Perceived wisdom is that if you fall overboard, staying tethered to the boat will keep you safe. But is that the case? PBO’s test team conduct some trials… with sobering results

The tragic drowning of the skipper of the Reflex 38 Lion 15 miles south of Selsey Bill in 2011 shocked the sailing world. But the subsequent Marine Accident Investigation Branch (MAIB) report was truly chilling because it emerged that Mr Christopher Reddish (47) had done everything by the book. He was wearing a lifejacket and he was clipped on with a tether, or safety, line – but when he went overboard from the foredeck on a dark night he was dead by the time the crew could recover him.

The man overboard drill that crews generally practise, and which mirrors the RYA syllabus, deals almost exclusively with recovering an untethered casualty from the water – mostly involving a fender floating free, retrieved with a stab from a boathook. The ability to return to a free-floating MOB and pick him up successfully is an important skill to have, but it doesn’t help us recover someone who is still attached the boat. As Christopher Reddish’s death proved, this could have tragic consequences.

Excerpt from the Lion MAIB report:

“At 0027 on 18 June 2011, the No1 genoa was being passed into the cockpit when it was noticed that the skipper had fallen over the port side near the bow. The skipper was still connected to the starboard jackline by his 1.8m-long tether. The mainsheet was immediately slackened and the foresail released, which slowed the yacht’s speed to 1.5 knots around 3 minutes after the skipper fell overboard.

The skipper was found in the water with his lifejacket inflated and the lifejacket bladder over his head, obscuring part of his face. His tether was still connected to the starboard jackline and had passed over the spinnaker pole and under the lower guardwire on the port side. The team managed to raise the skipper’s head above water, but there was no reaction from him. Attempts to clear the skipper’s airways and check for signs of life proved very difficult because of the obstructing lifejacket bladder.

The recovery team fought hard to keep the skipper’s head above water… however, he repeatedly slipped under the surface. After 8-9 minutes of frustrated effort… they clipped the spinnaker halyard directly to the skipper’s tether. The skipper was lifted partially clear of the water and was grabbed as his lifejacket started to slip up his body.

It took the crew 16 minutes to recover the skipper to the deck, where he was pronounced dead by a consultant cardiologist who was one of the crew.”

Speed towing trials

To find out what it is like to lose and recover a tethered MOB, PBO’s test team headed into the Solent on a Sigma 38, Festina Lente, with a stiff 25-knot south-easterly breeze whipping up a big spring tide to a nasty chop. Our ‘casualty’ was Fred, a realistic, weighted rescue dummy wearing a lifejacket. Once in the water Fred would act in much the same way as an incapacitated sailor. First up, we wanted to see how the dummy coped with being towed through the water, so we motored at a series of fixed speeds. Here, he’s attached via a standard, long tether to the jackstay, passing under the guardwires.

2 Knots

At two knots, Fred’s head stays just above water and he’s towed gently along on his back. Even with the boat heeling a little and dunking him lower in the water, his face stays clear.

3 Knots

At three knots, things begin to get more dangerous. Fred’s head is half-immersed, with water cascading around it – although his nose is clear of the surface in waves.

4 Knots

At four knots, Fred’s being towed on his side. His face is being forced underwater and he’s beginning to spin slowly.

Five Knots

At five knots, the boat is approaching hull speed and digging itself a trench. The tight tether pulls his torso up, while his head is forced underwater.

6 Knots

At six knots Fred was being pulled along stomach (harness attachment point) first, with his head beginning to act as an aquaplane, driving the body underwater. It’s hard to know how different this would be with a conscious casualty, but it’s a fair bet that it would be almost impossible to keep your head above water.

Tether Length

To investigate the difference between tether lengths, we towed Fred from both the windward and leeward sides, using first a long and then a short tether, passing under the guardwire as a worst-case scenario. His tether was clipped to the webbing jackstay running along the deck.

What happened with the standard, 1.8m-long tether

Most of us use a long tether when moving around the deck for the simple reason that it allows for greater movement and flexibility. However, things proved to be seriously dangerous when being dragged through the water with it.

On the windward side, Fred dangled close to the hull. His position was in the ‘trough’ of the boat’s quarterwave, and he was repeatedly smashed into the hull by the waves.

On the leeward side, things were even worse. The long tether allowed him to be swept back into the boat’s boiling quarter-wake and, with the boat nearing hull speed, he was almost entirely submerged, with the lifejacket unable to keep his head out of the water. The flare of the yacht’s stern threatened to knock him out.

What happened with the short, 0.8m-long tether

With a short tether, Fred is pulled clear of the water. This was especially true if he was on the windward side, where the short tether kept him entirely clear of the water, with his legs just touching the surface. This won’t be comfortable, but will at least keep you clear of immediate danger until you can be rescued.

On the leeward side, things were different. At six knots, Fred was being towed close to the hull, crashing against it. At anything over two knots the boat’s wake and the movement of the waves conspired to force the water up and around his head and face, which would make breathing impossible.

What we learned

- The MAIB Lion report recommends the use of a short tether to ensure you don’t go overboard in the first place. If you are unlucky enough to go over, we found that a short tether will keep you out of the water on the windward side, but still places you underwater on the leeward side.

- It would therefore seem sensible to always clip on to the windward jackstay with a short tether, to give yourself the best possible chance of remaining on board if you fall to leeward, or clear of the water if you fall to windward, so that the crew can attempt to recover you.

- From our photos above you can see that if you are in the water and tethered to the boat, it’s the speed that is dangerous, regardless of tether length. Because of this, the crew’s first priority must be to stop the boat. Once they’ve done that, you may have a better chance of survival.

How to save a tethered MOB – crash stop!

For Fred’s head to stay above water, our tests showed that the boat’s speed needs to be reduced to no more than two knots.

No real person would be able to withstand for long the sort of immersion that we put the dummy through. We consulted a sailing GP, who suggested that in fact no one could cope with any more than about a minute of submersion when being buffeted on the end of a tether, so that means the crew needs to slow the boat’s speed down to two knots or less as soon as a tethered casualty falls overboard – ideally, in less than a minute.

In other words, you need to perform a controlled crash stop, to keep boatspeed down and the MOB alive while the crew makes the boat safe for the victim’s recovery.

There are several ways to do this. We tried three:

1 Heaving to in a hurry

Going into a tack

Time to 2kt: 33s, to stop: 44s

A Sigma 38 is a powerful beast and required a brief period head-to-wind to slow down sufficiently to heave to properly. We found the main needed to be fully eased to stop her from powering up and returning to her original tack. The tack had the advantage of slowing the speed and, if the casualty was tethered on what had been the leeward side, he now ended up on the windward side following the tack – on a short tether, the boat’s heel would keep him clear of the water.

While on a reach

Time: 1m 30 sec to 3.4 knots min

We also tried pulling the jib to windward and dumping the mainsheet while sailing on a reach to see if that would stop the boat as well as a tack-heave to: our time to stop shows it wasn’t. The only situation where this manoeuvre might be an advantage would be if the MOB fell over the windward side and you wanted to heave to so as to recover him – which would be better on the windward side.

Recovery

The boat lay happily beam on to wind and waves, and with the helm lashed, the motion became easy. The problem was in the recovery. It depends which side the MOB is tethered to, but the obvious side to recover him is to leeward – the freeboard is lower and the hull provides a lee to stop the waves affecting the MOB. But the flogging mainsail and boom was extremely dangerous and made recovery to leeward a non-starter.

2 Head to wind, sails down

Time to 2kt: 30s, to stop: 2 min

Going head to wind is another way of losing speed rapidly, and it makes sense to immediately drop the sails – flogging sailcloth makes any kind of verbal communication and manoeuvring difficult. How fast you can do this depends on the setup. On the day we had a working jib hoisted up a headfoil, and a mainsail without sliders – making dropping them more time-consuming, despite a crew that was ready and waiting. We went head to wind to reduce the speed instantly, put the engine on and then dropped the sails. A roller-furling headsail and mainsail with stack-pack would make the whole process quicker and safer.

We found that having halyards flaked and ready, not neatly coiled, was extremely important. With sails down, recovery could be started within two minutes.

Recovery

Recovery was much easier with no sails up. While the boat was no longer heeling, and the freeboard was therefore higher on the leeward side, communication was much improved and there was no danger to the crew working on deck.

3 Jib poled out, crash stop

Time to 2kts: 22s, to stop 43s

This was the real eye-opener of the day. Many people, myself previously included, might think that having a jib poled out on a run would increase the time taken to stop the boat in an MOB situation; but instead it makes heaving to a piece of cake. All you need to do is luff up, head to wind. The poled-out jib acts as a parachute and stops the boat dead within one boatlength – a fraction of the time experienced by any other method. Once the way was off the boat and the mainsheet eased, she sat peacefully hove to, beam on to the wind.

Recovery

Recovery while the boat is hove to was still problematic on the leeward side due to the boom, but the windward side, while higher, was safe and clear from hazards.The ‘slick’ created by the side-slipping boat not only kept the waves down but also stopped Fred from being slammed into the hull.

Recovery under way

Time to stop: n/a

Trying to get the casualty back aboard while under way was a non-starter.

We struggled to keep Fred’s head and body above water while the boat was moving at four knots, and the crew were at risk of being dragged in too. It’s obvious you’ll need to reduce speed before anyone will be able to assist a casualty in getting back aboard.

Short-handed

We tried the various techniques with a double-handed crew – in other words, with one in

the water and one still safely aboard. It worked best with the helm heading up close to head to wind to kill the speed, then engaging the autopilot to keep the breeze at 20° off the bow, while the crew worked their way forward, furling the jib and dropping the main as quickly as they could.

We found that heaving to before dropping sails wasted time as the lack of steerage way confused the autopilot. It was better to go close to head to wind and remove sail – as long as halyards were flaked and ready to run – as it then made recovery much easier than if hove to.

But heaving to is still a good option if, for some reason, you can’t get the sails down quickly enough.

Spinnakers

Sailing with a spinnaker up, it could conceivably take some time to stop the boat, especially with

an inexperienced crew or in a lot of breeze. There is an RORC method for dropping the spinnaker in a hurry: it involves performing a very quick tack while dropping the kite, which is then quickly retrieved by the foredeck crew. We hope to try this in a forthcoming issue to see if it’s as dangerous as it sounds.

What we found

Of our three methods for stopping in a hurry, sails down is the safest option, and should be considered the default course of action.

But if this is dangerous or difficult in the circumstances – if the boat would roll heavily in a seaway, for instance – then heaving to and starting the recovery process quickly on the windward side is a good course of action. If sailing downwind, a crash stop is essential to slow the boat down, but is something you should practise.

VERDICT

The test team was pretty subdued the evening following these tests. The results convinced us that staying on board in the first place has to be the number one priority: a short tether might be infuriatingly inconvenient when moving around the deck, but if you go overboard there’s a better chance of being held clear of the water than if you are wearing a longer tether.

If someone does go overboard while clipped on, the crew’s first reaction must be to stop the boat as soon as possible, before attempting recovery.

The shorter the tether, the better. The MAIB Lion report states: ‘Had the skipper used one of the short 800mm tethers… he would not have gone overboard.’

The key point, borne out by our tests, is that a tether should prevent you from falling overboard at all. A short one is far more likely to do this – and improves the experience a little should you end up in the water. Use the shortest tether available that still lets you move around in safety. If using a longer line, consider clipping on near the boat’s centreline, especially when working in the cockpit, to make it physically impossible to fall overboard.

We found the tether clips almost impossible to disconnect under load. Consider buying a webbing cutter to keep on your lifejacket belt, so you can cut the line if you are in danger of being drowned. It needs to be to hand and you need to know how to use it.

If someone does fall overboard, the whole crew need to be fully trained and ready to react instantly. Even a minute’s delay could kill the MOB.

Real-life situations

- The skipper of a Contessa 32 was wearing a lifejacket and clipped on when washed overboard in 2011 while entering port and handing the mainsail. The crew were unable to get him back on board, but he was successfully recovered by lifeboat.

- In 2010, Prue Nash was washed overboard in the

Irish Sea at night. Towed at speed behind the Bénéteau 40.7, she was unable to breathe or release her tether, but managed to wriggle free from her lifejacket/harness. She survived by treading water for two hours in the dark until being rescued by another yacht. - The skipper of a 36ft (11m) yacht was washed overboard in 2003 while clipped on. The yacht was approaching harbour and the crew were unable to recover him. The yacht surfed onto the beach and broke up, but the skipper survived with cracked ribs.

- In 2007, a wave carried one of four crew on the foredeck of a yacht overboard. He was clipped on with a long lifeline, but despite the yacht being hove-to the crew couldn’t haul him on deck and he slipped from his lifejacket into the water. He was then recovered safely. The lifejacket waist strap and thigh straps were found to have released during recovery.

Video: Tethers on trial

How to recover a MOB that's still attached to your boat

Second Briton dies in Clipper Round the World Race

The death of businesswoman Sarah Young follows that of London paramedic Andrew Ashman, who was knocked unconscious in September on…

Clipper Race crew suffers suspected broken ribs

Clipper Race crew member Michael Gaskin, from the West Midlands, sustained suspected broken ribs after he fell by the helming…

Hitch horror and trailer trauma – Dave Selby’s latest podcast

Dave Selby asks 'Why must boat trailers be such a drag?' in his latest column published in Practical Boat Owner…

What to pack in a grab bag

No one wants to abandon ship, but a grab bag of essentials can make a short stay in a liferaft…

Clipper Race crew knocked down by a tornado

Thousands are expected to flock to London's St Katharine Docks this Saturday to welcome the Clipper fleet home

Warning to wear lifejackets after boat sinks

Four rescued seconds before their speedboat sinks in the Thames

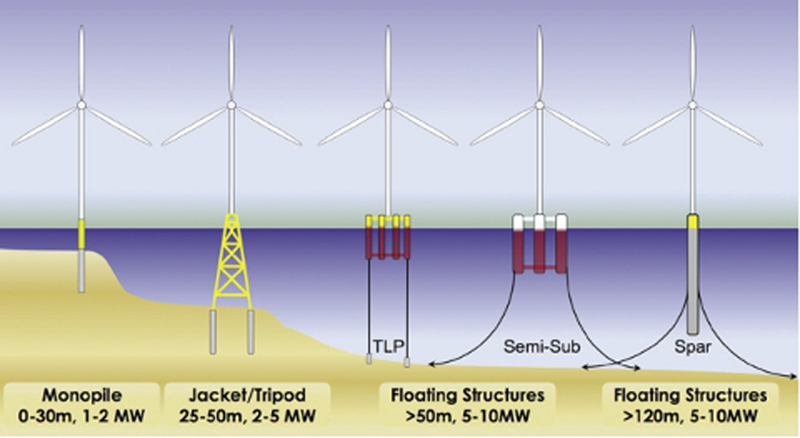

Concern about floating wind turbines

RYA fears that the new offshore wind energy plans will impact boaters

Yachtsmen recovered after falling overboard

Man overboard rescue helped by a life jacket

Video: TeamO lifejacket on test

Does this revolutionary lifejacket increase an MOB's chances of survival?

Bryan Chong’s letter in full

See PBO July for more on the deaths of five sailors in California

MAIB report – Morgan Cup fatality, June 2011

Skipper of Lion drowned during race

Sailor dies in RORC race

Man overboard tragedy off Cowes