What is a transit? Dick Everitt explains how lining up a pair of appropriate land features or navigation marks can help keep you safe

Transits are when two navigation marks line up and give a very accurate position line – just like when you align the front and back sights of a rifle. It’s a really simple navigation technique that’s been used by sailors for centuries, writes Dick Everitt.

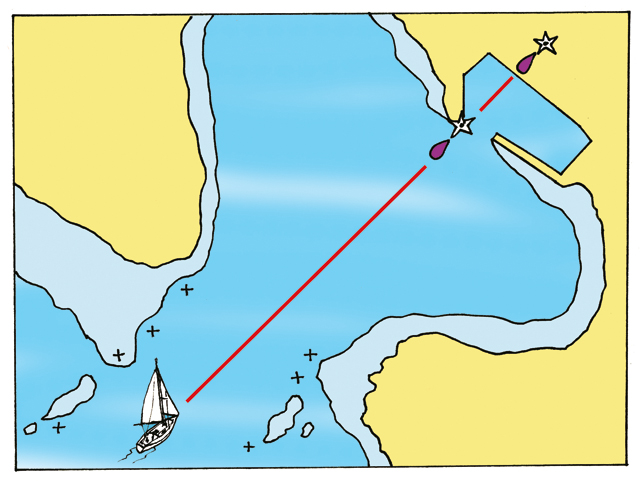

The most common types of transits are leading marks that guide you into tricky harbour entrances. Just aim the boat at the two marks, and keep everything in line to compensate for any strong crosswinds or currents. These marks come in all shapes and sizes, ranging from massive towers and buildings painted a distinctive colour, to tiny shapes overgrown with foliage and small grubby buoys in the water. At night there are often leading lights to do the same job.

Pilot books and charts list leading marks and often give their bearing towards the land in degrees true (°T), so you’ll need to convert this for your compass to see if you’re on the right track. Some marks can be very awkward to pick out at long range – a good pair of marine binoculars will help and the ones with a built-in compass also let you check the bearing at the same time. You could input a mark’s GPS position, or whack in a waypoint with a chart plotter, but do make sure you have up-to-date electronic cartography as sandy shoals can shift quite quickly and the marks get moved often.

If in doubt, don’t

It’s also crucial to make sure you are looking at the right marks. Don’t go ahead hoping to see the correct one soon! If in doubt, stay out and call the harbour master for advice. Here are two close shave stories to emphasise that point:

1) A boat was closing a remote coast on a moonless night, and the skipper knew exactly where he was with GPS – but couldn’t see the leading lights. He’d planned to be in harbour that night, but because he couldn’t contact anyone ashore and ‘felt’ something was wrong, he decided to spend another night at sea – which wasn’t popular with the crew. However, in the morning they saw a ship had sunk across the channel, obscuring the leading lights, and they could have sailed right into her!

2) A boat was entering a coral lagoon at night. The skipper saw both the leading lights that he was expecting, but noticed that the leading lights’ bearing wasn’t right. A call ashore confirmed that the rear leading light was out of order. He was lining up the lower leading light with a masthead light of a yacht anchored in the a lagoon – and heading straight for the reef!

Line ’em up

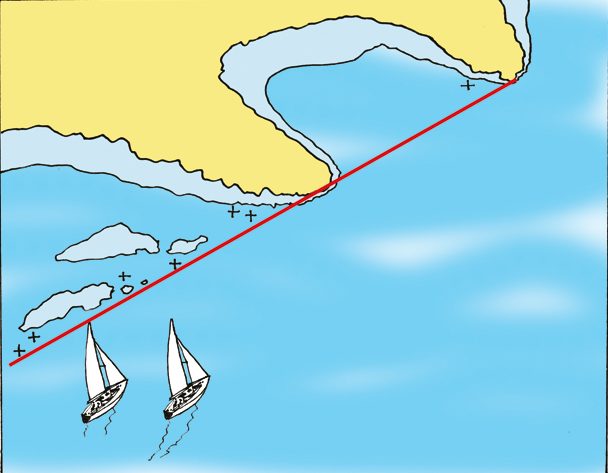

Earlier in this series we covered what is a clearing bearing and, often, you can find transits to do the same job. The classic example is to use two well-defined headlands. If you keep the headlands in line, then you are on that position line, and know you are not being set into the bay.

But, as it’s hard to judge when headlands are in line, just make sure you can see both headlands and keep the next bay ‘open’. Then you know you’re in safe water. If the bay ahead starts to ‘close’ you’ll need to head out to sea a bit. These pilot book terms ‘open’ and ‘closed’ are explained more clearly in the diagram (below).

A look at any coastal chart will show up loads of potential transits that can give a quick eyeball position line. You can line up mountaintops, radio masts, chimneys, ends ofpiers, and buoys (but do remember that buoys move a bit in the tide). It’s a handy skill to develop, so you can see where you are without always having to rely on GPS.

Transits are also a good check to see if your anchor’s dragging. Once the hook’s down make your own transits by lining up a tree, bush or rock and see if they move relative to each other.

Transits also help to judge how fast you are blowing sideways when docking in strong winds. You won’t find a proper transit to line up with your exact approach angle, but judging how fast the gap between any vertical marks closes will give you a fair idea of your sideways movement.

Using two well-defined headlands

The photograph shows that the gap between the headlands is nearly closed. A safer position would be further out to sea in this case, as illustrated below.

The view from the boat futher out to sea shows the gap between the headlands is much more open, so we’re well clear of any hazards

Using a pair of leading lights

The hard sell…

Do you know any young boaters or people who dream of owning a boat one day? A recommendation from you to start reading PBO could save them money in the long run and means our experts can continue helping all boat owners with their problems.

Subscribe, or make a gift for someone else, and you’ll always save at least 30% compared to newsstand prices.

See the latest PBO subscription deals on magazinesdirect.com