Triple amputee Craig Wood sailed into the history books with a non-stop, 90-day, 7,506-mile unassisted voyage. Here's what he learned.

Before I set off on my solo sailing challenge, my wife suggested I take yeast. I remember saying, ‘Am I really gonna make bread when I’m out at the sea and it’s 40ft waves?’. writes Craig Wood

But man, was she right. Bread is great out at sea.

I turned 34 during this passage, on 25 April. I don’t eat cake, but I did make bread that day. I don’t know if it was because it was my birthday, but I was definitely craving a burger.

I was thinking, ‘but I’ve got no bread’, and was at the point of having the burgers on their own when I found flour. I had brought just one packet of yeast, which was a terrible mistake. I should have bought lots more.

That day, I made bread and had a big, fat boy burger. I also made a pizza with the spare dough, and later a pretty good chicken pie.

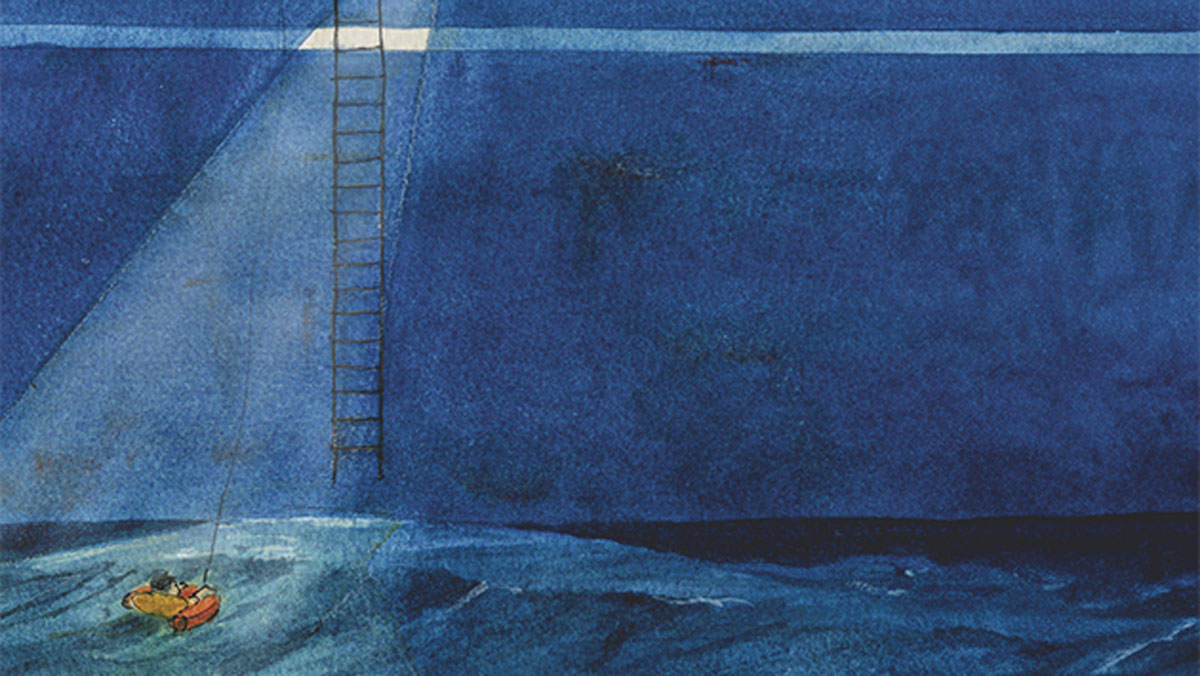

Craig Wood spent 90 days alone at sea, facing down every challenge the Pacific could throw at him, but managed to enjoy himself along the way. Photo: GD Media.

The Pacific challenge: expectations vs reality

When I set off from Puerto Vallarta in Mexico on 25 March, bound for Hiroshima, Japan, my biggest concern was a collision at sea.

Yet during the 90-day crossing, I didn’t see whales or container-sized debris, just your normal trash in the ocean and something the size of a motorbike in a wooden box.

This voyage tested me and my 41ft Galileo catamaran almost to the limit, but I tried to stay in the moment and focus on my goal.

The thought of seeing my wife and children at the end spurred me on. We live aboard Sirius II for much of the year, and I know this boat inside out.

When he is not solo navigating, Craig Wood and his family live aboard Sirius II. Photo: Craig Wood.

I’d also imagined that the ocean crossing was going to be so rough that going forward would be mega dangerous, but this was not the case.

The first weekend had light winds. As soon as I got into the trades, the maximum I saw was 25 knots, the highest reef I got to was second reef, and that was mostly for comfort.

The biggest problem turned out to be hitting the doldrums. I had a week of drifting, and at times even gained miles backwards.

It’s shocking for morale and for the kit when the sails are just slapping around, and there’s no wind, but waves. I worried the battens were going to snap.

In the end, I took the sails down and embraced the drifting.

Rigging concerns

Before I set off, I had fixed my reefing lines to a single line, but the way that my boom is angled created a chafe point at the gooseneck.

Every second week, I was wondering, ‘why are my reefing lines snapping?’

Eventually, I figured it out, and I had to completely re-rig my whole reefing lines, mousing lines and everything while on passage, snap-shackled at the mast that just clips on a D-ring at boom level, take off the sail, and then do a single line at the back of the leech.

Craig Wood had to re-rig all of his reefing lines on the 41ft Galileo catamaran mid-ocean to prevent chafe. Photo: GD Media.

Getting creative onboard

I broke my hook around day 60.

The technique I usually use for pulling in lines is to grab the rope, hook it over, and then double it up so I’ve got double the purchase. It’s like using two hands.

When the mount came off my prosthetic arm, I’d naturally try to use my hook, and find I couldn’t.

Instead, I had to hold the line under my arm, which did inconvenience me quite massively.

Losing the hook also meant I didn’t get a chance to play my ukulele, which I was a bit gutted about. Oh man, I needed an outlet.

Instead, I redesigned the interior of my boat. I made a new door frame for the bathroom door, I re-plumbed the shower; I just started doing jobs and had a really good time.

I also made my own AIS antenna. I got some five-strand, 6mm squared copper wire, cut it at 44.5cm long, two lengths, connected it with a terminal block, one up, one down, and connected the shield to the down one and the insulated core to the top one.

I got a 12-mile range on that. I was very happy.

Spot Craig Wood’s self-made antenna in the background, which he made during his solo Pacific crossing. Photo: Craig Wood.

I did a lot of other fixes at sea, too.

The boom came off – the pin that secures the boom into the gooseneck slid out in the middle of the night, so to avoid the boom swinging at me in the dark, I tied it forwards to the mast and out to the shroud and dropped the sail, to deal with in the morning sunlight. Then it took me about an hour and a half to fix.

I knew what to do as the same thing had happened on my Beneteau.

I put the boom out to one side, tied it to the shroud, and then got the halyard around the gooseneck and lifted it, and put the pin back in. Then I drilled two new holes and re-tapped and made it all better, drilled a hole in the middle of the pin, and put a split pin in there.

It shouldn’t go anywhere anymore, but I’m still going to get it replaced as I don’t know if I weakened the pin by drilling it.

Dealing with gear issues

Craig Wood at the helm of Sirius II

during his voyage. Photo: Craig Wood.

My two-year-old B&G anemometer broke, and my chartplotter got a black spot of death in the middle of it, right where my boat would be, which was annoying.

Also, my starboard engine hydro-locked, so it will need to be lifted out and replaced.

I was sailing the whole time, but I was checking on it and saw water dripping out of the air intake, and I thought, ‘That’s not good, maybe I should start my engine’. Then I worried I’d break a connecting rod.

I took the injectors off and turned it over. Water was spurting out of every single thing. By the second day, it completely rusted shut.

So I destroyed my engine, and it turned out to be because – some readers will laugh at me for not knowing it – my exhaust went almost directly to the muffler.

This meant that any wave coming in just filled it up and backed into the engine.

I should have had a high loop in the exhaust hose. My port engine’s got it, so I don’t know why this one didn’t. It’ll be a costly problem to sort.

Gennaker woes

With hindsight, I would practise flying my new gennaker before setting off on a 7,000-mile passage, because it ended up going under my boat three times.

The issue turned out to be the snap shackle on the bottom of the furler drum, with a burr on it – a really sharp edge.

When I put all the tension on and the wind’s blowing in, it chafed my tack line, which eventually snapped. So the gennaker was flying up in the air.

I tried to round into the wind to get it to drop onto the boat, and then drop the halyard, but the anti-torsion line went under the boat, so I had to take the line off, and then when I put the sail back up, I had a knot in the very top of the head, so I couldn’t furl it away.

I tried to do the same thing again, but the wind got it and took it straight under my starboard hull. It took me ages to get it out.

Eventually, I plucked up the courage to use it again, and the exact same thing happened.

I’m really good at flying it now, and the worst thing that can happen is it goes under the boat.

In that case, it is engine in reverse to get it from under the hull. As it comes up and under, you’re coming up on the halyard, with the weight of the water once it is above the deck, the wind puts it straight onto the boat.

Life onboard: sleep and skirting traffic

Greetings from a well-wisher at the finish in Hiroshima. Photo: GD Media.

I tethered on whenever I went on the foredeck. There is one video of me not doing it, but the boat’s going 0.2 knots, so I felt I’d be okay if I fell in.

Not that I would choose to go in! I see no benefit in leaving the thing that’s keeping me alive.

Mid-ocean, sleep wasn’t really an issue because there’s nothing there.

My sleep pattern was that I’d go to bed at eight o’clock at night, wake up at 10, then 12 or 2, look around everywhere, set my radar to a 10-mile guard zone, with a seven-mile depth.

And then I’d set my AIS to a 10-mile guard zone again, closest point of approach (CPA) and then time to closest point of approach (TCPA) at 30 minutes. So I had plenty of time if ships were around.

In daylight, it’s hard to see a ship more than six miles away on the horizon. When it’s dark, it’s easy because the ship lights are super bright.

Arriving in Hiroshima ahead of schedule

The final four days, coming into Hiroshima, I arrived too early.

I’d told the Japanese coast guard to expect me on Tuesday, 24 June at 3pm, but I arrived on Sunday, 22 June, and the earliest they could change it to, was Tuesday at 10am.

I should have waited out in the deep water with fewer ships to get more sleep. The authorities are strict, there’s not much wiggle room. If I’d planned better, I could’ve alerted the authorities in a more timely manner.

As it was, I was just drifting around, staying awake, 30 minutes on, 30 minutes off.

It was very difficult because the domestic fishing boats don’t need to run AIS, so you don’t really have a warning from them; you just hear a huge engine.

On the last day, I woke to see two fishing boats circling me. They must have thought the boat was drifting or there was an issue. When I went on deck and saw thirty boats around me, I knew it was time to go.

I slowly made my way to Hiroshima.

Craig Wood looks back on his Pacific crossing

Overall, the Pacific crossing was the most enjoyable sail I’ve ever had. Frustrating at times, difficult at times, but just everything I wanted it to be, and a little bit more.

I’m fully satisfied with achieving this solo Pacific Ocean crossing, but I don’t want to do this sort of thing again because I miss my family too much when I’m away from them. Most of the time I just wanted to show them the things I was learning on this trip.

I learned a lot from being isolated for so long. Namely, to count your blessings.

My wife and I welcomed another son on 8 October. We now have three under five.

My two older kids, Amaru, aged four and Madeira, three, are too small to understand what it’s been about. All they really know is ‘daddy’s not there, he’s sailing’, which is kind of sad.

But they missed me terribly, and I missed them terribly. My real goal now is to be a present father and husband.

Craig Wood is greeted by his parents at the finish of his Pacific Ocean voyage. Photo: GD Media.

Being back on land has also taught me how skilled and comfortable I really am on a boat. On land, I feel like a fish out of water. The daily tasks of maintaining the boat are more enjoyable than the daily home tasks.

I feel very fortunate to have found my thing in life and will keep going as far and for as long as it’s good for the family. I also love mentoring new sailors and have really found a calling for it.

Overall, I’m just happy; I get to motivate people, change perceptions of possibilities and feel connected to the thousands of sailors that have come before me and that will no doubt come after me.

Craig Wood’s essential kit for an ocean crossing

AIS and radar were my best kit on board for sure.

With radar, it’s important to learn what the interferences are and how to make the gains. Don’t keep it in auto, or it may not pick stuff up.

At first, I doubted the CPA’s precision, but after a while, I realised it’s pretty much bang on. I really started to believe in the kit. I’m not saying it’s the be-all and end-all, but its precision is pretty good.

The autopilot system was my best friend, because that’s how you can sleep as a solo sailor.

At one point, my autopilot kept disengaging. Where the rudder feedback connects to the quadrant kept popping off, and it kept beeping at me.

So I rooted through all of my equipment, found a little L-bracket antenna mount with three holes in it, and the mouth for the rudder feedback arm fitted perfectly on the bottom third hole. My hoarding had finally paid off!

I taped, tied and glued that on there. I’m going to pot-rivet it on because that’s a really good fit, and it has worked fine ever since. I’m really happy with it.

I wasn’t an initial convert to Starlink, but it’s way quicker than IridiumGO! I used it for weather reports. I tried downloading them on IridiumGO! but 40 minutes later, I still didn’t have one, then I turned on Starlink, and it took seconds.

Craig Wood celebrates on the dock at the finish line in Hiroshima. Photo: GD Media.

Satellite communication enabled me to share updates on social media, it makes connectivity so easy. A daily log is good to do just to have something to look back on.

I also used Chat AI to problem-solve my engine trouble and to find out how to do the antenna. It gave me fixes at sea, I followed it, and it worked.

I had paper charts on board and used my sextant because I wanted to check that I actually understand this skill set.

I’m truly amazed by the maths that went into it. I like to learn it and utilise the calculations. It’s a great backup to have, but it’s so much easier to use a chartplotter and a secondary chartplotter.

I’ve got a bit of an irk that my two-year-old B&G system shouldn’t be breaking, and my brand new spinnaker drum shouldn’t be snapping, but it did.

Other much-used gear included a watermaker, Crewsaver lifejacket, SOLAS-approved clip-on LED flare, a SmartFind personal locator beacon and personal AIS.

Above all, know your boat and how to fix it. Crossing the Atlantic or the Pacific is much easier when you know every system on board and have sailed your boat a fair distance first.

The end of an ocean voyage

Reaching Japan, I was exhausted but so proud to complete an expedition that many thought impossible.

But it has been about more than just miles at sea – together we’ve raised more than £65,000 so far for Blesma limbless veterans charity and Turn 2 Starboard, the forces sailing charity.

Every pound goes toward giving others the same hope and support that helped me rebuild my own life after injury. Huge thanks to everyone who donated. You’re part of this journey too.

Craig Wood with his wife, Renate, and eldest son, Amaru and daughter, Madeira. Photo: Renate Wood.

The welcome home was amazing. There was a torrential downpour that day.

My mom and dad flew out a week before I arrived and came out on a boat to greet me, and my wife and children were waiting for me ashore.

I also had so many kind messages on social media, which has been overwhelming but good.

Craig Wood’s top lessons from his pacific crossing

- Get your systems right. Top gear for me was a really good autopilot system, as that’s how you can sleep; a great radar, but learn how to use it – learn what the interferences are and how to do the gains – and AIS, it’s a really good safety system.

- Check your antennas. There’s no point having a radio if your antennas don’t work, trust me.

- Beware of chafing. Chafing was the continuous battle while offshore, so always carry enough spare line.

- Test new kit before going on a 7,000-mile passage. The first time I’d flown my gennaker was on the trip, I should have learned how to fly that correctly before setting off, so the issue that arose could have been solved sooner.

- Take lots of yeast and flour. Bread tastes great out at sea.

- Enjoy the little things. a coffee, a bird chirping, the sound of laughter. I grew a tomato plant while on passage. I really enjoyed looking after something that was completely non-sailing related. It was a complete separation, and it gave me tiny tomatoes.

- Let the grudges go. There are more important things, like sailing, to focus on.

- Surround yourself with supportive people while you chase and follow your dreams. There aren’t enough people who actually get to reach their dreams, and it’s a really beautiful thing.

- Records are great, but impact lasts longer. This voyage is still raising money to support other amputees across the world, with funds donated to Blesma and Turn 2 Starboard, two of the charities that helped me the most when times were difficult: blesma.org, turntostarboard.co.uk.

Pip Hare’s expert comment

Round-the-world yachtswoman Pip Hare, of Pip Hare Ocean Racing, comments:

Photo: Jean-Louis Carli / IMOCA.

There are many good takeaways from Craig’s record-breaking passage, and so much of what he recounts reminds me of my own first solo ocean crossing and still stands strong in my racing today.

How well Craig dealt with the myriad problems that came his way is a clear demonstration of the level of preparation that went into this solo Pacific crossing.

Craig’s solo crossing didn’t start when he left Puerto Vallarta. When you read about a feat such as this, it’s important to remember all of the hours of preparation and training that went in before the voyage, and that undoubtedly made it the success it was.

Craig learned his sailing skills and gained experience over years, and was clearly able to adapt his sailing techniques to match his own physical abilities, and then when he lost his hook, he was able to adapt his techniques again.

I can only assume this was down to a clear understanding of the mechanics of any one task or manoeuvre and a strong familiarity with how his boat performs, which is so important to success on these long voyages, whether alone or not.

When learning with or without crew, it helps to break manoeuvres down into constituent parts and understand why actions are carried out in a certain order – this also helps avert disaster when things go wrong. Like reversing off his gennaker to empty it of water so he could hoist it on to the deck.

Craig had also spent a lot of time on his boat prior to the crossing, which meant he was able to quickly identify and solve problems, knowing the boat inside out and having seen a lot before.

Technology is important when it comes to collision avoidance, and radar can also help with warnings of squalls. It’s important to set up alarms even if you’re not alone – anyone can doze off on watch.

Don’t forget to adjust the ranges according to conditions. Don’t set and forget.

It’s also a great reminder that making landfall and the associated increase in traffic can be the most risky part of an ocean crossing. You’re tired and used to having the ocean to yourself.

Craig Wood, a father-of-three from Doncaster, set two Guinness World Records in June 2025; as the first triple amputee to sail solo across any ocean; and also, specifically the Pacific Ocean. In 2009, aged 18, the former British Army rifleman lost both legs and his left hand when he was blown up in Afghanistan. He found salvation through sailing and is RYA Yachtmaster qualified. Craig’s book Finding my Sea Legs, co-written with Amy Willis, is now on sale.

Triple amputee Craig Wood prepares for 80 day solo Pacific crossing

Triple amputee Craig Wood is gearing up for a world record setting solo voyage across the Pacific to change perceptions…

Left for dead after falling overboard: how one sailor survived 5 hours lost at sea before rescue

Roger Cottle was presumed dead after falling overboard a 27ft yacht and lost at sea for five-and-a-half hours in a…

15 boat fixes at sea: sailors share how to deal with torn sails, rudder damage, chafe & more

Transatlantic sailors tell Ali Wood how they used their ingenuity – and sometimes bravery – to cope with emergencies on…

Satellite communication at sea: staying connected from your boat

With Starlink’s high-speed internet, do sailors still need satellite phones on board while at sea? Ali Wood looks at the…

Want to read more articles about adventurous sailors like Craig Wood?

A subscription to Practical Boat Owner magazine costs around 40% less than the cover price.

Print and digital editions are available through Magazines Direct – where you can also find the latest deals.

PBO is packed with information to help you get the most from boat ownership – whether sail or power.

-

-

-

- Take your DIY skills to the next level with trusted advice on boat maintenance and repairs

- Impartial, in-depth gear reviews

- Practical cruising tips for making the most of your time afloat

-

-

Follow us on Facebook, Instagram, TikTok and Twitter