Jam jars for nav lights and kerb stones for ballast! Mike Coates recalls his astonishment when asked to survey a new motorboat

Back in the 1970s I used to do a small amount of yacht surveying while working in a boat yard. Insurance companies in those days didn’t require qualifications or third-party liability cover other than for the surveyor to be ‘qualified by experience’.

I received a call from one of the insurance companies I dealt with, asking for a survey within the next four weeks on a new motoryacht, before they’d continue with insuring it. This was slightly irregular as insurance companies were fighting for new clients in this relatively new sector of their business. Few questions were asked about a new vessel; they were all too ready to accept your business!

When I saw it I understood why. I thought I’d seen it all as far as poor construction goes, but this was to be a real eye opener! We’d actually recently launched the motorboat at the owner’s request. It had arrived by road and was a new-build, freshly completed by a yard whose forte was steel canal boats: this was their first foray into fitting out glass hulls. The 24-footer was based on a renowned hull and deck moulded by a company with a good reputation for producing yacht and motorboat designs aimed at the rapidly expanding home-build market.

She was in a mud berth, so rather than tramping out through the mud at low water to start my preliminary inspection (I’d lift the boat later to inspect the propeller shaft, and rudder, etc), I waited until the tide had flooded then rowed out to take a look.

My first impression was a neat and tidy vessel – as it should be given it was only four weeks old – which would no doubt give lot of pleasure to its new owner. I did decide, however, the hull form would look more appropriate on an inland waterway rather than on the North Sea.

I always carried with me a pre-typed form, which I normally worked through to ensure I didn’t miss anything important. Today was no exception. As usual I started in the bow.

The first item I noticed was the anchor and chain. Lifting the anchor out of the locker I noted a large piece of concrete too heavy for me to lift had been dropped into the bottom to aid fore/aft trim. Resembling a porcupine, it had been cut from a piece of reinforced concrete and painted to cover the ends of the steel reinforcing rods that stuck out and were already starting to bleed red rust.

The anchor had been a fabricated copy resembling a flat spade anchor. Unfortunately the constructor hadn’t fitted the pivoting blades with any means of them completely inverting. In the event the anchor dug in, the blades would almost certainly invert as soon as any load was placed on them, releasing it from the ground.

The chain, a sturdy 3⁄8in (10mm) link appeared to be a piece of used hardened lifting chain. Laid out, it had been given several coats of red oxide primer before being given a coat of silver paint. Alarmingly it was less than 5m long; I doubted it was even sufficient for a canal, let alone the much deeper North Sea. Despite there being a hawse pipe there was no way to deploy the anchor other than by opening the forehatch to throw the anchor over the side.

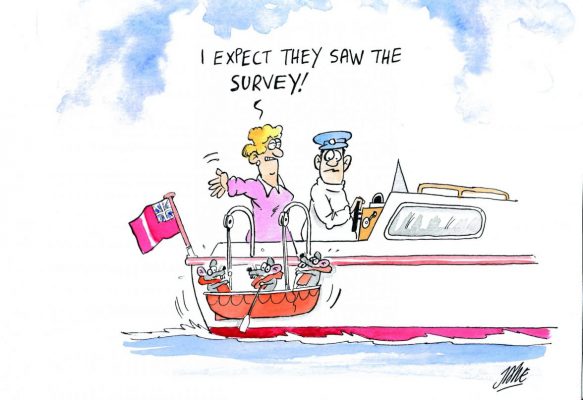

Cartoon by Jake Kavanagh

The forehatch itself had been constructed from a hardwood frame glazed with standard domestic 5mm (3⁄16in) glass, neither toughened nor laminated. It did have some thin timber strips optimistically serving as protection bars; highly dangerous from the point of any one standing on it from the deck and it shattering.

The portholes in the cabin topsides were of similar construction with timber surrounds holding the glass in place.

Working aft a marine toilet was set midships partially enclosed by a lifting ply cover set between the forward vee berth. The first thing I noticed was that the inlet and outlet pipes disappeared behind the bulkhead. I could only presume they were plumbed directly from the seacock with no anti-syphon loop in either. I couldn’t see the seacocks themselves as they had been hidden behind the built in woodwork. Opening a wheel valve that protruded from the surrounding woodwork produced a steady trickle of water into the bowl – more than sufficient to sink the boat in less than 24 hours should anyone inadvertently forget to close the valve after use!

Conti Board disaster

Inspection of the woodwork forming the forward vee berth showed, with some surprise, that it had been constructed from Conti Board. For those of you not familiar with this material it was a popular DIY material used in the 1970s for DIY cupboards, etc. It was manufactured from veneered chip board; a totally unsuitable material for marine use. In its short life it had started to swell at the edges at an alarming rate where it had drawn moisture from the bilge.

Having found this major defect, I decided to abandon my checklist pending an inspection of some of the major structural items. A couple of the main structural bulkheads were also found to be Conti Board, bonded onto the hull on one side only using the minimal amount of glassfibre mat and resin, the visible sides not hidden by lockers, had been neatly bonded using a fillet of silicone. Again the bottoms of the bulkheads had started to swell alarmingly.

Lifting the floorboards in the cockpit made my hair stand on end. The boat had been ballasted using concrete kerb stones, none of which had been secured.

Witness marks on the bilge paint showed where they had been sliding back and forth across the boat when the boat had been at sea.

Movement of the starboard ballast had been restricted by a standard piece of copper domestic plumbing pipe bonded through the hull to form an engine cooling water inlet. There was no valve on the inlet pipe meaning the engine was permanently connected to the seawater.

Similarly, the outlet for the cooling water returned to the sea via a similar piece of copper pipe bonded into the hull. Either of these pipes could have been sheared off by a sliding kerb stone resulting in a fairly rapid sinking.

The engine beds bonded into the hull by the moulders had been slotted to take flexible engine mounts so the engine sat level fore and aft. To meet up with the angle of the prop shaft, a universal joint system from a motor vehicle front axle drive shaft had been modified and fitted to connect it to the prop shaft.

Aghast by the galley

Two batteries sat in the bilge, one each side of the engine with no means of restraint. One was dedicated to engine starting, the other to the domestics.

The port side had a lead from the positive terminal to a through-hull bolt; presumably an anode. Similarly the starboard had its negative terminal connected to a through-hull bolt: possibly some new way of electrically killing any potential fouling – or perhaps just flattening the batteries?

The diesel tank for the ex-Transit van engine consisted of a large plastic jerry can with a feed and return through the filler cap. When getting low on fuel it had to be assumed – as there was no deck filler – the whole can would be lifted out of its stowage and taken for filling.

The galley was little better. A non-gimballed two-burner gas ring without flame failure device was fed via a flexible hose to a large gas bottle and regulator in its own dedicated locker below and to one side of the cooker.

An attempt had been made to ensure any gas leakage would be vented overboard by a lower through-hull fitting though the side of the locker forming the vent. Unfortunately the vent was below the waterline. The locker always had water in it to the level of the sea outside ensuring it was useless as a vent!

It was noted when checking the bilge, the steering was a push/pull rod system which was by a manufacturer I’d not seen before. Initially, I couldn’t understand why it should have 22 turns of the wheel from lock to lock – far too slow a response to allow the boat to be quickly manoeuvred if required. Examination of the steering system revealed the reason; the mechanism consisted of a modified shop window blind operating system to give the fore/aft push/pull required to the rudder steering arm. Ingenious but totally unsuitable for what it was being used!

Not fit for purpose

A cursory look at the electrics showed domestic 240V switches had been used throughout, as had a domestic fuse box. No further inspection of the electrics were carried out, except for the navigation lights – which turned out to be inverted jam jars, the lids used to mount a bulb holder, the interior being painted to the appropriate colour.

I didn’t bother to go any further with the survey. Needless to say I had to report ‘this vessel was not fit for purpose and should not under any circumstances be used, especially at sea.’

The owner was up in arms about it, and the builders said they’d make good any remedial work necessary. Taking my advice, he insisted he should get his money back and walk away from it. The boat was duly lifted out and collected by the builders. I received court threats from the builders about my report. I told them to get on with it as any court hearing would no doubt be very detrimental to their business.

Remember next time you buy a boat: all that glistens is not gold. Seek the advice of a professional surveyor, who should find any hidden defects. It may save a whole lot of heartache later.

About the author

Mike Coates was Practical Boat Owner’s much-loved rigging expert for over 20 years. He passed away on 11 December and will be sadly missed by all the team at PBO and the many readers whose problems he’s solved over the years.

Mike Coates was Practical Boat Owner’s much-loved rigging expert for over 20 years. He passed away on 11 December and will be sadly missed by all the team at PBO and the many readers whose problems he’s solved over the years.