Julia Jones looks at the lives of Peter Gerard, Clare Allcard and Rozelle Raynes, notable 20th century sailors and boat owners

When I was a child, reading on board Peter Duck, I became obsessed with Ten Small Yachts, Maurice Griffiths’s second book, published in 1933 following the success of Magic of the Swatchways. I was both fascinated and appalled by the frequency with which he changed his boats: Iduna, Vahan, Albatross, Wild Lone, Swan, Storm, Puffin II, Afrin, Wilful, Afrina, Nightfall.

Griffiths’ evocative writing encouraged me to lose my heart to every one of the vessels on his list, however cumbersome, leaky, tender or unhandy she might be. I felt their personalities and couldn’t comprehend the callous way with which he sent each one on her way at the end of every season.

I wholeheartedly endorsed the alternative approach of his then wife, Dulcie Kennard (who wrote under the name of Peter Gerard), who found her own Juanita and remained faithful until her life’s end. For a young married couple to diversify into separate craft caused some gossip. Peter resented this.

Peter Gerard (left) sailing with a cadet aboard the Falmouth-built Juanita. Credit: Peter Gerard

‘No one is surprised if a modern wife flies her own light aeroplane, rides her own horse or has a separate car, yet because a boat with a lid on it acquires some of the characteristics of a shore residence, they regard it with the same concern that might be shown on hearing that a happily married pair lived in separate flats,’ she wrote. They’d been living on board the ex-pilot cutter, Afrin, and sailing her keenly at weekends.

Peter worked hard to make Afrin a snug home, but knew it would not be long before Griffiths would be on the lookout for something new. In Ten Small Yachts, Griffiths offers a reasonable explanation for his frequent changes: ‘I am cursed with a critical mind and have therefore always been ready to note the failings as well as the virtues of these lovable little craft.’ Whether consciously or unconsciously, in these early years he was developing himself as a designer, ‘the more boats one owns, the more ideas one cultivates’.

Independent Ownership

Peter was not a blind sentimentalist. She had clear ideas about the qualities she wanted in a yacht and also about the way they should be maintained. She wanted to be able to put her ideas into practice ‘without having to go into conference’.

She was prepared to work hard – as their wooden boats demanded – but needed the security of knowing that when she had a vessel customised in a way that suited her ‘orderly spirit’, that it wouldn’t suddenly be whisked away by Maurice’s decision to sell. ‘What happens when one partner wants to sell and the other does not?’ asked Peter. ‘Obviously someone has to wipe away a tear and capitulate.’ In her experience, this was usually the woman.

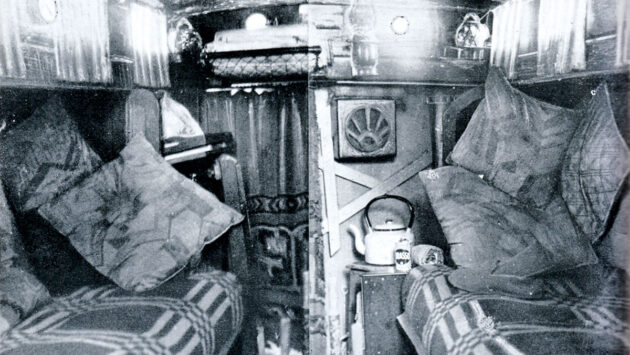

Juanita‘s saloon. Peter Gerard customised her boat to meet her needs and was determined to make it homely. Credit: Peter Gerard

As a young reader, I thrilled to Peter Gerard’s bold independence. Her Juanita had a romance and even a swagger about her that was lacking from many of the other vessels in Griffiths’s book. She was presented as a deep sea voyager, with a bold sheer, a high bow, a deep keel and a counter stern that captured my imagination.

Wood is adaptable: sections can be sawn off or added on. Juanita had originally been built in Falmouth as a quay punt, and I had no idea then that her counter stern, that gave her such a long sweeping line, was a later addition, as was the fully enclosed cabin which Peter made so snug and in which she instructed other women in the arts of navigation and seamanship.

After Peter Gerard’s death, Juanita fell into disrepair before being discovered in the Felixstore Ferry boatyard with both her counter stern and cabin top removed. Credit: Janet Harber

Many years later, when Peter was dead, and my friend Janet Harber took photos of Juanita looking forlorn in Felixstowe Ferry boatyard, with both her counter stern and cabin top removed, we found it hard to believe that this was the same yacht. Wooden yachts, lovingly maintained, can long outlast their human owners, but difficulties arise when the owner loses the physical capacity to keep up the necessary work.

Peter and Maurice’s marriage didn’t last, but in her second, very happy marriage to marine artist Charles Pears, she found a husband who was not in the least threatened by her fidelity to Juanita, because he too had a vessel, Wanderer, from which he had no intention of parting. During World War II, Peter and Charles moved to Cornwall, Juanita’s original home. He died, she aged, and there were too many years when her yacht remained propped up on legs on the beach.

Juanita is still being actively raced, pictured here in Falmouth. Credit: Nigel Sharp

In 1980, Juanita toppled over. Peter died shortly afterwards. It was Juanita’s good fortune that she was back in the county of her birth, and knowledgeable enthusiasts came forward with the skills and motivation to convert her back to a quay punt.

Clare Allcard: relationship building

When Clare Thompson was ‘rescued’ from St Francis mental hospital in Haywards Heath by solo circumnavigator Edward Allcard in 1968, she and their daughter, Kate, spent several years following him and his then yacht Sea Wanderer as they completed their slow circling of the globe.

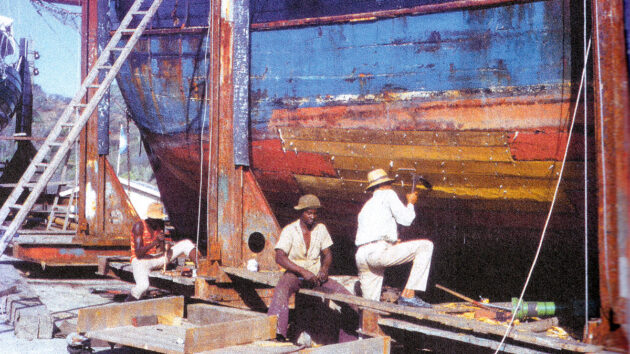

In 1974, when Allcard spotted the Baltic ketch that would become Johanne Regina on the slipway in Antigua, he saw her as fulfilling his private dream to recreate Columbus’s La Niña: Clare Allcard saw her as their potential home. Edward sold Sea Wanderer and bought the filthy, leaking, worm-bored, rat- and cockroach-infested, semi-derelict 69ft ketch with 18ft bowsprit, 6ft 8in draught, black, stinking bilges and enormous, almost terminally seized Gardner engine.

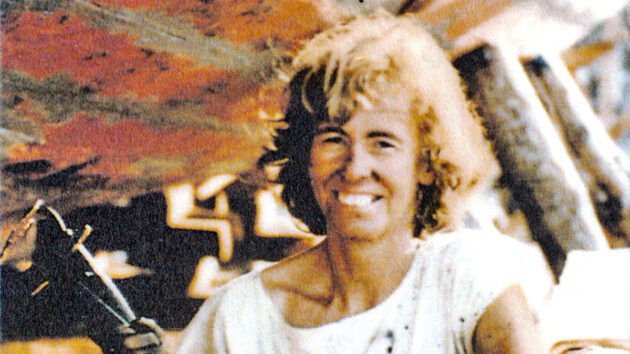

Clare Allcard got stuck in to the restoration of Johanne Regina. Credit: Clare Allcard

Clare now needed to find ways to ensure Johanne would truly be her and Katy’s home in a way that Sea Wanderer never was. This involved some difficult decisions. The choice of immediately enrolling Katy in an island kindergarten so that Clare could get on with scrubbing, scavenging and refurbishing was a no-brainer.

Johanne was, in Clare’s words ‘a dangerous shambles’. On their very first day of ownership, five-year-old Katy tripped and fell onto the rim of a rusty ventilator, necessitating seven stitches in her forehead. When, with extraordinary skill, dedication and hard work, Johanne was returned to seaworthiness, Katy was discovered to be incurably seasick.

Although she never complained, Clare Allcard became increasingly anxious as the prospect of an Atlantic crossing loomed. It would be dangerous for Katy to undertake this voyage when unchecked sickness, perhaps lasting days or weeks, could cause irreversible dehydration. She would need to cross by air.

The Baltic trading ketch Johanne Regina is now the sail training ship of the City of Badalona. Credit: Ciutat Badalona

But what should Clare do? Many mothers would resignedly have decided that they must accompany their child, but Clare believed that sitting out a sailing challenge like this would mean that Johanne would inevitably become Edward’s boat, where she and Katy would once again be visitors as they had been on Sea Wanderer. All the cleaning and maintenance in the world is not enough to form a relationship with a boat without actually sailing. It’s then they come to life.

Clare Allcard was a completely inexperienced sailor, but she needed to stand her watches and do this crossing. She was lucky that her parents understood and came over from England to take charge of their granddaughter. Today, Clare recalls the specific moment she finally felt Johanne Regina was hers.

“She was 98ft long if you count the bowsprit. All sails set. Me totally alone at the helm. Sun setting and a line squall on the horizon heading towards us and, for the first time, I decided to ‘do it alone’ and not call Edward for help.

“I watched the rain pounding on the sea, the white crests whipped up by the wind advancing towards me as I gently eased the bow to port to catch the full force of the wind on the jibs and main. And then the amazing exhilaration when the wind struck and 99 tons of ancient oak leaped forward across the ocean, and we charged towards the setting sun. And I was in control.”

Replanking of Johanne Regina. Credit: Clare Allcard

The time eventually came when they needed to move ashore and make the difficult decisions about the future welfare of Johanne Regina. She was handed to the Spanish city of Badalona as their sail training ship. Today, Clare Allcard remains in contact as an honorary godmother. When a new tender was purchased recently, the Amics del Quetx, Ciutat de Badalona, who manage and maintain the ship, named it Katy, after Clare and Edward’s daughter.

A Means Of Escape

Buying a boat of her own was a more straightforward proposition for Lady Rozelle Beattie after her father died and she inherited his estates. Rozelle had been obsessed with the sea from early childhood, but life had been in London or in Nottinghamshire, and there was no other nautical interest in the family. Joining the Women’s Royal Navy Service (WRNS) in the latter part of World War II had given her first opportunities to experience the thrill of boat handling.

Once demobbed, she had to fight hard not to be forced into the life of a debutante. A disastrous experience as a yacht hand persuaded her parents that she should be allowed a boat of her own, but money was tight, and there was no one to offer advice. Rozelle spent several years surviving a series of tricky situations as she attempted ambitious North Sea crossings in Imp, a small and leaky motorboat with an unreliable engine. After Imp was finally wrecked on a lee shore in Belgium, Rozelle realised she needed to learn to sail.

Careful Choice

By this time, she could afford to look around carefully and pick a suitable yacht of good quality. Her choice eventually fell on Martha McGilda, an engineless 25ft Folkboat built by Chippendales of Warsash. Martha was being sold by racing yachtsman Noel Jordan and had just won the East Anglian Offshore Championship.

Although Noel wanted a slightly larger vessel, he wasn’t finding it easy to part and willingly agreed to remain in touch and teach Rozelle how to handle this quick, responsive little ship. Noel Jordon’s influence was such that Rozelle continued to consult him mentally when presented with a tricky problem of navigation or seamanship.

Rozelle Raynes with her Tuesday Boys. Credit: Thoresby Settlement

In The Sea Bird, she recalls an incident where she was in a highly dangerous situation, in the dark, off the Casquets, failing to find the entrance to Braye Harbour. ‘Suddenly a voice – perhaps Noel Jordan’s – seemed to say to me “Stop being a plumb stuffed idiot. Get out to sea and wait for dawn to break and the tide to turn; then at least you might be able to see where the entrance lies.”’

Rozelle had married, but it was not a success. It was fortunate her husband, Alexander Beattie, had no interest in sailing as this made it easier for her to escape ‘the problems of the land’ by sailing Martha single-handed, further and further away.

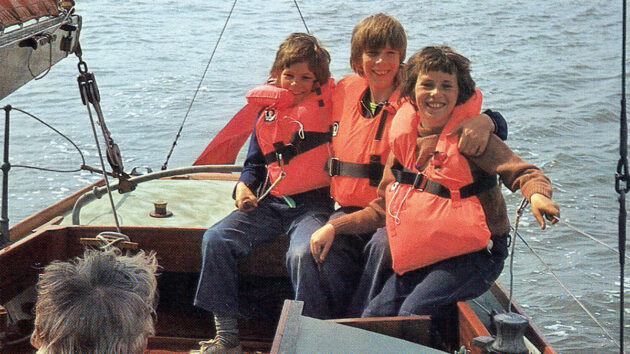

Tuesday Boys enjoying a first sail down Gallions Reach aboard Martha McGilda. Credit: Thoresby Settlement

In 1959, when she was evidently considering a divorce, she sailed single-handed to the Gulf of Bothnia, with only a Seagull outboard to get her and her little yacht out of trouble. Her boat was her escape route, her challenge and her companion.

She fell in love with and married a fellow sailor, Dr Richard Raynes. Dick was happy to sail with her in Martha, but gradually what was snug for one became cramped for two, particularly as they usually also sailed with a large dog. A roomier cruising yacht, Roskilde was built, and there began to be talk of selling Martha.

In Rozelle’s perception, the little boat began acting up – she split her mainsail, ran aground, hit Dick on the head with her boom. Or was it Rozelle herself who could not bear to part? Martha might have returned to Noel Jordon but he died, unexpectedly, leaving his widow, Ursula, with a third share.

Ursula didn’t want to sell either. Instead, they found a new purpose for Martha, relocating her to the Royal Albert Docks, where Rozelle then spent every Tuesday teaching sailing and seamanship to a group of eight young boys living in a Newham children’s Home. It was a relationship with a two or possibly three-way benefit.

Martha McGilda is still regularly sailed (as all wooden boats need to be), including on the Walton Backwaters. Credit: Chris Titchmarsh

The little yacht settled down, the boys learned unexpected skills, and so did the regretfully childless Rozelle: ‘I had often wondered what it would feel like to have the boat full of children spilling coke and crumbs all over the decks and swinging like monkeys from the boom; and now I knew…’ Rozelle and Dick aged. The ‘Tuesday Boys’ grew up and moved on. Roskilde was sold, and Dick died. But Martha was not to be sold.

What was to happen to her? Rozelle’s solution was to gift the yacht to a shipwright from the Dover yard that had taken on her care, together with a sum of money sufficient for her maintenance. But the shipwright wasn’t a sailor, and wooden boats must be used to stay well.

After hearing of Rozelle’s death in 2015, Essex marina owner Chris Titchmarsh who, as a boy, had watched both Martha and Roskilde bought round gleaming every spring to his father’s marina in Walton-on-the-Naze, went down to Dover to see whether he could discover what had happened to Martha. He was not at first successful, but a few weeks later a call from a friendly broker led him to discover Martha, dingy and forgotten, leaning against a wall in Dover harbour.

Chris Titchmarsh with a souvenir from Martha McGilda. Credit: Chris Titchmarsh

She was ‘not to be sold’, but some form of words was agreed to allow Chris to become her ’custodian’, bring her back to Essex and restore her to her former immaculate condition. Chris Titchmarsh gains deep satisfaction from keeping Martha almost exactly as she was in Rozelle’s ownership.

He has recently invited the former ‘Tuesday Boys’ to visit and renew their acquaintance not just with her but with Roskilde, which was about to be destroyed by Exeter City Council over unpaid mooring fees. Juanita is introducing a new generation to quay punt racing in Falmouth, and Joanne Regina is training young people in Badalona. Their stories go on.

Ann Davison: transatlantic first

Ann Davison became the first woman to sail across the Atlantic solo when she arrived in Dominica in January 1953.…

The pioneering sailor you’ve probably never heard of: Nicolette Milnes Walker

Nicolette Milnes Walker was the first woman to sail solo and non-stop from the UK to the USA. Julia Jones…

Making history in an Albin Vega 27 – Jazz Turner’s story

Adventurer and disabled sailor Jazz Turner reflects on her recent record-setting UK and Ireland circumnavigation

Hanneke Boon: Life after Wharram

Ali Wood learns how a shy 19-year-old – one of James Wharram’s ‘five girls’ – became a designer, skipper and…

Want to read more articles like Clare Allcard. Rozelle Raynes & Peter Gerard: how these three sailors found independence through their wooden boats?

A subscription to Practical Boat Owner magazine costs around 40% less than the cover price.

Print and digital editions are available through Magazines Direct – where you can also find the latest deals.

PBO is packed with information to help you get the most from boat ownership – whether sail or power.

-

-

-

- Take your DIY skills to the next level with trusted advice on boat maintenance and repairs

- Impartial, in-depth gear reviews

- Practical cruising tips for making the most of your time afloat

-

-

Follow us on Facebook, Instagram, TikTok and Twitter