Stranded 200 miles offshore in big seas without a rudder is every sailor’s nightmare. The crew of Quokka found a solution and sailed to safety, reports Louay Habib

Just after midnight, the Grand Soleil 43 Trustmarque Quokka left the River Hamble in the UK, bound for Malta and the Middle Sea Race via Cascais, Portugal. She was skippered by her owner, Peter Rutter, a former Commodore of the Royal Ocean Racing Club, with three highly experienced crew: Graham Moody, Malcolm McEwen and Scott Dawson.

After Malta, Quokka was bound for the Canaries, where she would be joined by her race crew in a bid to win her class in the ARC transatlantic rally, reaching St Lucia in time for Christmas.

Quokka was in ocean-going trim, prepared for commercial MCA approval and equipped with a large quantity of water and food, a water-maker and a full tank of diesel with 70 litres in a back-up container: but 200 miles off the French coast, disaster struck.

Quokka’s rudder snapped, leaving the crew with no way of steering. It was nearly five days before the stricken yacht limped into La Trinité in Brittany. The crew managed to get to safety without assistance, but their solution to the problem was far from easy; and a number of lessons can be learnt.

Scott Dawson recalls what happened and how the crew dealt with the dire situation they found themselves in.

Screen grab from Quokka‘s Yellowbrick Tracker, showing where the rudder broke and when the jury rudder was fitted

‘Before we left the UK, we knew that we would hit rough conditions in the Bay of Biscay. We made good speed across the English Channel, and we were at Ushant 24 hours later. As the forecast low-pressure system from the west began to arrive, we headed west to get onto the downwind side of it. Expecting 25-30 knots, we put two reefs in the main.

‘At about 2230, we were in Biscay, 200 miles from the nearest land. I was on the helm. The wind was gusting 40 knots, and we considered dropping the main altogether. We could hold course, but it was more comfortable to run with the wind, and we were at about 160º TWA (True Wind Angle).

Steering the boat was very comfortable, but the sea state was building; at that point, the waves were 3 or 4m high. We were running down a wave at around 11 knots when there was a big crack, and I felt something hit the bottom of the hull. The wheel had no resistance at all. To my horror, I realised we’d lost the rudder.’

Here’s how Graham Moody recalls the disastrous moment.

‘Scotty was on the wheel, Peter in the cockpit, myself in the pit getting halyards and reef lines organised and Malcolm below. Scotty shouted: “The rudder’s gone!” The boat rounded up, Peter grabbed the second wheel, thinking the rudder had just stalled, and Scotty ran forward, telling me to drop the jib. Malcolm arrived on deck to be hit by the mainsheet. Somehow we dropped the main, then went below to assess the situation.’

Scott continues, ‘Peter was concerned on two counts: firstly, had the rudder hit an underwater object and had the damage caused a major hole in the hull? Secondly, we were not under control in a major shipping channel, with four vessels in sight. He asked Malcolm to put out a Mayday’.

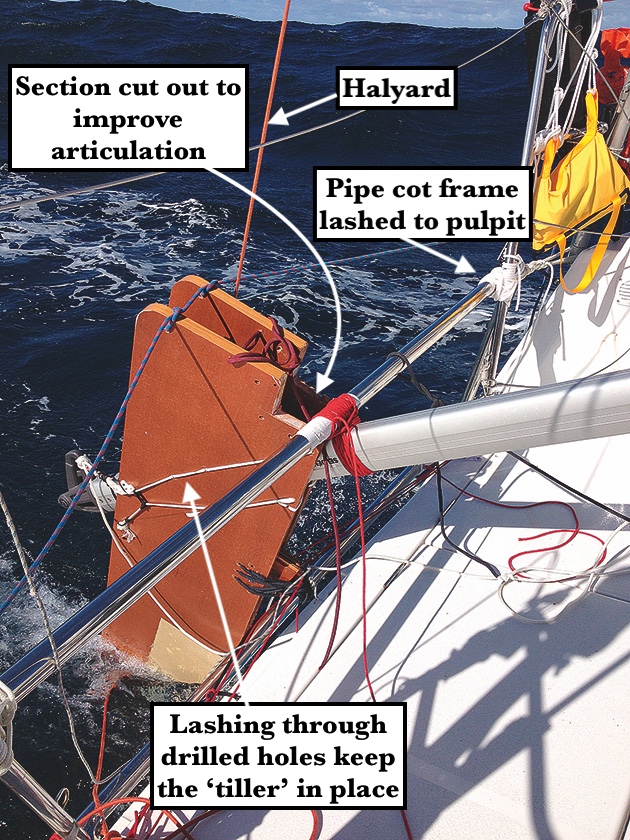

The jury rudder soon after installation. The red halyard was left attached in case the assembly broke loose from the boat. Credit: Scott Dawson

Malcolm McEwen recounts the communication to shore:

‘I went below and called a Mayday on Ch16 VHF. After two or three tries, I was answered by Captain Pilling on cargo vessel Tinsdal about 8NM south of us. He offered to stand by, and also offered to call the Falmouth Rescue Co-ordination centre and its French equivalent, CROSS Etel.

‘Some time had now gone by, and it was clear that we were taking very little water. Tinsdal was still standing by, but we all agreed that a transfer would be risky and would mean the loss of the boat: we were prepared to stay on board. I thanked Captain Pilling and released him to carry on his voyage. In a satellite phone call with Falmouth coastguard, we agreed we were now not in “grave and imminent danger”.

We were drifting away from the shipping lanes, and they asked if we might reduce our Mayday to a pan-pan, which I agreed to do, and I put out an all-stations call on VHF Ch 16. The French CROSS Etel rescue service now had our satellite number, so they called us and requested a two-hourly condition and position report. Thereafter, they rang us every two hours on the dot.’

Scott describes the scene that followed.

‘We were side-on to the waves, falling backwards down them, rolling badly. Water was finding its way into the boat via the stern cockpit lockers and collecting in the bilge.

We were pumping for 20 minutes every two hours. We had plenty of fuel to keep the engine, the pumps and the communication systems going, but we prepared for the worst: if we needed to abandon ship, both of our MCA-approved grab bags and our liferafts were ready to go. It took quite a while to believe that we were going to be OK.

Although the boat was rolling violently, at no stage did we think we were going to roll over. It was the middle of the night and we could not really assess anything until it was light: we knew we were not in immediate danger, so we decided to get some sort of rest.

We set up a watch system of a man sitting in the hatchway with a big torch and a collision flare. Our main concern was being hit by a ship, but the radar reflector was already up the mast, and we kept a good watch. The motion was pretty uncomfortable, so we all took seasickness tablets, and they knocked me out for about four hours.

‘At dawn, we managed to make a cup of tea and eat some muesli bars: the wind had dropped to 30 knots. We kept our position logged using the electronics, and saw that we were drifting eastwards at about a knot and were now outside the shipping lanes.

‘Morale was desperately low. We were all absolutely physically exhausted. Peter had been on the phone and had been quoted €20,000 salvage, but with every hour we were getting nearer to land: the longer we kept going, the less expensive salvage would be.

‘However, we knew that between us and the safety of port was the continental shelf, where the depth suddenly switches from 4,500m to 150m. This could mean huge waves, capable of breaking a boat with no means of steering.

And what if the wind changed, blowing us offshore? We were in 5m waves now, but if it was blowing when we got to the shelf, they would be a lot bigger and steeper.

‘That first morning, CROSS Etel sent a small plane out to check on us. It was very reassuring to know that the French rescue service was there to advise and support us. Maybe under their watchful eye, we’d be able to get ourselves, somehow, to land.

‘We had time to think about what to do; the shelf was 70 miles away, three days at our current speed of drift. We knew we needed to find some way of steering the boat well before then. We were all still very tired: just walking down below was a huge effort, and the motion on deck was far worse, but we started to think about a plan.

‘Quokka has an emergency tiller, but without a rudder, it was useless. First, we tried a spinnaker pole, but Quokka has an open transom, and there was nothing to lash it onto, and we could not get the pole deep enough into the water. With the engine ticking over or on full power, we just went round in circles. Morale was even lower than before, but that night Graham Moody started scribbling in his pad. He used to be a yacht builder and designer, so if anyone could come up with a solution, he could.

The next morning, he said, “I’ve got it! I think I know what to do!” ‘Peter thought Graham’s rudder design looked promising. We all set to work scavenging two cabin doors to make the rudder, the vang to act as a tiller, and other bits of metal and rope from around the boat. Then we could start to build the structure down below in the saloon.

‘It took a long time, and the constant rolling didn’t help. Building the rudder was like assembling a kitchen flat-pack on a bouncy castle with the local Scout troop jumping up and down! But our morale was right up: We made a proper lunch, and the activity and sense that we had a plan really lifted us.

The continental shelf was now only 40 miles away, and we were praying that our plan would work. ‘Once we’d finished building the rudder, we had a frustrating overnight wait before the sea calmed down enough for us to be able to hoist it up over the transom and let it carefully down into the water.

A view of the bottom rudder-to-frame attachment of the jury rudder. Sandwiched between the doors are sections of bunk base with a V-cut into the centre piece to move the articulation point forward. Credit: Scott Dawson

‘To our delight, we got it fixed into place. At first, with the engine on ticker, we tried to see if we could just hold a course. It worked! We were able to steer the boat: we were all smiling.

‘We put the storm jib up, and with the engine ticking over, we made 5-6 knots. Even better, the sail balanced the boat, and the motion finally became normal again after nearly three days and nights of violent rolling. At last, we were in a much better situation.

‘Then our satellite phone suddenly stopped working. With no ships in VHF range, we lost contact with the coastguard and our worried families. When Etel couldn’t raise us on their two-hourly call, they sent the plane out again, and we asked the crew to relay a message to the sat phone provider. Peter’s wife, meanwhile, discovered that the company had suspended service due to high usage!

We were soon reconnected. ‘It was difficult to learn how to drive the boat. The sea state was still 4m or so, and the natural way to come down the waves was to traverse them, but this didn’t work with our makeshift rudder, as it would put a lot of force on it.

Surfing dead downwind would put less strain on the rudder, but would make Quokka prone to rounding up. All of this took a lot of concentration; we were changing drivers every 30 minutes and split into teams of two: one would steer while the other kept a close eye on the rudder, watching for lashings coming loose.

With land almost in sight, Quokka motors gently to minimise strain on the jury rudder. Note the

satcom dome and Q flag. Credit: Scott Dawson

‘We arrived at the continental shelf at night, and as a precaution we took down the forestall and stopped steering, and just drifted until dawn. It was still blowing 20 knots as we crossed into the shallow water, but the angles of the waves meant that that sea state was not as bad as it could have been.

We knew this was the last big hurdle. At first light we started sailing again and headed for Belle-Ile – the nearest land, which was 40 miles away. Spirits onboard were high as we realised that we should reach land before dark, so we’d just spent our last night at sea.

‘We were heading for Belle-Ile because, once we got into the lee of the island, the sea would be flatter and we’d only be 20 miles out – a comfortable distance for the coastguard to come and get us if need be. By late evening we reached Belle-Ile and turned north for La Trinite-sur-Mer.

Five miles out, we dropped sail and motored in. We steering into La Trinite four-and-a-half days after the rudder had snapped. Although the coastguard and local shipping were on alert, we made it our mission to reach safety unassisted.

‘When we moored up, I have to say that there was a feeling of great pride as well as the realisation that during the entire ordeal we had remained calm; there was not a single angry word between us, and we took our time to sort out a solution that worked.

Time was on our side and we used that wisely, but I have learnt a hell of a lot from the experience. Probably the biggest lesson I have learnt is that no matter how difficult things get, there is always a way out.

How We Made The Jury Rudder

Graham Moody conceived the jury steering assembly and explains how the crew worked together to build it.

On my off-watch, I lay in my bunk and thought to myself, ‘I’m a boatbuilder: surely I can make a boat steer’. I looked round the saloon and found inspiration in the cabin doors.

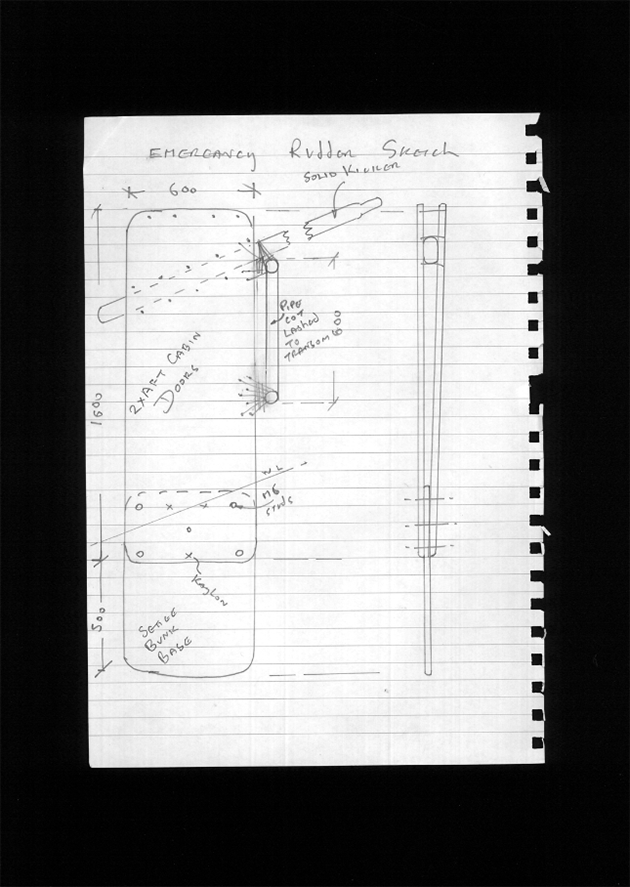

They were a good shape for a rudder, but we’d have to destroy them in the process. I got up and went to the chart table, and started to draw a rudder and tiller made out of various bits of the rigging and interior. Two cabin doors would make a solid rudder structure if sandwiched either side of the vang, which would make a sturdy tiller.

A copy of Graham Moody’s design sketch for the jury rudder. About the only change from the plan was mounting the tiller below rather than above the frame. Credit: Scott Dawson

We could add depth to the rudder by bolting two wooden settee bases to the bottom of the doors to make an underwater area of 750 x 600mm. When I showed my sketch to the others, they were enthusiastic.

Peter, the owner, agreed I could cannibalise the boat, and Scott came up with the idea of lashing the frame of a pipecot berth across the open transom to create mounting points. We set to work building the steering system in the saloon, diagonally across the space, with the tiller poking into an aft cabin.

(Doing it on deck would have been impossible in those rolling seas.) Then we thought, ‘can we get it out, or have we built ourselves into a hole?’ I went aft with the galley chopping board to mark out the angle between the rudder and the tiller so that the tiller would pass over the steering pedestals.

It would have been too high if we had left the steering wheels on, so we decided we’d have to take them off. Then we found that the one tool we didn’t have was a socket that would fit the wheel hub nut.

But Scott had the brainwave of converting one of the hole saws into a box spanner by driving it onto the nut to get the shape, then using mole grips.

Lots Of Lashings

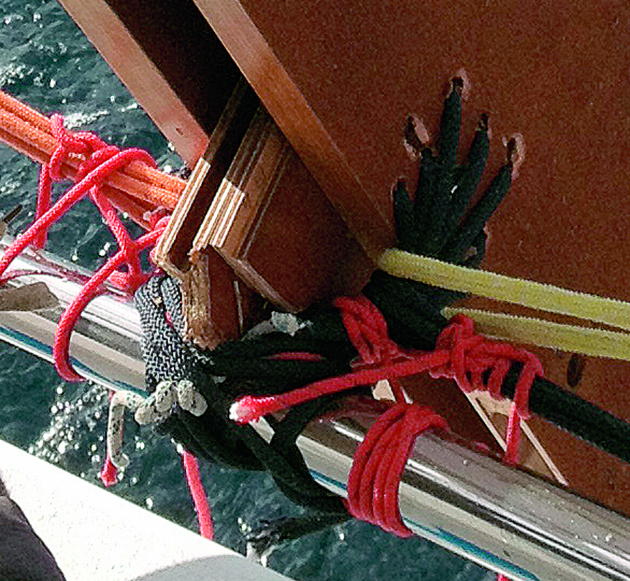

The tiller was ‘stitched’ into position between the doors. I had already realised, because it was me who’d packed all the spares, that we didn’t have enough bolts to make the structure, and we’d have to find an alternative.

Luckily, Malcolm is very good at ropework, and we had a rechargeable electric drill, so we could make holes and thread rope fastenings through them. In the end, more than half the assembly was lashed.

Fortunately, we had large amounts of small-diameter Dyneema/Spectra line, so we didn’t get to the point of cutting down spare sheets and guys. Lots of turns on a smaller diameter rope are much easier to put on and get tight than larger diameter.

When we’d finished making the assembly, we were still working out how to attach it to the frame with some kind of articulating joint. We looked at blocks and other fittings on the boat, but in the end, I designed a wooden V-shaped piece supported by plenty of lashings.

We didn’t know if it would work or last, but lashing turned out to be a good solution as it affords plenty of shock absorption. We had to wait until the wind moderated before we could attempt to fit it.

Safely in port, the jury rudder was disassembled. The crew used two doors, three bunk bases – one on the bottom of the rudder, the others cut up for parts – five bolts, seven large self-tappers and about 200m of rope. Credit: Scott Dawson

The rudder was left overnight in the cockpit as we prayed for a weather window the next day. The morning dawned fair, so we prepared for the challenging operation of getting the rudder firmly in place while being tossed around by the rolling sea.

We built the rudder as per the drawing, but then, for two reasons, we dropped the blade deeper in the water. Firstly, I realised there wouldn’t be enough immersed area, and secondly, we moved the forward edge down as it was getting wide and would reduce articulation. Then, to improve articulation further, we cut a section out of the doors so that the frame would not bind on them.

We pre-made the upper and lower lashings so that when we pulled the rudder into place, we only had to pull on two strings in each one to firm it up into position. We hoisted it up over the stern on a halyard led via the backstay and held it at 90° above the water while we lashed the top loosely, at the same time pre-reeving all the lower lashings.

Then came the challenge, given that wood floats, of lowering the blade gently into the water. We’d rigged two lines from the bottom of the rudder to a pair of cockpit winches.

As we slowly let go of the halyard, we tightened on the bottom lines and pulled in the lower lashings. For lateral alignment of the lower lashing, we pulled on it from each side using ropes round the port and starboard pushpit bases.

The two steering wheels were removed to make room for the ‘tiller’. Credit: Scott Dawson

Later, we gave it more grunt using two 6:1 handybillies normally used for the genoa staysail. Every three or four hours, we checked every bit of the structure. Lashings needed tightening, and we added extra lashings over time.

The only minor problem was the starboard pushpit foot breaking loose under the strain from the cot frame, so we had to lash this foot to nearby fittings. We made steady progress, but not long after we started off, the wind got up, and we found it difficult to keep on course when it got up to 20 knots.

We decided that in anything over 20 knots we wouldn’t risk over-stressing the rudder, but would let it swing – we didn’t lash it firmly as we were beam-on to wind and sea, and the risk of damage would be greater. We tried trailing drogues, but they didn’t hold us more than 45° into the wind off the bow. We gave it up as it wasn’t too uncomfortable down below.

Although running repairs were needed every few hours, at no time did we feel we were going to lose it. I became concerned that the bottom part of the rudder, being only half-inch ply, would snap off, so we added limiting lines to restrict articulation to around 15° each side of the centreline.

Twelve-Point Turn!

About halfway in towards La Trinité, the wind was only about 5 knots, and Peter suggested we try getting in and docking ourselves. That’s what we did! We could only move the rudder 15° each side of centre, and the rudder was only 1⁄3rd normal size, so it was difficult to steer, especially backwards.

We must have done something like a 12-point turn in the tide in the river so we could dock head to stream, but in fact, we ended up due to drift, docking downtide on an inside berth. Once we’d landed, we took our jury steering to bits and restored its parts to their former locations.

The doors could have been rehung, but with holes and corners cut out, they wouldn’t quite match the Grand Soleil’s stylish interior, so new ones are on order. However, the bunk frame and vang are now back in use undamaged, and the lower part of the rudder is back in use as settee bases, autographed for posterity by the four crew.

What We Learned

- You never know when something might break. Our rudder had passed structural tests just before we left the UK.

- Always go to sea well supplied with food, water and fuel. You never know how long you might be on your own. Tools and spares can save your boat.

- Our set of tools included an electric drill. You can never have too much thin, strong rope aboard!

- An emergency tiller system is useless without a rudder. Work out how to steer your boat with an emergency rudder: consider a solution to this.

- We had a satellite phone but ran out of credit, and the airtime supplier cut us off! There should be an emergency number available all the time.

- Falmouth and Etel coastguard centres have our heartfelt thanks. Their support was vital to our safe return.

- Many chartplotters give the position of the cursor rather than the vessel’s position. The font size and colour are exactly the same: this is confusing when you are in a stressful situation.

- Our Yellowbrick tracker reassured our friends and family that we were moving towards land.

- A simple emergency rudder system would be like-for-like, fitting a substitute rudder through the cassette in the deck.

Although the rudder had snapped off, the bottom of the stock was still in place, so we couldn’t use the cassette. A way of pushing out the broken part, then sliding in the replacement, would be useful.

Want to read more articles like 200 miles offshore with no rudder: How four sailors built a jury rudder from cabin doors?

A subscription to Practical Boat Owner magazine costs around 40% less than the cover price.

Print and digital editions are available through Magazines Direct – where you can also find the latest deals.

PBO is packed with information to help you get the most from boat ownership – whether sail or power.

-

-

-

- Take your DIY skills to the next level with trusted advice on boat maintenance and repairs

- Impartial, in-depth gear reviews

- Practical cruising tips for making the most of your time afloat

-

-

Follow us on Facebook, Instagram, TikTok and Twitter