Frank Sibly encounters tombstoning teenagers and other navigational hazards on a hop along the north Cornish coast

My wife, Sue, and I had been thinking about cruising the north Cornish coast on our trailer-sailer for the last decade, despite Mark Fishwick’s opinion in his West Country Cruising guide that there’s little real cruising potential on this dangerous stretch of coast.

Admittedly, it’s probably not suitable for bigger yachts. However, having visited many minor harbours with the former Trail Sail Association aboard Coast-inn, our lift-keel Etap 22i, we thought we would give it a go. After all, Fishwick does say: “Just possibly, in very settled weather, and with an offshore wind, a little bit of cruising can be contemplated.”

We planned the trip for mid-July – before the school holidays, thinking (wrongly) it would be less busy. It never gets completely dark at this time of year, and we’d definitely have enough light to navigate by from 0530 until 2100. Also, the swell coming in from the Atlantic would be less than it would late August after the American hurricane season.

Each leg would best be done in daylight with the wind and tide. When we checked the forecast before leaving, it showed more south-west than not, so we needed a north-east flowing tide, which starts near low water in this part of the coast. Had the forecast been northerly or easterly winds (which surprisingly occurs for 30% of the time according to a Met Office paper), we would have reversed direction.

We decided to start in St Ives (there are no ports west of here), so checked boatlaunch.co.uk and Google satellite images.

However, we quickly realised that it would be impossible to launch a trailer-sailer from the slip at St Ives as it needs two hours of setting-up and the streets are narrow and busy to negotiate.

Instead, we chose neighbouring Hayle. Although Reeds doesn’t advise it for yachts, it was great for our purpose, so we paid our £15 launch fee to the harbourmaster at the Old Customs House. As the start of the slipway was under an electricity cable we had to manoeuvre the boat part-way along the slip before raising the mast.

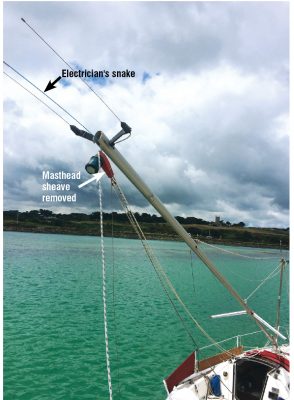

We moored alongside the quay wall, but then found a halyard had disappeared up the mast. Fortunately, the assistant harbourmaster Ben happened to be in a nearby shed, building a Wharram Tiki 21 catamaran with his aptly named partner, Kat. Though it was his day off, he kindly leant me an electrician’s snake, which we used to feed the halyard back down the partly lowered mast. I resolved to add this instrument to my onboard tool kit from now on.

In a trailer sailer, you can get to a missing halyard by lowering the mast, taking the sheave off, and running up an electrician’s snake.

Parking is now something that has to be planned on any trailer boat cruise – long gone are the days when you could just park on a quayside or a lay-by for free. We took the car and trailer to a field on the outskirts of Padstow where Trevethen Farm has diversified by having a car park.

We caught the bus back, and as it was too late to set sail that day, enjoyed a Cornish pasty at Philp’s family bakery, which we chose because of the long queues outside. We had a coffee at ASDA and used the loos as there were none at the harbour itself. The harbourmaster told us of plans to convert the extensive derelict quays into holiday apartments and a marina, which will bring in a lot of much-needed local employment.

It wasn’t straightforward leaving Hayle, as there was no channel marker at the time (though this has since been reinstalled) and only sufficient water over the bar one hour either side of high water.

Fortunately, the helpful owner of the Eskinzo Surf School had taken photos with his drone, showing the line of the channel. We just needed to follow the posts on the north-going training wall and veer about 25° to the east.

In the event, we spotted a local boat departing shortly after us, so we slowed to allow it to overtake, and then followed. A short sail of three miles took us to St Ives, and we telephoned the harbourmaster, but the wind made us inaudible on the phone, so we were advised to use VHF Ch12).

Having dodged the paddleborders zigzagging across the entrance, we picked up one of the white fore-and-aft visitor moorings and went ashore.

Shoreside fun in St Ives

First mate, Sue, tolerates the sailing if there’s the chance to visit an open garden, or a good restaurant, so after going to the Tate St Ives art gallery, we took a delicious dinner at the Portminster Beach café, watching the branch line trains go by. After dinner, we walked back to the boat as by now the harbour had dried out.

We woke at 4am the next morning to leave before the harbour dried out again.

We anchored just outside the entrance in about 6m, with a cluster of fishing vessels which had their anchor lights on. Failing to get back to sleep because of the rolling motion, we lifted anchor and tacked out of the bay, heading round the Stones north cardinal 1¾ miles off Godrevy Point, and onto Portreath (10 miles). We managed 5½ knots over the ground, which is fast for us, but caused us to reach Portreath too early, so we hove-to.

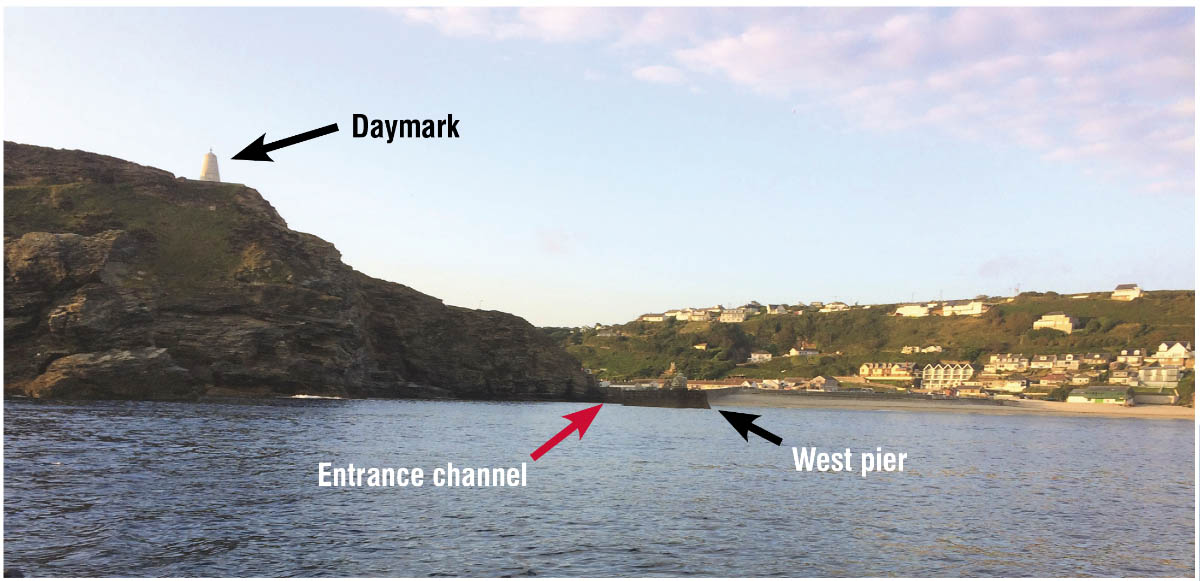

Portreath Harbour entrance. The black arrow shows the end of the West pier. The channel is hidden from seaward but runs where the red arrow is. The white daymark is on the cliff to the left.

Looking at the cliffs, I wondered if we were in the correct place, as I could see no entrance through them. My handheld Garmin chartplotter gave me reassurance, but it was hair-raising nonetheless, as we sailed towards the cliff, with offlying rocks, and no obvious way in.

Following the instructions in the Lundy and Irish Sea Pilot, we saw the south pier with a short concrete tower on its end, and kept that slightly open, to keep us off the reef on the southern side of the entrance. It wasn’t until well inside that we could see a way round the cliffs and into the harbour proper.

To make matters worse, the narrowest point in the harbour was used by teenagers jumping into the water, which is unnerving when navigation is so difficult!

Yet, despite my reservations, it turns out that right up until the 1960s, 280-ton coastal packet ships entered Portreath harbour bringing coal from South Wales.

Nevertheless, I was glad that my brother was following our position on the RYA Safetrx app, and was ready to call for help if we failed to arrive by our ETA. The app is a reassuring measure for any small craft on a hostile coastline.

The following day the wind was against us, so we got out the folding Brompton bikes from the forepeak, and cycled to an open garden in Redruth.

Afterwards, we spent a happy afternoon in the Porthreath Arms watching the Wimbledon tennis final. The pub provided splendid hospitality, with a drop-down screen and projector, and fine ale and dinner for the skipper and crew.

Busy Newquay

The next morning I slipped our mooring at HW+2, leaving Sue to walk the South West coastal path while I headed for Newquay 16 miles away. Sue would then catch the bus and meet me there.

There being no anchorage in the vicinity of Portreath, I headed against the tide, staying clear of St Agnes Head, and the Bawden Rocks lying a mile offshore.

Cockpit when singlehanded: chart in waterproof cover, voyage plan notebook, VHF on hinged bar in companionway

Now single-handed, I made preparations for solo sailing before departure, with food ready, kettle filled, chart on deck within a chart cover, and autohelm ready to take over for short periods.

Newquay harbour was packed with fishing vessels and tourist boats. We were eventually squeezed into a gap between two huge fishing boats, but couldn’t stop ourselves moving forward onto the hull of the fishing boat in front.

There were loos on the quayside, and the rowing club provided showers in return for a donation. It turned out to be the biggest Pilot Gig club in Cornwall, and had a great bar. We felt Newquay town itself had seen better days, but we walked 15 minutes to Fistral beach, and had a drink in the magnificent Edwardian Headland Hotel. Back at the quay, we ate at the charming Boathouse, which allowed us to keep an eye on the boat.

I hadn’t deployed the yacht legs, and the sand was firm, so she tilted on the stub bulb of her lift keel, bringing the mast rather closer to the quay wall than I would have liked!

Although weak winds were forecast we felt the harbour was too full for us to stay another day, so we headed 16 miles to Padstow.

We motored a few miles before there was enough breeze. Even so, the tide was against us as we passed between the Bull and the Quies rocks off Trevose Head, and it took more than an hour to get round the headland. We weren’t in a hurry, though, because we couldn’t enter the River Camel until two hours after HW.

The outer part of the channel wasn’t marked, but we continued eastward until the first red buoy was more than 180°, which kept us away from the sandbank of Doom Bar, which extends halfway across the entrance from the west. The rest of the channel is well marked, but it was still too early for the inner harbour tidal gate, so the Harbour Patrol (who principally keep an eye on speeding motorboats) suggested picking up a vacant mooring.

I was caught out by the force of the flood at LW+3, and had difficulty picking up the mooring, despite being in the cockpit, and using a boathook. When the tidal gate was finally hinged down at HW-2 we entered, together with a yacht from France and three others from South Wales.

Padstow harbour is small, and there’s no space in the outer harbour (which is for commercial boats) so we had to raft up.

Though there’s plenty of fine dining available in Padstow, it all gets booked up a long time in advance. However, we did manage a breakfast at Rick Stein’s the following morning before retrieving the boat to the trailer ready for the drive home.

Once home we emailed Reeds and Visit My Harbour with a few facts that needed updating, probably because these harbours are so rarely used by visitors.

About the author

Surgeon Frank Sibly started sailing at the age of 13 in a Heron dinghy on the Warwickshire Avon. His first time on a yacht was crossing the Channel with the Island Cruising Club in Salcombe, in a wooden North 26. He bought a Skipper 17 before later changing to an Etap 22i.

Surgeon Frank Sibly started sailing at the age of 13 in a Heron dinghy on the Warwickshire Avon. His first time on a yacht was crossing the Channel with the Island Cruising Club in Salcombe, in a wooden North 26. He bought a Skipper 17 before later changing to an Etap 22i.