Microyacht adventurer Andrew Bedwell tells Katy Stickland how he resurrected his Atlantic ocean world record challenge

“The strops on the crane broke and Big C was dropped onto the concrete; it was smashed, causing irreparable damage,” says Andrew Bedwell.

“I was a bumbling mess, and everything came out: the grief about my father, who had died two days before I had set out. But then I decided that enough was enough; I had to redo it, create a version 2. That night, sitting down in a restaurant, probably not sure whether to use the serviette for tears or for drawing, I drew up a new boat, and 70% of that design is in the boat today.”

Microyacht adventurer Andrew Bedwell is no quitter. Even when his dream of crossing the Atlantic lay shattered on the harbour wall in Newfoundland, he dusted himself down and got back up again, with a vision for Big C V2. Two-and-a-half years later and he is deep in sea trials and troubleshooting faults to make sure he is ready for May and the start of the biggest challenge of his life – a 1,900-mile crossing of the Atlantic, from St John’s in Newfoundland to cross the finish line for the record off the western point of Ireland.

Big C V2 is built from seam-welded aluminium, 5mm thick at the keel and hull and 3mm for the topsides. Credit: Katy Stickland

Andrew Bedwell on designing the perfect boat

To get to this stage has taken “an awful lot of man-hours”. After sketching out the initial design on the back of a napkin, Bedwell used masking tape on his kitchen floor to mark out the design; he needed to check that he could stretch out his legs in the vessel. Next, he used cardboard boxes to build a life-size model of the boat, marking out hatches, the mast and where the batteries would go; he now needed to find a naval architect.

Jérôme Delaunay was chosen because he “just got it and was used to designing very small, unusual vessels. He later told me it was the hardest vessel he’s ever had to design,” said Bedwell, who is a Jester Baltimore Challenge veteran, and has sailed around Britain and from Whitehaven in Cumbria to Iceland and into the Arctic Circle aboard his sparse 6.5m (21ft) Mini Transat, Blue One.

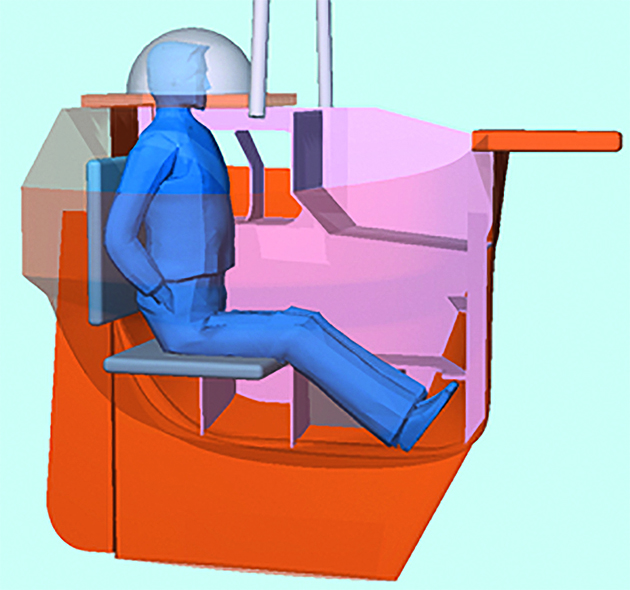

There will be enough space for Andrew Bedwell to stretch out his legs while seated on Big C V2. Credit: Jérôme Delaunay

Starting from scratch has allowed Andrew Bedwell to design the boat he wants for the Atlantic challenge. The previous Big C was designed and built by Liverpudlian sailor Tom McNally, who set the record for the smallest boat to cross the Atlantic in 1993, before it was broken by the current record holder Hugo Vihlen. McNally had planned to challenge for the record again with Big C, but died from cancer in 2017.

Big C was built out of GRP with a foam core and was just over 1m/3ft 2in long; each section was 25mm thick. The new version is aluminium; 5mm of aluminium for the keel and hull and 3mm for the topsides. This has resulted in an extra 90mm of living and storage space inside. At 1.4m/4ft 6in wide, this allows 6ft-tall Bedwell to stretch out his legs which he couldn’t do in V1.

Big C V2 under construction. Credit: Andrew Bedwell

Andrew Bedwell will not reveal any other measurements, but Father’s Day, which Vihlen sailed to claim the record, is 1.63m/5ft 4in long, so it will be smaller than that. There are other differences too. V1’s bulb keel has gone, replaced with an encapsulated 115kg lead keel secured with 25mm diameter keel bolts, which run through the boat and can be adjusted from inside the structure, if needed.

The shape has also changed, with the original two pods on V1, which worked as outrigger stabilisers (like a trimaran), now incorporated into V2’s design. Due to being so short, Big C heels forward, creating drag.

Each section of the boat was tabbed together before welding. Credit: Andrew Bedwell

“The faster you go, the further Big C leans, which gives you more and more drag, slowing us down. The architect has spent hundreds of hours doing CFD modelling, and the result is V2 is more hydrodynamically shaped. Our top speed to date is 3.7 knots, which even the architect did not think was possible!”

Solar panels are now permanently mounted on the hull, and the main watertight 10mm polycarbonate domed hatch is now complemented by an 8mm polycarbonate washboard which can be lightly pressurised to strengthen the dome hatch further, “effectively pre-stressing the structure and preventing deformation or collapse when there is plenty of white water.”

Two 50W solar panels provide much of the power to Big C V2. Credit: Katy Stickland

The hull, including all of the navigation and power systems, rigs and mast, weighs 250kg and in total the boat is designed to carry 550kg. The directional dorade vents at the front of the boat are also sealable from the inside.

The dorade vents can be closed from the inside to prevent water ingress. Credit: Katy Stickland

“V2 is basically like a buoy when everything’s sealed down. I can literally seal the hatch, sit in the harness, and ride out any storm while she gets thrown around. That is why we have made the boat quite tender because we want her to roll. It might seem odd, but if you’ve got a boat that is absolutely set vertically with a massive keel on the bottom, a big wave could come in, hit the rig and break the rig, so we will roll; it will just be like a great fairground ride.”

How Andrew Bedwell will sail Big C downwind

The V2’s rig is made with an aluminium A-frame with one central furling system and two outriggers. This flies two 10oz Dacron sails which are deeply cut and easily reefed. Bedwell has fitted ‘fuses’ to every backstay, outrigger and shroud so they will be the weak point rather than the Dyneema rigging. This also makes it easier to carry spares, rather than rolls of Dyneema.

An aluminium A-frame is the heart of the rig, with a central furling system for twin Dacron sails. Credit: Katy Stickland

“Everything has a fuse on it, so it can be easily replaced. All the shackles are the same, so I only need a few shackles to solve a lot of the problems, and then with some Dyneema on board I can repair anything. I’ve got a couple of blocks and a couple of low-friction rings, and that is about it. If all of that fails and I need more spares, then I will have a bigger problem to solve,” explained Bedwell.

Rubber U-joints act as shock absorbers for the outriggers. Credit: Katy Stickland

Rubber U-joints from a windsurf rig are fitted to the end of the outriggers where they connect to the hull to help take any shock loading away from the boat or allow it to be absorbed into the structure. The rig has also been designed for minimal chafe, and the Dyneema has a Technora cover where there is any risk of chafe, such as from the bow drogue. Stainless steel tubes have been machined and fitted where the rigging enters the boat to reduce friction and protect it from wear. The sails can also be furled as tightly as possible.

Due to limited space on board, there are fuses throughout the rig which can be easily replaced with minimal material. Credit: Katy Stickland

“We’ve used a very modified Harken Hi-load furler and have machined up a sleeve to go inside it, so it gives us a lot more pressure so we can furl tighter. That means we can manage the furl better, and we should, as we have two sails, have two sheets going around the sails with the webbing and Dyneema material on the sail protecting it from any damage.”

If boat repairs are needed, his tool kit will include a Knipex set of pliers, Phillips and straight head screwdrivers and two Allan keys as well as nuts, threads and screws. Two eyes have been fitted on the back of the boat for two aft drogues, which will also be used for emergency steering if the rudder fails.

Stainless steel tubes reduce friction on the lines. Credit: Katy Stickland

Four pintals support the rudder, as well as one solid tubular pin which runs throughout its length; a trim tab will be on the blade’s trailing edge. This trim tab will be connected to a fixed vane, which will work similarly to a junk rig, so the size of the vane can be adjusted depending on the conditions.

Big C V2’s keel will eventually be encapsulated. Credit: Katy Stickland

Inside the boat, there’s a navigation station just below the hatch opening, with an Icom M510 AIS transponder, a sleep timer, an Icom M10 VHF radio and AIS receiver, USB charger and switches to turn on the aircraft strobe light on the mast head. There is also a Garmin handheld chartplotter; handheld VHF and Navionics on Bedwell’s phone will be the backup system.

Powering up

The navigation station includes a sleep timer, AIS, VHF radio, and can all run independently on batteries. Credit: Katy Stickland

Power is provided via two Victron batteries, a 20Ah Absorbent Glass Mat (AGM) and a 20Ah lithium, both in sealed compartments, which are supported by two 50W solar panels.

“Lithium can’t take a charge in cold temperatures so we have an AGM lead-acid battery next to it, which will allow some heat to be generated when the AGM is in use. In theory, this should allow us to use the lithium battery quicker, rather than just waiting for the ambient temperature to rise.”

With the domed hatch closed, a further 8mm washboard can be put in place and then the living compartment can be pressurised to strengthen the hatch. Credit: Katy Stickland

Almost every part of the interior has been carpeted for insulation, although Bedwell will be wearing a dry suit most of the time. The boat will also carry a Katadyn Survivor 35 manual watermaker, a spare water desalinator, a small anchor and a paddle.

Storms at sea

Bedwell and his team are expecting that he will sail through five storms during the crossing, which he hopes will be completed in less than 90 days. Once he leaves St John’s in May, Bedwell will sail Big C V2 down the coast and into the Gulf Stream.

“Generally, the worst conditions are around the Grand Banks area. But as we’ve all known in the last 10 years, weather systems have changed significantly, so we are expecting five storms; we’ve planned for as much as we can.”

Aft, two eyes have been fitted for stern drogues, which will help control speed and direction. Left you can see the flap (below, which prevents sea water from entering Andrew Bedwell’s emergency breathing system. Credit: Katy Stickland

Storm tactics will be furling the sails as tightly as possible, shutting the dorade vents and then closing the hatch and fitting the additional polycarbonate washboard. Sealed inside, Bedwell will have 40 minutes of oxygen. To combat rising carbon dioxide levels, he has installed a simple but clever snorkel sealing system, which will also remove condensation. He can breathe in and out via the snorkel, with his breath vented out aft of the boat via a small opening (which is where his bilge pump can also be fitted).

The flap will prevent water from entering the emergency breathing system on board. Credit: Katy Stickland

Bedwell says he has volunteers prepared to rescue him if the worst were to happen, but ultimately, the plan is to stay with Big C. “I haven’t got a liferaft on board. The reason is that the vessel is so solid that she is my survival capsule. So whatever I’d be getting into would potentially, probably be weaker than Big C.”

“There are a few given things in life – you will be born and you will die, but in the middle there is a dash, and I want to fill that dash with as many adventures as I possibly can.”

Tiny yacht, big record

1964 John Riding sailed his 3.81m/12ft 6in sloop, Sea Egg, from Plymouth, UK, to Bermuda

1965 Robert Manry sailed his 4.10m/13ft 6in Old Town Whitecap Tinkerbelle from Falmouth, Massachusetts, to Falmouth in Cornwall, UK

1968 Hugo Vihlen crossed from Casablanca, Morocco, to Florida aboard 1.80m/5ft 11in April Fool

1983 Tom McClean crossed from St John’s, Newfoundland, to Oporto, Portugal aboard 2.3m/7ft 9in Giltspur

1993 Tom McNally crossed from Lisbon, Portugal, to Fort Lauderdale in Florida aboard his 1.63m/5ft 4½in boat, Vera Hugh

1993 Hugo Vihlen is the current Guinness Book of Records holder for the smallest boat to cross the Atlantic, sailing from Newfoundland to Falmouth, Cornwall, in 106 days aboard 1.62m/5ft 3in Father’s Day

Big C Atlantic Challenge ends in disaster as the 1m boat is smashed while being lifted from the water

Andrew Bedwell's Big C Atlantic Challenge is over, after his 1m boat was smashed while being lifted from the water

Why I’m crossing the Atlantic in the world’s smallest yacht

What’s inspired this world record microyacht attempt? I’ve always dreamed of breaking the world record for the smallest vessel to…

What do you eat on a transatlantic when your boat’s only 1m long?

When you’re aiming for a solo world record, saving space is a priority… and when you’re in a 1m yacht,…

How to prepare a small boat for a big offshore sailing adventure: Top tips from Jester Challenge sailors

The art of sailing a small boat single-handed for long periods has been perfected by Jester Challenge sailors. Jake Kavanagh…

Want to read more articles like The World’s Smallest Boat? How Andrew Bedwell built his 100cm boat to sail across the Atlantic?

A subscription to Practical Boat Owner magazine costs around 40% less than the cover price.

Print and digital editions are available through Magazines Direct – where you can also find the latest deals.

PBO is packed with information to help you get the most from boat ownership – whether sail or power.

-

-

-

- Take your DIY skills to the next level with trusted advice on boat maintenance and repairs

- Impartial, in-depth gear reviews

- Practical cruising tips for making the most of your time afloat

-

-

Follow us on Facebook, Instagram, TikTok and Twitter