Ben Meakins and the PBO team examine the techniques of towing and being towed astern at sea, trying out the textbook theories in practice

We’ve all seen the textbooks with their diagrams showing boat towing at sea, but few of us have put the theory into practice. There’s no doubt it’s a useful skill to have, so to find out what we should do in a towing situation we headed out with two boats, my Impala 28 Polly and a Westerly Fulmar, Hakuna Matata. We wanted to learn what works – as well as finding out what doesn’t – and to prepare ourselves and our equipment in case we ever needed to tow or be towed in earnest.

When boat towing at sea, the only safe way to tow another boat is by towing astern – it keeps the boat safely astern, out of harm’s way, with minimal danger. It’s a different story when it comes to towing in the confines of a river, when you’d be better off with an alongside tow.

Boat towing at sea: Accepting a tow

Whether you’ve had engine failure or lost steering, the first thing to do is to make sure you’re not in immediate danger – ie drifting into a shipping lane or running aground. If necessary, and it’s safe, consider anchoring to maintain position and get things sorted out. Our small, light boats drifted surprisingly fast downwind under bare poles while we were setting up. If you have enough crew, it’s worth detailing one of them to maintain a good watch while you get ready for a tow.

Call the coastguard on the VHF radio to keep them informed of your predicament. While sorting out ropes and negotiating a tow, it’s easy to lose sight of the bigger picture – such as the large ship which glided by as we were setting up our tow.

Boat towing at sea: Choosing a tow rope

The basic rule with a tow astern is ‘the longer the rope, the better.’ When towing in waves, the rule is to allow a wave length between the boats so that each boat rides the waves with the same rhythm, reducing the strain on the tow rope. It doesn’t matter whose ropes you use – just pick whichever is more suitable. In an ideal world, you’d use long mooring lines to rig your bridle, and a long, stretchy anchor rode as the tow line. Choose the thickest, stretchiest ropes you have on board – plaited and three-strand ropes are generally preferable to braided lines.

Rigging a bridle: the tow boat

Towing another boat, or being towed, is likely to put an unusual strain on your boat’s fittings, and snatch loads can overwhelm a single mooring cleat. Liquid Vortex, the Bénéteau 40.7 that was rescued off Dover in a Force 10 in 2011, saw her bow cleats ripped out in a big sea by the lifeboat’s towing line.

The textbooks recommend that yachts both being towed and doing the towing set up a bridle to spread the load over a number of fittings. On Hakuna Matata, we rigged a bridle starting from the midships cleats, passing around her primary winches and, finally, through her aft mooring cleats. We attached the towing line to the bridle using a bowline with its loop free to run on the bridle. This slides from side to side to centralise the pull, avoiding the tendency of the towed boat to pull the towing vessel’s stern around. The longer you make the bridle, the more it can stretch to absorb any snatch loads on it.

We had to join two lines to make our bridle, but made sure one side could slip so that we could release the tow under load.

What we learned: It’s a good idea to practise rigging a bridle, and remember which of your lines goes best where: write it in the log if necessary. A single turn, rather than a figure-of-eight, around each intermediate attachment point allows the rope to surge without overloading any one fitting.

…and finally led through the centre of the mooring cleat on each side. A single round turn would have been better to spread the load more evenly.

Rigging a bridle: the towed boat

As with the towing boat, you’ll need to make a towing bridle. On Polly, we didn’t have a long enough line to make a continuous bridle, so we rigged separate lines from the stern cleats, leading them forwards with a turn each around the small cockpit sheet winches, inside the shrouds and with a turn around the bow cleats. We then tied a bowline using both lines to make an attachment point for the tow line. The bridle lines were led through the anchor roller and held in place with a drop-nose pin. This worked well, but letting the line go in a heavy sea would have been difficult. The textbook continuous bridle is preferable. We could also have joined the lines on deck, leaving one side free to slip.

What we learned: Having a fixed loop attached to the tow line made the bridle hard to slip. A single long bridle line would be much better, as you could slip it by releasing one end from a stern cleat. In general, bowlines are good knots to use when towing because, although you can’t release them under load, they can still be undone even after being under extreme tension.

To rig the towing bridle, we tied off the warp on the stern cleat before taking a turn around the cockpit winches, leading the line forwards and inside the shrouds directly forwards…

…to take a turn around the bow cleats. From here, the lines on both sides went forward to attach to the towline.

Setting up the tow

We were on the water in 15 knots of breeze in a relatively flat sea state, but still, manoeuvring alongside felt fraught with danger – especially from clashing rigs as the boats rolled. This proved to be the most dangerous part of the operation, and the helmsman of the tow boat needs to be aware of the disabled yacht’s leeway, and be ready to clear out if a collision looks likely.

In calm conditions you can simply hand over the tow rope, but in anything approaching a swell you’ll need to be a bit more cautious. We found that transferring a towline worked best if the boat doing the towing approached to leeward of the disabled boat. A traditional two-coil throw (pictured) worked well to transfer the line, especially when throwing downwind. But if the towline is too heavy, or if you are in big seas, it’s worth using a lighter, dedicated throwing line.

On Polly we have a light floating line with a monkey’s fist in one end, which we also tried using as a messenger, naval-style. The heavier towline was tied to the end of the messenger, and Julian, standing on the deck of Hakuna Matata, could haul both across with ease, taking care to keep the lines out of the water and away from the Fulmar’s propeller. Once Julian had the line, David at the helm motored gently ahead, stopping when the boats were no longer overlapped. This gives the two crews time to sort themselves out, and removes any danger of collision. Once the lines are sorted, the tow can begin at a safe speed.

What we learned: A long throwing line will let you keep the boats far enough apart in rough weather to avoid clashing masts or colliding. Add fenders on both boats in case of contact.

Starting the tow

When both boats are ready, the skipper of the disabled boat can signal to the tow boat that he is ready to move on. With a crewman on each boat attending to the lines, the tow boat motors gently ahead, taking up the slack in the line. The aim is to do this slowly enough that the line doesn’t come under immediate tension. Instead, whichever boat has the slack should surge it out so that the tension comes on gently, with no snatching.

The helmsman of the towed boat should be careful to head for the tow boat’s transom, especially when the load is coming on, to minimise snatch loads. When under way, keep the speed down. Two to three knots is ideal: it won’t overload your engine, damage fittings or impose big snatch loads on the rope. Be aware that you are now much longer, and that the boat behind yours may get swept onto buoys and obstructions unless you give these a wider berth than normal.

What we learned: Keep hands clear of ropes and cleats, and flake ropes if they have lots of slack to avoid them snagging round something. Start off slowly

Who is in charge when boat towing at sea?

Being towed was an interesting experience that left me, on the towed boat, feeling a little vulnerable. It’s important that the skipper of the boat being towed is in overall command. If you feel you’re being towed too fast, say so.

It’s best to simply treat the other boat as your motive power. You hear stories of boats suffering damage from being towed at too great a speed – agree in advance a VHF channel for communication, and stay in constant contact. If it all gets too much, stand by to slip the towline.

Weights and catenary

We found that the towline was long and heavy enough in flat water not to snatch, but instead drape in the water – even in the wash from a ferry. At sea, however, it’s a different matter. The key is to add some dampening to the tow rope. All manner of weights have been suggested, but it makes sense to use something almost designed for the job – a length of chain or an anchor.

A lead anchor weight being lowered back along the towline. A length of chain shackled between two tow ropes would be easier to handle when boat towing at sea

We used Polly’s lead anchor weight, which we lowered back along to the middle of the line from the tow boat. Ideally the weight will stay underwater, absorbing the shocks and making the tow much safer. A length of chain, attached in the centre of the towline, is another popular idea. If you have a rope-chain anchor rode you can use this, tied to another line with the length of chain in the middle. In a following sea, the boat being towed may require a small drogue to keep her from overtaking the yacht in front. If she has lost her rudder, then a drogue is essential

Slipping a tow

Slipping the tow is easy in a controlled manner, when you’re ready to glide into your berth or hand over to the harbour master’s launch – you simply slow down and slip the line. But if things go wrong under way, you need to be ready to slip the line under tension. The bridle is an ideal rope to slip as it is usually continuous and can be released under load, unlike a bowline. In the photos below the crew on the tow boat is slipping the towing bridle – but the principle is exactly the same if you need to slip the bridle on the towed boat, too. Flake the end of the rope you’re going to slip to ensure it can run freely. When you do slip it, keep one side cleated and release the other, letting go entirely. If all else fails, or you don’t think you can slip the towline, have a knife ready – but make sure it’s sharp enough for the job, and beware of the rope whipping back under recoil

Boat towing at sea and the COLREGS

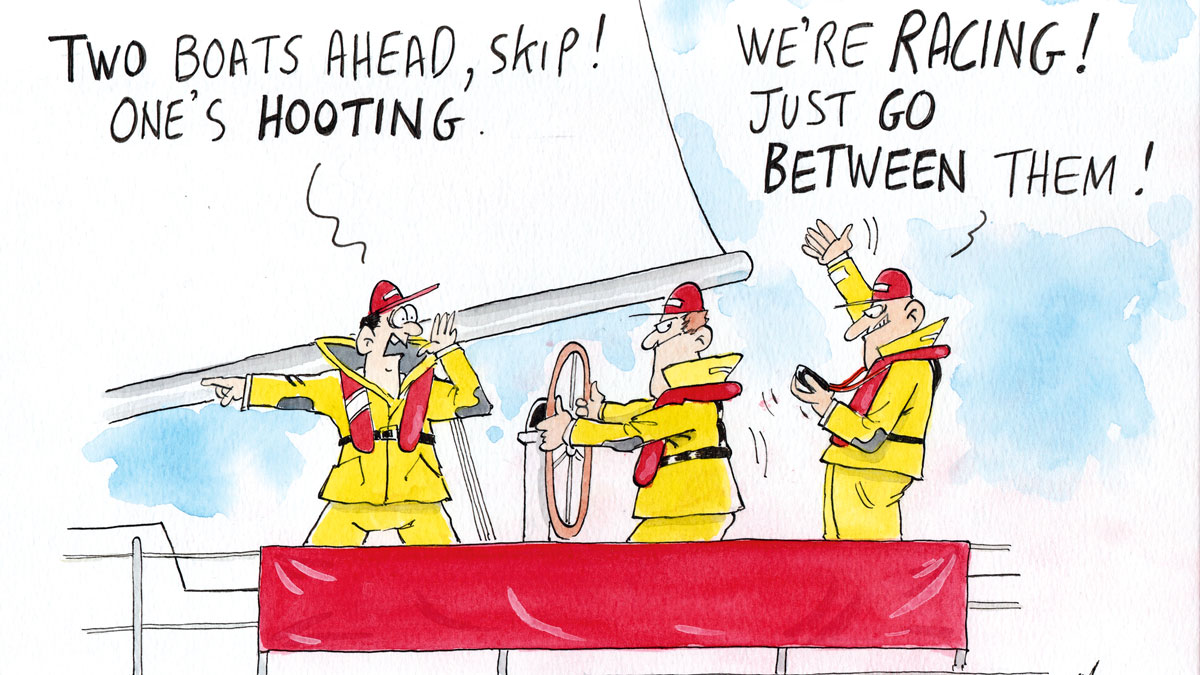

The Collision Regulations specify the lights required for towing with a length of tow under 200m (an additional steaming light and yellow stern light on the towing vessel) – but for most yachts towing another yacht, this won’t be practical. The rules go on to say that if a vessel not ordinarily engaged in towing, is towing another vessel in distress or need of assistance then ‘all possible measures shall be taken to light the vessel being towed or at least to indicate the presence of such vessel.’ A powerful torch, used to illuminate your tow in addition to your standard navigation lights, should suffice. Vessels and their tows are not regarded as restricted in their ability to manoeuvre unless the operation severely restricts their ability to deviate from their course. This means that tows in most circumstances must comply with the Collision Regulations as if they were an ordinary vessel. Sound signals in fog for vessels under tow are the same as for those under sail, fishing, constrained by draught, and not under command – ie one long followed by two short blasts every two minutes.

If someone asks you for a tow

Don’t endanger your boat. If you think your boat or engine are not up to the job, say so – but if you can’t help, it’s courteous to hang around until another tow has been found. If you can help, discuss with the skipper of the disabled boat where and how far you are willing to tow him, and make him aware of your boat’s capabilities.

Salvage claims

We’ve all heard the stories of unscrupulous skippers claiming a hefty salvage bill on a boat they towed home. But accepting a tow does not automatically grant a salvage fee to the towing vessel if you come to an agreement in advance – if you come to an arrangement, that skipper, the salvor, will not have a further claim. Therefore, it’s well worth talking with the skipper of any potential tow boat to ascertain their intentions before you accept a tow. That’s why anchoring or making sure you’re not in immediate danger before accepting a tow puts you in a stronger bargaining position. If in doubt, make your agreement in front of witnesses – your crew – and get them to sign the logbook. If worried, try to use your own lines and minimize the other boat’s involvement. Better still, contact the coastguard initially and let him co-ordinate the tow, making your concerns clear. If you’re towed by a lifeboat, there is no problem – the RNLI will never charge salvage.

Boat towing at sea checklist

Phase 1: Preparation & Safety

- Assess Danger: Ensure you are not drifting into shipping lanes or toward a lee shore.

- Anchor if Necessary: Use an anchor to maintain position while rigging the tow if it is safe to do so.

- Maintain Watch: Assign a dedicated crew member to keep a lookout for other vessels.

- VHF Contact: Notify the Coastguard of your situation and agree on a working channel with the towing vessel.

- Communication: Establish who is in command (usually the skipper of the towed boat) and agree on a maximum towing speed.

Phase 2: Rigging the Bridle

- Spread the Load: Never tow from a single cleat. Use a bridle to spread tension across multiple points (cleats, winches, and the mast if necessary).

- Tow Boat Setup: Run lines from midships cleats, around primary winches, and through aft mooring cleats.

- Towed Boat Setup: Run lines from stern cleats, around cockpit winches, and through bow fairleads/rollers.

- Check Knots: Use bowlines for attachment points. They remain secure but can be undone even after extreme tension.

- Ready to Slip: Ensure at least one end of the bridle is “slip-able” (not tied off permanently) so the tow can be released under load.

Phase 3: The Connection

- Choose the Line: Use the thickest, stretchiest rope available (e.g., a long anchor rode or heavy mooring lines).

- The Approach: The towing boat should approach from the leeward side of the disabled vessel to avoid drifting onto it.

- Transfer the Line: Use a light throwing line (messenger) to transfer the heavy towline between boats.

- Protect the Gear: Use fenders on both boats in case of accidental contact during the line transfer.

Phase 4: Under Way

- Take Up Slack: The tow boat must move ahead very slowly until the line is taut to avoid “snatch” loads.

- Check the Rhythm: Adjust the length of the towline so both boats are on the same part of the wave cycle (one wave length apart).

- Add Weight (Catenary): In rougher seas, hang a weight (like a small anchor or length of chain) in the middle of the towline to absorb shocks.

- Monitor Speed: Maintain a slow, steady speed (typically 2–3 knots) to prevent damage to deck fittings.

- Watch for Obstructions: Remember that the total “length” of your vessel is now significantly increased; give buoys and obstacles a wide berth.

Boat towing and berthing by tender

If your engine fails to start, being able to berth your boat using the tender is an extremely useful skill,…

‘Towing the Drascombe, a racing fleet appeared and like a swarm of locusts gathered around us’

Following a white knuckle marina rescue of three boats during Storm Eunice, Gilbert Park experiences two fairer weather towing adventures

Boat towing: lessons learned from assisting a dismasted yacht in the Atlantic

Ali Wood meets the ARC+ crew who battled squalls and rough seas to tow a dismasted yacht to safety

Towing under sail for 232 miles: Impressive seamanship in the Jester Azores Challenge

"Some 400 miles from the finishing line, the Varne Folkboat Minke lost her rudder" – John Apps reports on impressive feats…

Want to read more articles like Boat towing at sea: how to tow astern?

A subscription to Practical Boat Owner magazine costs around 40% less than the cover price.

Print and digital editions are available through Magazines Direct – where you can also find the latest deals.

PBO is packed with information to help you get the most from boat ownership – whether sail or power.

-

-

-

- Take your DIY skills to the next level with trusted advice on boat maintenance and repairs

- Impartial, in-depth gear reviews

- Practical cruising tips for making the most of your time afloat

-

-

Follow us on Facebook, Instagram, TikTok and Twitter