruisers who complete the Atlantic Rally for Cruisers (ARC) each year without once logging engine hours.

In the PBO Summer issue, we looked at the boat’s electrical system, and the various options for marine battery management, including the use of shorepower.

However, if you’re planning to be off-grid for days or weeks at a time – whether on a transatlantic rally, or even as a liveaboard – it pays to be self-sufficient.

PBO visited the ARC+ Rally last year to get some tips from cruisers after their three-week Atlantic crossing to see how they managed their batteries.

Power management perspective: James Kenning

James Kenning on Arkyla. Photo: Ali Wood.

Boat: Regina 43, Arkyla

Type of usage: Transatlantic crossing and Caribbean cruising.

In Las Palmas we met James Kenning, an RAF veteran who used his resettlement grant to get his RYA Yachtmaster and charter all over the world, before buying his own yacht Arkyla, a Regina 43.

Since buying the Swedish deck saloon six years ago, he has installed 300W of solar, a Rutland 1200 wind turbine and a Remoran Wave 3 hydrogenerator, which starts generating electricity at 3 knots, making it suitable for smaller boats at lower speeds.

“Even if I’m only doing 5 knots, it will pump out 10A constantly. That will be my powerhouse,” Kenning told PBO. “I don’t have a generator, and I don’t want to start the engine to power up the batteries.”

Arkyla’s domestic bank consists of five 130Ah AGM batteries. This gives a usable capacity of 325Ah, which is 30Ah short of the boat’s worst-case predictions for offshore power draw.

“I’ve tested it all except for the freezer. I’ve never used it. We’ll see how much it drains. I’ve got a Victron battery monitor to tell me the battery state, and a VirCru monitoring system,” he said; the latter being a way to remotely monitor things such as power, bilge levels, location and more from your phone.

Kenning’s 300W of Sunware solar panels are mounted on both the arch and the bimini.

“I think solar efficiency has got a lot better. These rigid panels are very efficient, even on a cloudy day. However, you only get sunshine between 6am and 6pm, and with a downwind rig – either a parasailor or twin headsails – the panels get shaded, which is why my key source of power will be the Ramoren hydrogenerator.”

Kenning has installed flexible solar panels on Arkyla. Photo: Ali Wood.

Kenning shared with us his energy calculations, which he’d conveniently laminated and kept in a folder for his crew to reference.

On a downwind passage with true wind at 15 knots (apparent 8-10 knots), speed over the ground 6 knots (through the water 5 knots), and nine hours of daily sunshine, he estimated he could get 50A from the wind generator, 200A from the hydro-generator and 110A from his solar panels.

James Kenning’s quick tips for managing marine battery power:

- Manually helm on occasion

- Reduce brightness of MFDs

- Turn off freezer for periods at night

- Set radar to timed scans

- Charge phones only during day

- Set cabin fans to timer when sleeping

- Restrict compass light use

- Use other lights only when/where needed

For future cruising, he says he’ll stay with a spread-betting approach of mixed renewables; wind, hydro, and solar, but noting that some cruising grounds will favour some sources over others (eg in the Med, solar is king, in the Caribbean/northern Europe, wind is very valuable. Hydro is really only of use for passage-making).

Arkyla’s low-power induction hob. Photo: James Kenning.

Cruising notes

“Whenever we can during the day, we’ll helm manually,” Kenning told PBO. “It’s far easier than at night, especially if you’re running deep angles with the parasailor. I’ve also got repeating MFDs (multifunction displays) – one at the nav station and one in the cockpit – which I can dim down, and the radar is set to timed scans. I’m not using it for collision avoidance but for seeing squalls, so will need it on, particularly at night.”

He also has two cabin fans, which are very efficient, and can be set on 1,2,4 or 6-hour timers – the key being to have chilled air when trying to sleep.

“I’ve been through the boat and changed everything to LEDS; you would not believe how many lights there are, but the one thing I can’t change is the light in the compass. It’s an old halogen and actually burns quite a few amps, so I turn it off if not needed.”

Having plenty of tankage, Kenning opted not to have the additional power consumption of a watermaker, and though he considered fitting Starlink for sat comms, he rejected that because it draws a ‘hefty 20 amps on start-up’: “Plus you never know what Elon Musk is going to do next with geofencing!”

PBO waved off Arkyla at the start line in Las Palmas, Gran Canaria, as Kenning set sail with almost 100 yachts to Cape Verde, and from there to Grenada on the ARC+ rally. We caught up with him again in Grenada to see how the voyage went.

Arkyla carries solar panels, hydrogenerator and wind generator. Photo: James Kenning.

Hydrogenerator

Sadly, the Remoran Wave 3 developed a terminal fault 24 hours out of Las Palmas.

“It delivered nothing but drag,” reported Kenning. Emails to Remoran in Finland identified that the 6-month-old unit was from a batch with a known corrosion issue in the generator unit.

Fortunately, they were able to send a replacement unit to Mindelo, Cape Verde, but until then, Kenning had to undertake five days of passage-making without having use of the main power source.

To reduce the drain of the autopilot, the crew hand-steered during the day, and at night as well if conditions allowed.

They had to switch off the freezer, by far the biggest power draw on the boat, meaning they had to sacrifice much of the pre-cooked meals.

James Kenning on board Arkyla. Photo: James Kenning.

Thankfully, at the start of the second leg, the new Remoran unit proved itself, pumping out a solid 10Ah day and night much of the time, but when the winds dropped and the boat was only making about 4 knots, this decreased.

Worse was to come: when they encountered large swathes of sargassum weed, the generator prop fouled within 10 minutes of being cleared with a boat hook.

“If weed clogged the prop shaft, we had to stop the boat to lift the unit and clear it out of the water; when travelling above 4-5 knots (and we were regularly at 8+ knots), the force of the water meant that it was impossible to either lift or adjust the generator,” said Kenning.

“After some trial and error, we worked out that if we set the generator at an angle, less weed would accumulate; it was sub-optimal, but we still got good amp-hour returns.”

Solar

On the first leg, Kenning sadly lost the Parasailor sail; it shredded after falling in the ocean at speed.

This meant that for the rest of the crossing, Arkyla had to sail under a twin headsail rig.

“The impact of this was that after about 1400, when the sun was mostly off the bow, the solar panels on the arch and bimini were shielded by the twin headsails,” he said. “I did anticipate this in the original energy budget, but not to the full extent.”

Wind generator

The wind generator contributed to Arkyla’s passage over 20 knots. Photo: James Kenning.

Kenning had always considered the wind generator a bonus if it was to provide any usable power when sailing a downwind passage.

As predicted, at wind speeds of less than 15 knots, very little power was generated. However, if the wind hit 20 knots, which it did for quite a while during the passage, then it did contribute.

“Despite issues, I only had to run the engine (not under load) for a total of 3 hours over the entire 3,000-mile passage. Diligence and flexibility were key to maintaining the power balance despite unexpected issues,” he said.

Key lessons learned:

- The wind generator did not provide significant energy downwind but has been of major benefit in the Caribbean (typically on a reach), and at anchor.

- The hydrogenerator was the best source of renewable power, but was significantly impacted by the sargassum weed. It has not been used in the Caribbean.

- Arkyla had 300W of solar; in future, I’d aim to at least double this. Siting panels is crucial to avoid likely shade during a passage. At anchor in the Caribbean, solar is the main power source.

- It was good that we had a plan to cut down/limit our power draw when needed.

- I had to renew Arkyla’s 650Ah AGM battery bank before the crossing. If I’d had the available funds, I’d have installed lithium cells – unfortunately, they fell off the priority list due to affordability at the time (not so much the batteries, but the power management system also needed).

- Account for all power draws. Helm as much as possible; be considerate in turning off lights. A water pump draws about 6A when operating. We didn’t use the mainsail, so the electric winch wasn’t needed, but would have been a big draw had we been reefing often. Small items such as the instrument panel, PredictWind datahub and Iridium on standby all add up and should not be overlooked.

- Low-power electric fans were invaluable for comfort in the tropics – invest in good ones.

Power management perspective: Carol Wu

Carol Wu and Peter Hopps did the second leg of their transatlantic with no engine and minimal power. Photo: WWC / James Mitchell.

Boat: Hallberg-Rassy 340

Type of usage: Baltic cruising and transatlantic sailing

Hong Kong construction executive Carol Wu swapped corporate life for voyaging around the Baltic after she discovered sailing at Hamble School of Yachting.

With her former instructor and good friend, Peter Hopps, she was one of the few female double-handers to be skippering her own boat, Aria Legra, which at 10.95m (34ft), was also the smallest in the fleet.

When we met her on the pontoons, she was having new batteries installed in the Hallberg-Rassy 340.

“Running a boat is very much like a construction project,” she said. “We’re two days from departure, I just got a new starter battery, and I still don’t have an alternator.”

Marine battery upgrade

She had upgraded from lead-acid to Relion lithium batteries the previous winter, using a Mastervolt charger.

Though she was tempted by a high-output alternator, the boatyard advised her to keep the one that came with the Volvo engine.

“It’s easy to get repaired, so I thought: sensible advice, let’s not go over the top,” she told PBO.

“But I had these beautiful 300Ah lithium batteries all summer, and the alternator just wasn’t putting in the charge it should have. We were banging in about 40Ah, but it should have been around 120Ah. I could run the batteries down on a four-day voyage from Lisbon to Madeira, but I knew something wasn’t right with the charging.

I was pulling my hair out, speaking to all these technicians. They kept saying, ‘why does it matter? You’ll be in a marina in two days and can top up?’ They see a woman in a smallish boat and assume she’s just doing coastal hops!”

Carol Wu’s lithium batteries weren’t charging quickly enough. Photo: WWC / James Mitchell.

It wasn’t until Wu reached Gran Canaria, and spoke to the experienced marine electrician at Rolnautic, that she got the answer she’d known all along.

The alternator, which showed signs of corrosion undetected until Gran Canaria, wasn’t sufficient for the passage.

“The electrician got it right away. He had a different mindset, and understood that I needed to be thinking of battery charging over 3,000 miles not 300!

“With hindsight, I think the original boatyard didn’t understand why I wanted a high-output alternator. I didn’t push it, and it goes back to the whole confidence thing. I thought, ‘they are professionals, lithium is new, but if they think it’s a sufficient setup I believe them.’

The lesson here is that when you ask someone to install a system, be sure they understand your type of sailing. The alternator was OK for coastal hops, but not long distances.”

Wu’s Aria Legra is Hallberg-Rassy 340 hull No8. She chose it deliberately, being a lucky number in Chinese, and the builder has now sold over 60.

A lot of new owners ordered their Hallberg-Rassy with lithium batteries as standard.

Unlike lead acid-batteries, which can suffer from over- or under-charging, lithium batteries should be able to handle higher charge and discharge rates and offer faster charging times compared to Carol’s original deep-cycle batteries.

Expert advice: marine battery choices

The electrician brings the new high output alternator. Photo: Ali Wood.

According to Stuart James at Predator Batteries, you shouldn’t have to make big changes to accommodate lithium.

“Some companies such as Mastervolt might have a separate battery management system, which would need updating, but a drop-in replacement should do the job. You do need to be careful, though, when charging a lithium battery from the engine; don’t have the engine in tickover because the alternator will work flat-out and it’ll get too hot. You have to run the engine at a reasonable speed – at least 1,000rpm – so it’s better to use the generator,” he explained.

“Some people get around this by using a DC to DC charger, which only puts a maximum charge into the battery so it won’t over-work the alternator. A lot of people put these on motor homes, so they can park up for a week, turn the key and let it tick over for an hour, without overheating; the alternator throws out about 100A but it’s only going to put 50A in the battery.”

All hopes were pinned on the new high-output alternator, which arrived just as Wu was in final preparations.

Sadly, however, when the electrician fitted the much-anticipated part it failed to work at all.

There was no charge to the batteries. Already it was Friday night, and the rally was departing Sunday morning.

Fortunately, Wu had saved the original mount, and Rolnautics kindly cleaned and refitted the old alternator.

“Rolnautics said the supplier didn’t include the regulator or mount for the new alternator, so they’d spent a lot of time in the workshop trying to sort that out, which they didn’t charge for, and then they had to put the old one back!”

Solar power

Carol Wu had less solar power than many of the larger ARC yachts. Aria Legra carried a rigid 48W panel and two removable 120W flexible solar panels mounted on the foredeck and companionway.

“They’re a bit floppy, so I can use them if the sea state is OK,” she said.

Like James Kenning, Wu calculated her power requirements beforehand, highlighting that the watermaker drew a hefty 20A – ‘a luxury really as I’m carrying 350lt’ – and the autopilot also consumed a significant amount of power. Instruments drew around 10A and the fridge 1.5-2A. She didn’t have a freezer.

Cruising notes: Carol Wu

Carol Wu and Peter Hopps did the second leg of their transatlantic with no engine and minimal power. Photo: WWC / James Mitchell.

Wu and Hopps set sail on the Sunday morning with the rest of the rally, disappointed to be back with the old alternator, but relieved at least to still have a means of charging the batteries.

They made it to Mindelo, Cape Verde, but not without issue.

Their routine was to run the engine for 40 minutes every two to three hours, on charge mode, not propulsion.

However, on the second leg, 750 miles from Grenada, Wu noticed something of concern during her engine checks.

“There was a lot of black dust in the bilge, and the fan belt wasn’t wearing quite as well. The engine sounded funny on start-up. The belt came off the spindle and everything went crazy! The warning light came on and the alarm sounded. The engine was turning, but there was no way of turning the alternator or cooling it.”

Carol Wu and Peter Hopps took Carol’s Hallberg-Rassy 340 across the Atlantic. Photo: WWC / James Mitchell.

The only means Wu had of topping up the battery was the solar panels, and she didn’t have many. “I don’t have a solar arch or anything like that; just the panels you unfold and put up during the day. We very quickly did the calculations and we worked out we had 72% battery charge at that time. With five days to go, we figured if we did not discharge more than 10% each day we should be OK. But that’s only a fraction of normal power!”

They switched everything off; the autopilot, refrigerator, watermaker, chartplotter, radio. No lights. They wore head torches at night, and after 48 hours turned off all instruments in order to keep the tricolour lit.

At night, they exceeded their ‘ration’ of battery power and during the day were using more power than they could top up with solar.

Low power sends Wu back to old-school sailing

“We switched to very old-fashioned sailing with a compass, but it was OK; that’s how we learned to sail,” said Wu. “We had iPads and iPhones and fully charged battery banks as backups. We’d switch them on quickly to get GPS, and used the handheld radio in the grab bag. When on the helm you couldn’t go to the head or check an instrument without having someone take over. We didn’t even eat meals together.”

Needing the instruments for the approach to Grenada – a passage with outlying rocks – they clung on to whatever battery life they could, and taped a torch to the compass at night.

“The only thing we left on was the tricolour. It was a very interesting experience. Very pure. We weren’t distracted by anything other than sailing. No exchanging WhatsApp photos and talking via Starlink!”

Not all ARC participants carry paper charts these days, but Wu says they couldn’t have done it without them.

“We switched the sat comms on to inform the rally what had happened, but we did all our plotting and pilotage plans on paper charts.”

Amazingly, 40 miles from Grenada they’d managed to maintain 20% battery life. They made contact with ARC Rally Control to coordinate berthing arrangements.

“We figured we might have 5 or 10 minutes’ engine use without it needing to cool, so used it for bursts here and there.”

They were given a large superyacht berth and, demonstrating exceptional Yachtmaster skills, Wu and Hopps managed to sail onto the pontoon, furling the jib a bit at a time until safely moored.

Getting power offshore

There are several ways to charge batteries and get power offshore.

Many cruisers have an inbuilt diesel generator that provides 240V AC, while others carry a small, portable petrol unit. Brands listed among the 24 ARC+ rally crew included Mastervolt, Northstar, Perkins, Cummins Onan, Fischer Panda and Honda.

Several skippers carried Honda’s portable petrol generators, a range which starts at £795 for 1kW, going up to £2,045 for 3.2kW. Units can be linked in parallel to double the output. Simon Ridley, skipper of Swan 46, Gertha 5, commented:

“I have a Honda generator as backup [to my solar]. It’s very noisy but fantastically reliable!”

Renewables are by far the biggest addition to ARC yachts this decade, with cruisers using a combination of solar, wind and hydrogenerators to charge the batteries.

Solar capability ranged from 200W to 2,200W, with boats in the higher range being completely self-sufficient with solar.

Wind generators used by transatlantic cruisers included Silentwind and Rutland 1200, while hydrogenerators included Watt&Sea, Sail-Gen, Duogen (wind and water) and Remoran Wave 3.

Power management perspective: Rasmus Haurum Christensen

Haurum Christensen on Notorious. Photo: Ali Wood.

Boat: Beneteau Oceanis 423, Notorious

Type of usage: Baltic sailing and Atlantic crossing

Rasmus Haurum Christensen’s solar arch caught our attention in Las Palmas.

The impressive stainless steel structure mounted on the stern of Notorious, his Beneteau 423, was recently expanded by Sunny Yacht Services, whose proprietor Svetlyo Dimitrov is a well-known face among yachties, as he cycles to their aid on his homemade folding bike.

Rasmus and his wife, Sarah, decided to do the ARC+ a year earlier. After many years of hesitation, they finally set the date and sold their home and belongings to fund the year-long adventure.

“All we had left were 10 boxes in our parents’ basement,” he said. “You don’t need four winter coats in your loft; all you need are good experiences in life.”

Buying within budget

With a budget of one million Danish kroner (£115,000), they set about buying a bluewater cruiser.

Though drawn to Hallberg-Rassys they realised they didn’t get a lot of boat for their money and instead bought the 2006 Beneteau, which had only one previous owner; a couple who’d sailed it to Tahiti and fitted it out nicely for long-distance cruising.

Before the trip, Rasmus and Sarah replaced the thru-hull fittings, pipework, holding tank and batteries. Being a mechanical engineer, Rasmus enjoyed installing the watermaker, a Schenker Zen 50.

“I loved that, finding out how to fit it all into one small room, and it worked first time, 50lt an hour!”

He decided to buy four new AGM batteries, totalling 560Ah, only they turned out to be lead-acid.

“When we left Denmark, the sun wasn’t as plentiful as we’d hoped. We realised when crossing Biscay that we didn’t have enough power to run the autopilot day and night – that’s a big consumer – and because we wanted to sail double-handed, we decided to install two new solar panels to bring the total to 1000W.”

Rasmus Haurum Christensen shows off his solar frame which tilts the panels to the sun. Photo: Ali Wood.

The additional panels were fitted in parallel in Las Palmas.

To make the most of the solar power, they decided to install them on pivoting mounts. Svetlyo Dimitrov was the man they needed. They gave him the measurements and together they drew up the specification.

“His welding is really good,” said Rasmus, pointing out how Dimitrov had welded the framing together for the new solar expansion. “I think this will be extremely nice when we’re in the Caribbean and do not have to worry so much about power consumption.”

Using the Victron app on his smartphone, Rasmus explained how the arch is rigged up with separate solar controllers so he can monitor the power each one produces. When he lifted the starboard pole to tilt the solar panel directly to the sun, the output doubled.

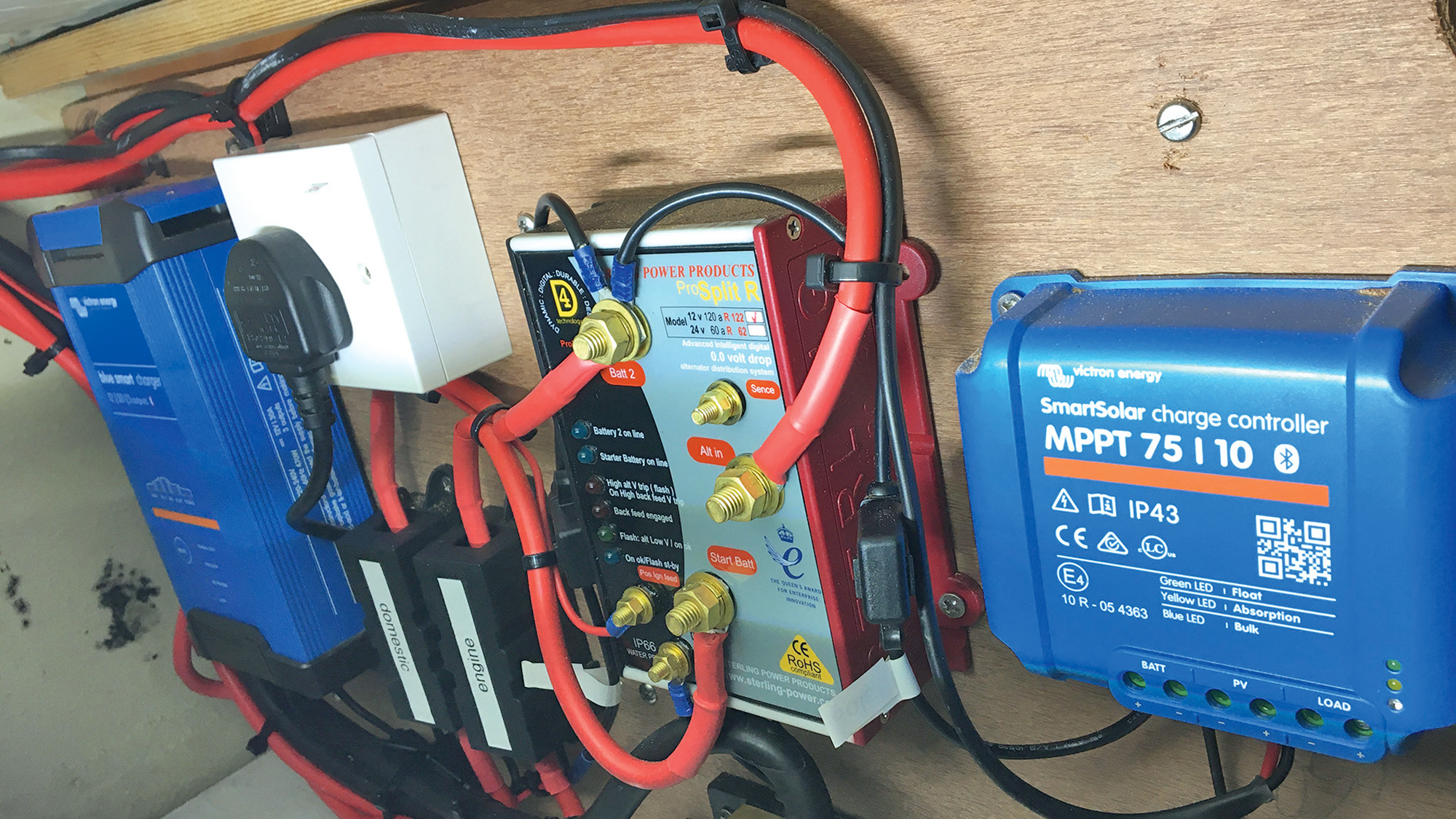

Power management for the solar controllers. Photo: Ali Wood.

“You don’t need as many panels,” he said. “It’s also quite cool, I think. We basically have wings on our boat.”

Cruising notes: Rasmus

Rasmus was delighted when we caught up with him in Grenada.

“It was a very good decision to have the solar frame,” he said. “On an east to west passage, the sun was always on the port side so we kept the port panel at 45°, and the starboard one at 0°.”

Tucked up safely in Port Louis Marina, the crew had switched to shore power and lowered the panels but Rasmus said they’d tilt them once again at anchor.

The passage didn’t completely go to plan, however. They started out sailing wing-on-wing with an old mainsail and poled-out genoa, but after ripping the mainsail had to switch to using two headsails.

The other minor issue was the batteries.

“I’ve regretted buying lead-acid. I thought I had bought AGM,” said Rasmus. “Fortunately, we had so much solar it was OK, but in the morning, before the sun got up, the batteries were at 11.9V. They shouldn’t dip below 11.5V for the health of the batteries.”

The crew of Notorious made sure the boat was well stocked with supplies. Photo: Ali Wood.

Expert comment: PBO’s engine expert Stu Davies points out that AGM batteries would not have been any better at holding charge. There might be another issue at play on passage (see further down).

The good news is that neither the mainsail breakage or the batteries was enough to take the shine off the voyage (or the solar panels!), and the crew very much enjoyed their fishing and cooking.

“We caught a blue marlin that weighed 20kg,” said Rasmus. “It served six people for three meals. We’ve still got the tail hanging up in the boat.

“Everybody chipped in, and we had pancakes, bread, all kinds of pasta dishes. To avoid cockroach eggs boarding the boat, we removed the labels from the tins, and this made for some surprising dishes such as ‘pasta with three cans’, which could have been anything – beans, tomatoes, mushrooms. We ate like kings. I’ve never had such good food.”

Some further good news: as PBO went to press, Rasmus reported that the batteries coped well for four months without shorepower in the Caribbean, and on the return sail via the northern Atlantic (Saint Martin to the Azores in 19 days), the solar arch comfortably withstood the 48-knot gusts.

The expert take on marine battery power management

Stu Davies, engine expert, has a background in engineering in the coal and oil industries, working on everything from small engines to massive turbines.

Case one: James Kenning

James did the energy power audit well, worked out what he needed, then put it into practice.

The combined wind/water generator is a good tool, but has its drawbacks when crossing the Atlantic, as he found out. Wind generation isn’t very good when going downwind, and the sargassum weed is the other drawback.

Solar arches etc can be contaminated by shade from the sails.

One of my more experienced friends (eight Atlantic crossings) taught me the best place to have solar panels is on the handrails, so you can easily adjust the angle to maximise the harvest, and they’re easily stowable in marinas.

Running the engine once a day is a good way to go as well. It provides a solid power base and also, dare I say it, heats the domestic water!

Case two: Carol Wu

Fitting a high output alternator is not a magic fix, as Carol found out, and especially as all the parts for it weren’t supplied.

This, combined with her fitting lithium batteries without a charging regime to suit them, probably caused all her issues.

She has had various yards and techs telling her conflicting advice on her needs. The consensus nowadays is that if drop-in lithiums are fitted, then they should be used as the house bank, a separate lead-acid battery should be used for the starter and engine charging regime, and a suitably sized battery-to-battery 12V charging system put in.

The engine alternator should charge the engine lead-acid battery, and the battery-to-battery charging system should run off that to charge the lithium bank. The lead-acid battery acts as a buffer to protect the alternator.

Charging lithiums directly from an alternator is a big no-no. They can absorb so much power that they can overwhelm the alternator and burn it out.

The issue with the black dust is a symptom of using the alternator directly to charge the lithiums. The alternator was putting out a lot of charge, the load on the alternator caused by this was making the belt slip, hence the dust and eventually the failure of the belt.

Gates makes a toothed format belt which I use: this type drives better due to its better flexibility, and it slips less.

Also, just because she has a 120A alternator fitted, does not mean that it should put out 120A. As I said before, the alternator charges at the rate the batteries require, ie their state of charge.

Case three: Rasmus Haurum Christensen

AGM batteries are, very basically, lead-acid batteries in another electrolyte format.

You can find good comparisons of them both online but personally, for me, the extra cost of AGM isn’t worth it for the tiny advantages they bring, and of course, they still only deliver roughly the same amount of power as a flooded marine battery, ie half the stated capacity.

He says that his batteries didn’t hold charge overnight. His 560Ah of batteries should give him around 260Ah usable capacity plus 1,000W of solar. The solar should have been more than enough during daylight hours.

*Rasmus responds: “This was only when on passage with many electrical consumers such as radar, plotter, autopilot, freezer, Starlink, watermaker, etc. Our marine battery capacity was on the low side with the amount of power-consuming equipment on board.”

A beginner’s guide to managing marine battery power

Word to the wise: always keep an eye on your marine battery. Last summer, I hired a flybridge cruiser on…

Boat battery care: the do’s and the don’ts

Stuart James of Predator Batteries shares his expert tips for achieving optimum battery performance on board your boat

Industry insight: lithium marine batteries and other power options

A lot of people are wondering whether to switch to lithium marine batteries, but don’t actually know what they should…

Lithium iron phosphate batteries: myths BUSTED!

Duncan Kent looks into the latest developments, regulations and myths that have arisen since lithium-ion batteries were introduced

Want to read more articles on managing power?

A subscription to Practical Boat Owner magazine costs around 40% less than the cover price.

Print and digital editions are available through Magazines Direct – where you can also find the latest deals.

PBO is packed with information to help you get the most from boat ownership – whether sail or power.

-

-

-

- Take your DIY skills to the next level with trusted advice on boat maintenance and repairs

- Impartial, in-depth gear reviews

- Practical cruising tips for making the most of your time afloat

-

-

Follow us on Facebook, Instagram, TikTok and Twitter