Daily progress over the summer break should see a finished hull, deck and rig at the show ready for auction. Rob Melotti reports

Some real head-scratching work has been going on this month as the pace picks up in advance of Southampton Boat Show. Although the Secret 20 is a kit boat for which most of the elements are supplied almost ready to fit together, there are a few intricate parts that are left to the builder’s own creative ability. Boatbuilders refer to these bits as ‘the fun’ apparently!

Regular readers will recall that work started on the Secret 20 project boat at PBO’s office and workshop in Poole back in 2016. When the magazine was moved to new premises in late 2017, work stopped for nearly a year before the boat was donated to Gosport-based charity Oarsome Chance (OC), where a team of professional boatbuilders has gradually made headway on finishing the boat.

Now named Harvey, in memory of a much-loved OC volunteer who passed away earlier this year, the PBO Project Boat is going to be auctioned to the highest bidder during Southampton Boat Show, with all proceeds going to support the charity’s work with young people excluded (or at risk of exclusion) from mainstream education.

Harvey has gone from a pile of ply to an (almost) finished vessel

Filled and faired, the hull awaits more treatment

In addition to ‘the fun’ sections, the last of the elements that did come supplied with the kit have been prepared and dry-fitted – many of which are the foundations for securing the rig. The Samson Post and the coachroof beams and stringers have all been cut, shaped, planed and fitted; the layers of ply and hardwood that make up the rudder have been epoxied to the stainless-steel stock.

The channels (more on terminology later) have been bent, screwed and glued, and the dashboard has made a decent shelf at the forward end of the cabin. And finally, for this instalment at least, conduit for wiring has been laid beneath the deck, a decision has been taken on the ballast and we’ve measured up the locker under the cabin sole into which the lithium battery needs to go. It’s a good thing lithium batteries can lie on their sides!

No straight edges – How cockpit coaming meets cabin side

The plywood coaming (with a small segment of trim) leaves a V-shaped gap at the cabin edge. Credit: J B-Brown/brownephotographics

The gap is plugged with this triangular piece. Note the matching angular plane across the top

Kim uses a scrap block as a template capping piece to join the trim to the cabin side.

Using the router to gouge out channels in the underside…

…and the plane to shave off enough to butt up smoothly with the cabin side

The template becomes a unique capping piece in matching timber ready for final shaping

Carpentry school

The end of the school term has freed up City & Guilds instructor and team leader Jon Carver to devote a few weeks of uninterrupted time to the project. Alongside him is Jesse Doyle, an IBTC qualified builder, and now also Kim Owen, who works with some of the charity’s most difficult students during term time.

She has training and experience with challenging behaviour but also has work experience as a furniture maker, so the job at Oarsome Chance combining her love of woodwork and experience with young people is a dream come true for her.

Kim was first put to work filling and fairing the hull, using 180 grit ceramic sanding discs on an electric hand sander with a vacuum dust extractor attached. Any voids were filled with a mix of low-density micro balloons and WEST System epoxy spread on with a putty knife and smoothed. Once the next undercoat goes on, the process will be repeated.

Ceramic sanding disc for sanding back the hull

“I’m quite anxious to get the hull painted soon,” said Jon. “Definitely an undercoat and topcoat so we’re not rushing to get that done last minute. There will probably be a final coat before we go.”

Kim’s next project was devising a capping piece for the join between the cockpit coaming and the cabin bulkhead – one of the fun pieces referred to earlier. This involves calculating half a dozen opening and closing angles plus different thicknesses.

Each build would require a different part – no two kit boats will be identical – so it would be impossible for the designer to supply this part. But it’s these curves and the flared sections that make each boat a work of art, so the effort will surely be well worthwhile.

The varnished ‘dashboard’ creates the edge of a shelf once the foredeck stringers are covered by a plywood plank

Dashboards and Channels

The dashboard on a Secret 20 is a curved, varnished bit of trim – supplied mostly finished with the kit – that creates a useful fiddle for the shelf in the cabin by capping the aft end of the foredeck inside the boat. It resembles an old 1950s automobile dashboard, but there are no indicators or dials on it. I certainly think it will be a key feature in the cabin once finished – a decorative piece that will keep bits and bobs: wallets, keys, phones and probably plenty of other bits safe and dry below.

One of the last remaining parts supplied with the kit was two lengths of laminated cedar, described in the instructions as Channels. The terminology was lost on me, so Jon pointed to the 3in thick ‘wings’ attached to the gunwales at the boat’s widest point.

Tom Cunliffe’s book Hand, Reef and Steer is a mine of information about bowsprits and all other subjects surrounding traditional gaff rig. The book is available from tomcunliffe.com

I had an inkling that they were really called Clamps – a term that was also familiar to Jon from his previous experience working on older boats. However, to settle the argument, I contacted gaffer guru and the author of Hand, Reef and Steer – the traditional boatman’s bible – Tom Cunliffe.

Tom explained that a Clamp is basically another word for an inwale on traditional small wooden boats. “It provides longitudinal strength where the ribs and frames stop at the top plank,” he said. But the ‘swellings’ on the sides of the Secret 20 are most certainly Channels. “A channel exists to spread the shroud base. Lots of Victorian yachts, which were quite narrow, had them.”

The chainplates will be bolted to the topsides below the channels and be shaped to angle outwards to the full width of the boat amidships. The forward chainplate is in line with the mast foot according to the plans, while the aft one is between six and eight inches abaft.

Interior plywood backing plates strengthen the hull where the chainplates attach. These were fitted when the boat’s side panels were bent over the frames and stringers back in 2017.

Mast foot and bowsprit heel

The boat’s two key spars are mounted near each other on the deck and must withstand significant compression forces. The mast will sit in a stainless steel tabernacle, which came with the kit. Jon decided to add two extra coachroof stringers either side of a large hardwood reinforcing block to support the mast foot. The mast tabernacle will bolt through a deck-mounted pad, through the tongue-and-groove coachroof pieces and then the interior reinforcing block.

The laminated channels were roughly curved to the hull shape before delivery but needed extra planing and some time spent dry-fitted to take the shape of Harvey’s actual hull shape

The interior plywood backing for the chainplates were fitted back in 2017

The hardwood reinforcing block will be covered by the coachroof and an external block beneath the tabernacle. The two extra stringers are fitted either side

The bowsprit on the Secret 20 is frankly enormous, hence the post into which the heel fits at the inboard end – the Samson post – is a significant chunk of timber.

The Samson post slots through the central foredeck beam which is strengthened by solid timber knees and will be bolted to the bulkhead

The below-deck section is narrow like a keel with a much longer chord length fore and aft.

A corresponding slot is cut in the central fore-aft stringer, which is surrounded by supporting knees.

Below decks the post is bolted through the main bow frame that seals the front end of the cabin.

A mortice joint in the forward face of the post keep the bowsprit secure under sail.

The truth about cutters

Classic boat expert Tom Cunliffe explains the role of the bowsprit on traditional gaff cutters

There’s a lot of nonsense talked about modern Bermudan cutters. I should know. I own one. She isn’t really a cutter at all. She’s a masthead sloop with an inner forestay that sets a staysail if and when I feel like it.

Some such cutters even have a short bowsprit to shove the masthead forestay a little way outboard. If anything happens it’s ‘bye-bye rig,’ so the bowsprit is permanent and supported accordingly.

A true cutter is different, and so is her bowsprit. Here, the main forestay runs from the hounds to the stem head or just inside it. It holds up the mast and carries the staysail. Outboard is a bowsprit, often long and relatively lightly stayed, whose only function is to set jibs.

It doesn’t support the rig unless the boat has an independent topmast, when it may sport a topmast forestay. This means that if the bowsprit is lost, the topmast may go as well, but because this spar also isn’t critical to the integrity of the lower mast, you can shed a tear and wave it off.

A cutter’s bowsprit can be sited to one side of a stemhead, or on the centreline. Either can be withdrawn or steeved up to make the boat shorter in harbour. Which is favoured is anyone’s guess, but a Thames sailing barge hauls her mighty bowsprit up using a spare halyard. The spar simply hinges on the fid that secures the inboard end in place.

Dutchmen have done the same for hundreds of years and the method is so handy that it can be found even on some Falmouth-built cutters far from home.

Down west and on big sailing trawlers all round the coast, the generally favoured system for cheating the harbourmaster out of a few quid is to remove the fid that passes through the spar to hold it out against the compression of the jibs, then slide it inboard along the deck.

It’s untidy, but effective.

Fitting the rudder

The rudder stock is a stainless post welded to a flat panel. The post extends up through the hull, cockpit sole and aft seat with a specially fabricated cap for the top that leaves an easy surface to attach the tiller. A length of orange plastic pipe serves as a bush, or sleeve.

A half-inch stainless tube was supplied with the kit that will be embedded in the bottom of the rudder and accept the male insert fixed to the strap running from the bottom of the keel.

Article continues below…

PBO Project Boat Secret 20 update: Bulkheads and beams

Designed in Australia and built by enthusiasts all over the world, the Secret 20 packs grace and pace into her…

PBO Secret 20 Project Boat update: Spars, partitions and trims

The Secret 20 is a beautifully-shaped wooden sailing yacht designed by Derek Ellard and available to the DIY enthusiast in…

The inner sections of the rudder are a pair of plywood parts with timber cheeks glued on. The top has to be rounded so that it won’t strike the hull when fully turned.

The angle of the hole drilled through the cockpit floor at an earlier stage of construction was such that 5mm needed to be removed from the trailing edge of the keel to keep the rudder from fouling. There is now a consistent gap between the leading edge of the rudder and the keel.

“There might be a fill piece at the leading edge still to make up just to make sure it’s a tight fit, up against the trailing edge of the keel,” said Jon. “I’ll get the pintle sorted, dry fitted and then I’ll take the rudder off and glass it.” The stern cladding will also be rounded off and sheathed at the same time as the rudder.

The rudder stock is a stainless rod welded to a flat panel

The inner sections of the rudder are a pair of plywood parts with timber cheeks glued on. The top has to be rounded so that it won’t strike the hull when fully turned.

Jon offers up the rudder. The trailing edge of the keel needed trimming to match the angle of the post hole through the hull.

A specially fabricated cap for the post will attach to the tiller. Note the orange pipe serving as the sleeve for the post.

A half-inch stainless tube was supplied with the kit…

…to be embedded into the leading edge of the blade

Making sail

Scruffie does not typically offer builders the option to make their own Secret 20 sails, instead there are attractively priced bundles including finished sails, cordage and chandlery all in one. But Oarsome Chance is a resourceful organisation with an existing social enterprise called Canvas Works that was set up by one-time regular volunteer Nick Walters. And Nick has volunteered to make Harvey’s sails using cream-coloured sail cloth donated by Contender Sails.

Nick is a marketing director by profession but makes canvas covers, sprayhoods, boom covers and sail repairs in his spare time. What began as a one-off project to repair some canvas while living aboard cruising the Atlantic coast of Europe and the Caribbean with his family, has taken over his double-wide garage at home in Eastleigh, near Southampton, where he has six sewing machines and a large cutting bench.

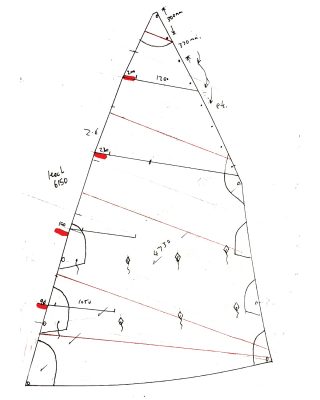

The main sail diagram supplied by Scruffie to aid OC volunteer Nick Walters in making sails

“It’s a hobby gone completely bonkers,” he tells me. Nick now sails a SHE 36 on the South Coast but describes himself as a ‘tweaker’ when sailing – someone who constantly adjusts his sails. “I’m fascinated by these aerofoils and the controls that adjust and shape them,” he says. “I’m hoping to retire from office work in a few years and see if I can make a go of canvas work and sail making.

For the show, he plans to put together a set of mesh sails so there is no chance of the wind blowing the boat over. But work has begun on the real sails too: “We have started working through the plans in detail and making decisions on certain aspects of the build,” Nick told me.

The diagrams supplied by Scruffie are a mix of imperial and metric measurements, so the first step is to turn them into a digital file so that the cloth can be laser cut. Nick has also spoken to North Sails about possibly using one of their large loft facilities (on a weekend) to speed up the job.

The design calls for a canvas main hatch cover. Here the hatch trim is being fitted

Canvas works

There is no solid main hatch cover for the Secret 20, although some builders have improvised. The suggestion is to simply use a canvas cover, which the charity plans to make itself.

Canvas Works (CW) is a social enterprise project within the Oarsome Chance charity. The charity collects and repurposes old and in some cases famous sails into bags and other products. The latest project is making medical equipment bags for people who are undergoing chemotherapy.

The charity has a mezzanine floor above the main boatshed with a cutting table and industrial sewing machine. Find out more on the Oarsome Chance website.

Conduit for cable run is located beneath side deck

Decisions, decisions

At time of writing, a number of key decisions were still up in the air (most of which will have been decided by the time the boat is on display at the show): in particular the colour scheme. Also Jon Carver was keen to include some sort of decorative cladding for the aft panel of the cockpit right behind the tiller. And portlights: how many and what style? Bronze? Chrome?

The underfloor compartment in the cabin has to hold the house battery as well as some of the recommended 50-100kg of ballast, which could be a tight squeeze. The Lifos 68Ah lithium-ion has a smallest dimension of 175mm (lying on its side), so is already going to be an ‘interesting’ fit. Jon prefers movable ballast, such as a collection of sash weights or diving weights in preference to permanent, epoxy encapsulated ballast such as lead shot or gravel.

Cockpit drainage is also a concern: The cockpit sole very quickly captures a large amount of water in the rain and will inevitably collect some spray under sail, so some drainage at the aft end into the outboard well is planned. A bilge pump beneath the cabin sole is also in the offing, but linking the drainage to the outboard well is probably going to be required as well.