Frank Sibly enjoys trailer-sailer coastal hopping from Northumberland’s Seahouses to Scotland’s Dunbar Harbour

Getting our trailer-sailer to the Scottish Borders involved a seven-and-a-half-hour, 350-mile drive from Herefordshire.

My wife, Sue, and I launched my Etap 22i at the lifeboat slip at Seahouses. Sue was planning to enjoy the harbour visits and to join me as crew for the short voyage legs, but to follow by car while I sailed the longer legs solo.

The well-constructed Seahouses slipway is 150m from the lifeboat station, down a narrow public road, along which the lifeboat has to be hauled on a trailer by a tractor.

You therefore need to park carefully when assembling the boat for launch, to avoid obstruction. The slipway slope is quite shallow, so the trailer had to be submerged to launch it.

After launching, we flush the hubs with fresh water. Our new stretchy garden hose was ideal for the job, but the tightening mechanism on our tap-hose connector had rusted up, so we had to hold it on by hand: I must remember to replace them every year!

We then needed somewhere to leave the trailer, something that is becoming increasingly difficult. Eventually, we found a caravan storage business willing to take it for just a week, for which I offered £60, which was probably a bit too much.

Coast-Inn, Frank’s Etap 22i trailer sailer in Eyemouth Harbour, with one reef set, ready for a moderate wind forecast. Photo: Frank Sibly.

Promising forecast

Seahouses, actually known as North Sunderland Harbour, is very busy with passenger boats going out to the Farnes to view the grey seals and seabirds.

A new pontoon was installed in 2025 in the outer harbour (minimum depth 0.3m when we were there on Neaps), which can be made available to visitors for short stays if arranged with the harbour master. The town is interesting, with good shops.

We ate at the Olde Ship Inn, which is full of history and was visited by the King when he was Prince of Wales. The adjacent pub has a wonderful terrace with a panoramic view. There were Eider duck in the harbour, prized in previous times for their feathers for making eiderdowns…

The Windfinder app predicted several days of gentle breezes from the south, backing easterly, so we planned to start the cruise along the Northumberland coast at its southern end.

This slipway is shared by the RNLI Seahouses Lifeboat crew, so be sure to park your trailer sailer well clear. Photo: Frank Sibly.

Along with wind direction and strength, this would get the benefit of the tidal stream, while leaving and entering drying harbours with sufficient depth of water and in daylight.

In this area, the stream changes about mid-tide, ie local high water (HW) is halfway during the south-going flood, local low water (LW) is during the north-going ebb.

This is because the HW tidal wave comes in from the Atlantic at Land’s End, splitting into two branches, one taking six-and-a-half hours to go up the English Channel to Dover (HWD), then Harwich, arriving at HWD +1.

The other branch goes clockwise round the west and north coasts of Britain, reaching Wick at HWD, then continuing down the East Coast to Harwich, where it meets the next HW wave to come up the English Channel.

The most interesting parts of a cruise to me are navigating into new harbours and exploring ashore. I also like the passage to be less than 20 miles, as sailing single-handed for more than six hours is tiring.

Seven mile start

The Old Law beacons off Holy Island provide a helpful navigational fix. Photo: Frank Sibly.

The first leg was seven miles to Lindisfarne, also known as Holy Island. Our route took us close to the Inner Farnes to see the puffins – which are ground-nesting birds from Greenland, only coming to the UK in spring to breed.

We chose the Inner Sound passage as the alternative, Staple Sound, has unmarked rocks with no clear transit. Indeed, the whole of this coast is strewn with rocks.

Out at sea, the North Sea breeze made me feel surprisingly cold on a summer’s day, despite wearing many layers.

Most of the sailing for the first two days was with the wind dead astern. Following a previous scalp wound due to a gybe when running single-handed, I forewent the mainsail, and made good progress under genoa alone.

From the Farnes, the route to Holy Island is difficult to pick out. The green conical Swedman buoy marks the northern end of the Inner Sound, followed by the East Cardinal Ridge buoy, off Lindisfarne, but both are only visible from about 400m.

After the Ridge buoy, it is only a few hundred metres to the Triton buoy, but the route crosses the bar, with turbulent water even in otherwise calm conditions, exacerbated on this occasion by wind over tide.

Taking on a drying harbour in a trailer sailer

Frank’s Etap 22i trailer sailer, with a lifting keel, settles in the Ouze drying harbour. Photo: Frank Sibly.

The transit provided by the tall, slender stone beacons of Old Law then guide you through the first part of the dog-leg channel. However, the beacons are the same height, which caused me some difficulty in finding which way to steer to align them.

This transit is followed until the next one comes into line – the chapel in line with a metal framework beacon, which is about a 90° turn to starboard. The safe channel is only 200m wide.

The stream in and out of the harbour is strong (up to four knots), and can be going westward into the harbour, when the stream outside is going south-easterly. You can therefore have the tide with you going up the coast, only to find it is against you in the harbour approaches.

To avoid the north-easterly end of the Ridge reef, I kept on transit until the end of the harbour pier (known as Steel End) was due north. The pilot guide says you can anchor outside the harbour to stay afloat, but the strong tidal stream and swell make it uncomfortable.

Our 20-foot trailer sailer has a lifting keel, so we put our legs out in the drying Ouse area. Once Coast-Inn settled, we walked ashore on firm mud.

We had three hours before the tide returned. The many wading birds included a sandpiper. The old coastguard lookout provides local information and a wonderful view.

Trailer sailers are for seadog snuggles

Bert, the ship’s dog, in skipper’s berth. Photo: Frank Sibly.

Lindisfarne has about 170 houses (half for the 150 permanent residents, the rest are holiday lets); there is a primary school, post office, two pubs, two hotels, three cafes and a farm, but no GP surgery.

The public toilets have 24-hour opening. The houses are substantial, and the castle was redesigned in 1901 by architect Edwin Lutyens for the founding editor of Country Life, who wanted a holiday retreat. It’s now owned by the National Trust.

The island economy in Victorian times included lime production, and the remains of a horse-drawn tramway are visible near the castle. Tourism came with the opening of the East Coast mainline railway in 1847.

The one-mile causeway, built in 1954, runs from a peninsula called the Snook, and gives access for half of the tide, but there is no passage by boat around this north-western side of the Island. We had a peaceful night, although the ship’s dog found his way onto my bunk.

In the morning we had to wait for enough tide to float, by which time the stream was against us on our way up to Berwick-upon-Tweed, 13 miles away.

Even though the exit from Holy Island is in a southerly direction, we were pushed back by the strong stream flooding into the harbour, and had to use the two rear transits, motoring four miles to Emmanuel Head before we could sail on a course of 300° to our destination.

On the approach to Berwick, we used the transit (lighthouse in line with the town hall spire) to avoid being swept off course by the current.

The entrance over the bar was choppy, despite calm conditions, with the pilot guide advising to keep close to the breakwater. An ebb tide in the river, combined with an onshore wind, can be dangerous here.

At the breakwater ‘knuckle’ there is a red buoy, and a second one has been added because of the shifting sands.

Until I got closer, I could not find the transit on 207° of two orange beacons, so I used a course towards the next marker 300m away. Soon we arrived at the Royal Tweed Dock entrance, so narrow it is hard to work out how the 80m coastal vessel Victress gets in.

Sailing a rocky coastline on our trailer sailer

On the approach to Berwick-upon-Tweed’s harbour entrance, Frank used a transit of the lighthouse and the town hall spire to avoid being swept off course. Photo: Stock87/Alamy.

The name Berwick may derive from ‘barley town’, and barley continues to be imported and exported. Oilseed rape is also exported, and fertiliser is imported.

As elsewhere, the harbour masters were welcoming to our leisure vessel at their commercial port.

Most buildings in the old part of town are substantial and Victorian. Bridge Street on the north bank has smart cafes, and at the Curfew micropub – just a door in the wall leading to a backyard – staff kindly filled our water containers.

Later, the assistant harbour master showed us to the facilities block in a corner of the port, where there was a tap and a very welcome shower. The only yacht in Berwick that night, we were comfortable on the pontoon.

Our third day was to Eyemouth, and I delayed departure as there seemed to be no wind, yet out at sea, there was a Force 4. This 10-mile leg took three hours with the tide, seeing speeds over the ground of seven knots.

I needed to keep half a mile off the rocky coastline, which can be difficult to judge, so I used the Automatic Identification System (AIS) to check.

Nearing Eyemouth Harbour, even with the engine on, a porpoise came to greet us. The entrance is between outlying rocks, and I couldn’t initially spot the small north cardinal marker.

However, there is a good transit in hi-vis orange boards through the narrow 200m channel. Large wind farm offices and stores are adjacent.

The 17m-wide entrance, known locally as The Canyon, has no visibility through it, nor room to manoeuvre once in it, so all vessels must radio the harbour master on Ch12. Out of hours, put out an all-ships call on the same channel to determine if anyone else is about to use it.

This harbour is busy with crew transfer vessels servicing the wind farms in the Firth of Forth. Eyemouth seems popular with German yachts – there were two on our visit – together with a 1961 Saxon-class wooden 35ft yacht, designed by Alan Buchanan and built in Burnham-on-Crouch.

Combined lifeboat and public slipway at Dunbar. Photo: Frank Sibly.

Sister harbours

Our fourth and final day was 18 miles to Dunbar Harbour. The onshore wind brought mist, but visibility looking into the wind appeared good, I felt sure that it would clear, but had the AIS turned on.

In the Dunbar approach, the groups of rocks need to be identified prior to making a passage. The first transit has beacons with green occulting lights, clearly visible in daylight.

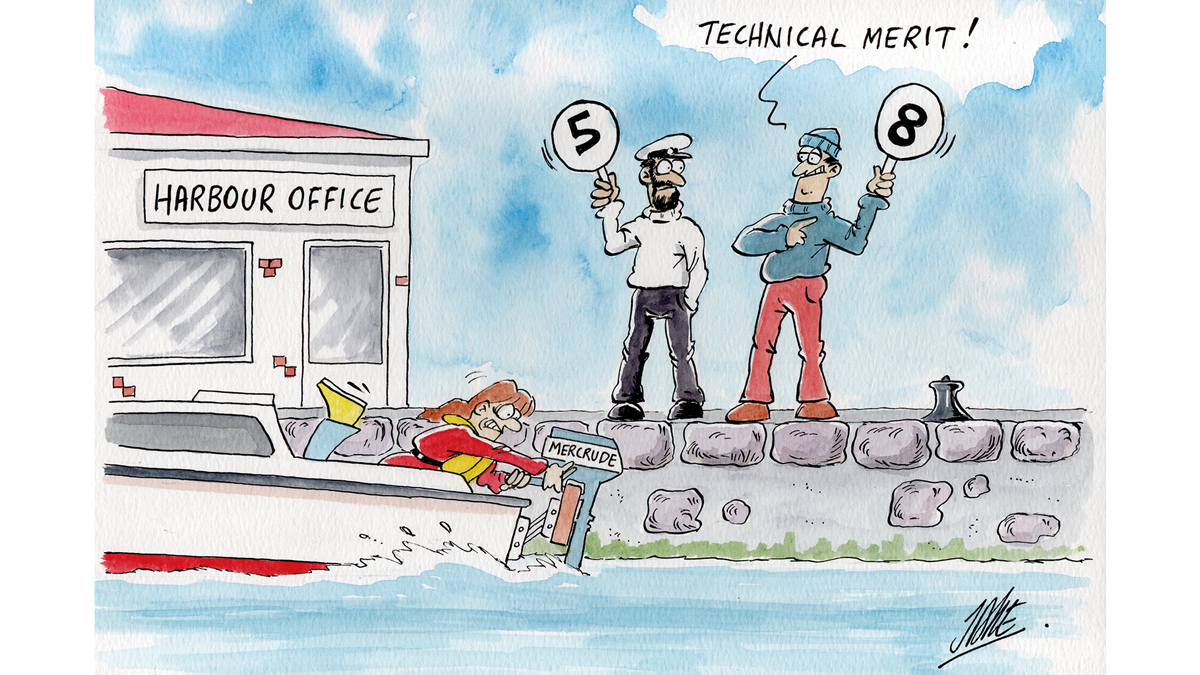

The harbour and its approach are beautiful, and run by Dunbar Harbour Trust which shares its harbour master with North Sunderland.

Access to the inner harbour, where the lifeboat/public slipway is situated, is through a small lifting bridge.

There is a concrete track extension to the slipway, going about 100m, passing out into the outer (Victoria) Harbour, so that even at LW the lifeboat can be floated off its trailer. We retrieved the boat near HW, and were home before midnight.

A trailer-sailer adventure on the Scottish/English borders east coast

The cabin interior shows that most of the berth is under the cockpit. Behind the wooden screen is the sink and cooker. The vertical structure is the lift keel housing. Photo: Frank Sibly.

Our boat: a neat little trailer sailer

For comfortable coastal cruising, look for at least a 20ft length overall (LOA), with the outboard in a cockpit well, protected by a high transom. The maximum width that can be towed in the UK is 2.55m.

A lift-keel boat is necessary to get on and off a trailer. Yacht legs give a bit of protection when drying out; our Etap 22i trailer sailer has factory-fitted attachment points for the legs.

The trailer

Gross weight for a single-axle trailer must not exceed 1.8t (which includes the trailer, outboard, inflatable dinghy, yacht legs etc).

On the road, move heavy items in the boat forward to stop the trailer from snaking. For launching and retrieving, they need to be moved to the stern.

The trailer needs regular attention: greasing the break-back pin, replacing the winch strap every three years or so, changing the wheel bearings every couple of years, replacing the tyres every 10 years, and replacing the bellows covering the brake actuator, if it has a hole.

Flushing out the brake drums with fresh water after each use is important, but it does not protect the bearings.

When travelling, I have readily accessible a jack, a ¾in socket-drive for the road nuts and axle nut, torque wrench, and a spare brake drum with bearing already fitted. The only road rescue I have found that will take this size of trailer is the AA.

Snug accommodation on a trailer sailer

Our 20ft micro yacht/trailer sailer cabin does not offer standing headroom. To get to the forecabin, we have to crawl round the case of the lift-keel.

The two main berths go under the cockpit sole – long enough for the dog to sleep at my feet, and most of the food to be beyond the Mate’s feet.

We use the double berth in the forepeak to stow clothes, charts, yacht-legs, folding bikes. We have tried various cockpit tents, but none worked well, so we managed without.

We try to overnight in a port with good facilities, and we enjoy meals cooked on our twin burner meths stove. We occasionally seek refuge in a bed and breakfast. Trailer sailers have many virtues, but space isn’t one!

Weather

I use Windfinder app and BBC and Met Office weather forecasts.

Launching a trailer sailer and harbours

Substantial slipways, suitable for a trailer-sailer, may be 50 miles or more apart. An alternative is to pre-arrange for the boat to be craned in (for about £180) at a boatyard or marina.

I look for harbours 20 miles apart. I average three knots, so even a leg of five miles is pleasant. A consideration with drying harbours is to be able to get out at first light, with enough rise of tide to reach your destination harbour in daylight.

Seahouses notes

- Lots of tripper boats

- The whole harbour dries out

- Inner harbour pontoon is available via North Sunderland harbour master

- Option to anchor in the outer harbour

Holy Island notes

- Drying area on mud inside harbour

- You can stay afloat outside the harbour, but tidal stream is strong

- Idyllic place for exploring

- Tricky navigation for last two miles

- Holy Island, by LJ Ross, a detective story gives insight into island life.

Berwick-upon-Tweed notes

- England’s most northerly harbour

- Occasional use by large vessels

- Very helpful harbour master

- Good facilities

- Pontoon mooring doesn’t dry out

Eyemouth notes

- Alongside pontoon that doesn’t dry

- Beware the narrow steep-sided entrance, with limited visibility: radio the HM for permission to enter/exit

- Busy with the wind farm boats

Dunbar notes

- Beautiful harbour with ruined castle

- Prominent rocks require careful navigation but green lights assist

- Visitors berth to immediate right after entrance

Navigational aids

Admiralty Small Craft Chart 5615 Whitby to Edinburgh

2: Blyth to Berwick-upon-Tweed

3: Saint Abb’s Head to Buddon Ness

7: Amble to Farne Islands

8A: Holy Island to Saint Abb’s Head

9: Saint Abb’s Head to Fife Ness

22A: Farne islands to Holy Island

Pilot guides:

East Coast of Scotland, Sailing Directions, Andy Carnduff, Forth Yacht Clubs Association, Imray

Cooks Country, Spurn Head to St Abbs, Henry Irving, Imray

Frank Sibly is retired, enjoying running a small arable farm, and has been trailer-sailing for 24 years. He aims to do three sail cruises each year, when the weather is fair and the days are long. The first mate and ship’s dog often prefer to travel by bus, rather than boat, between the harbours. Frank is always happy to hear from those interested in trailer sailers.

How to get started with a trailer-sailer: Everything you need to know

Ever considered getting a trailer-sailer? Some think they might just be for pottering around harbours, but they couldn’t be more…

The best trailer sailer boats for weekend cruising… or longer

Duncan Kent reviews a selection of new and used trailer sailer boats that are large enough to accommodate crew for…

How to launch a trailer sailer (and the key mistakes to avoid)

George was helping to launch his friend’s boat and asked if Paul and I could give them a hand. My…

The new BayCruiser 21: Is this the best trailer-sailer ever built?

17 years after kick-starting a revolution in trailer-sailing, Swallow Yachts has launched the BayCruiser 21. The new model is light,…

Want to read more articles on trailer sailers?

A subscription to Practical Boat Owner magazine costs around 40% less than the cover price.

Print and digital editions are available through Magazines Direct – where you can also find the latest deals.

PBO is packed with information to help you get the most from boat ownership – whether sail or power.

-

-

-

- Take your DIY skills to the next level with trusted advice on boat maintenance and repairs

- Impartial, in-depth gear reviews

- Practical cruising tips for making the most of your time afloat

-

-

Follow us on Facebook, Instagram, TikTok and Twitter