Abandoned wrecks and end-of-life vessels hogging cheap moorings and clogging up Britain’s foreshores are a growing problem and environmental concern, agree harbour authorities, sailors and community groups.

The issue and associated costs are expected to escalate in the next decade as we are dealing with “a glut of vessels from the 1960s and 70s coming to end of life at the same time as boats from the 80s and 90s,” warns deputy harbour master Rob Dunford at Langstone Harbour in Hampshire.

Modern trends are likely to see the current 20ft-something glass fibre-reinforced polyester resin (GRP) yachts and cuddy fishing boats rotting in boat yards, ashore and afloat, over time being replaced with larger vessels that require specialist transport or Environment Agency (EA) permits to break apart in situ.

Jake Burnyeat, the founder of the Wreck Free Fal and Helford forum, bringing together the groups tackling the issue in the Falmouth area, said: “If you fast forward 10, 20 years, production volumes have gone up and boats got bigger, just like cars, so that if we don’t do anything, our foreshores are going to be lined with 30-something foot yachts.

“When a car reaches the end of its life you can take it to a scrapyard, get paid a few hundred pounds, and it will get recycled.

“It costs a lot of money to dispose of a boat responsibly so sadly they often get left in the corner of a creek to die; leaking toxic paints, oils and microplastics into the ocean.”

Lack of recycling options for abandoned boats

A yacht that broke its mooring bridle and was subsequently abandoned by its owner. Credit: Langstone Harbour

Volunteers have been clearing wrecked abandoned boats and a van from Helford and Fal estuaries. Credit: Clean Ocean Sailing

According to a 2016 study by the OSPAR (Oslo and Paris Conventions) commission, where 15 Governments and the European Union co-operate to protect the marine environment in the north-east Atlantic, 1-2% (60,000-120,000) of recreational boats in Europe reach the end of their life each year.

Most ‘dead’ GRP vessels end up in landfill due to the lack of recycling options.

The cost of disposal can be around £1,500 or more for a three-tonne boat.

Pollution concerns include glassfibre causing ‘asbestos-like’ damage to organisms such as oysters and mussels, plus microplastics, diesel oil and paint leaching into the seas.

The boating community also loses out “as the cost borne by harbour authorities means it is becoming a disincentive to facilitate the more cost-effective moorings in and around our harbours,” warns Langstone harbour master Billy Johnson, as these cheaper moorings are where many end-of-life vessels tend to be abandoned.

The local harbour user and/or the taxpayer also usually pay for the wrecked and abandoned vessels going straight to landfill.

Of 120 problem boats on “mainly Eastney foreshore” in 2022: “two remain, 76 were removed by the harbour board. Two were impounded and sold.

The remainder were repaired and returned to their moorings by the owner. Portsmouth City Council also removed 30-40 boats.

Johnson said: “This is a massive issue for us along with many other harbour authorities.”

Langstone Harbour Board has temporarily suspended issuing new private mud mooring licenses, as many of these very cheap moorings, installed and maintained by the individual, were failing due to poor maintenance and vessels ending up on the beach, or left abandoned on the moorings.

Dunford said: “We hope to find a middle-ground where grass-roots boating from mud moorings can be made available in Langstone without the environmental and financial detriment to the harbour.”

He added: “We have also seen a concerning increase in people living rough on totally inappropriate and unsafe end-of-life vessels on the beach.”

The Langstone Harbour team corral a batch of end-of-life vessels ready for removal – these ones by Marine & Boat Recycling. Credit: Langstone Harbour

‘A great shame’

“There’s a pressing need for a national framework for end-of-life vessels,” said Emma McGee, director of the Sailors Creek Community Interest Company (CIC), based near Flushing in Cornwall, which has removed nine end-of-life vessels and more than 57 tonnes of flotsam, jetsam and marine waste from the creek over the past five years.

Johnson agrees: “I’d like to see a national requirement for vessel registration, even if it were only the requirement to register with a local harbour authority, as well as a requirement for adequate insurance be introduced.

“We certainly see a trend where end-of-life vessels are bought and sold at knockdown prices, often to individuals who have little understanding of what they are getting into, until sooner or later no owner can be identified, and the now poorly maintained vessel is simply a problem for the harbour authority to resolve.”

He added: “Certainly, a regional response to this issue would be a positive step, but that is always going to be tricky in the UK ports landscape which is much more fragmented than the continent.”

Don’t let the abandoned boats sink

‘Keep it an ‘afloaty-boaty’ – Langstone Harbour deputy harbour master Rob Dunford warns that sunken boats cost about 75% more to dispose of. Credit: Langstone Harbour

Dunford’s practical advice to harbours, marinas and local authorities is “crack on – deal with it while it is still an afloaty-boaty because sunken boats cost about 75% more to dispose of.”

He said: “I have disposed of four insured vessels in the last two years. In no instance did the insurers pay out for wreck removal, stating that it was the owner’s responsibility because they were at fault.”

Scrapyard sites should be incentivised to reduce landfill by recycling or sending waste to energy and “would be well placed for dealing with the influx of end-of-life turbine blades from offshore wind farms too,” added Dunford.

Tracking the issue is also “really important”, and he said harbour authorities have been calling for The Green Blue – the joint environment programme developed by the Royal Yachting Association (RYA) and British Marine –to make its wreck reportage system register open access, which it has now done (and this data is available upon request).

Dunford believes boat-sharing schemes could help, and “manufacturers should be encouraged through regulation” to make vessels more repairable and recyclable.

He added: “I think it is time for the Government and industry including the UK Harbour Masters’ Association, British Ports Association, British Marine, Composites UK, RYA and local government to work this through.”

Cost conundrum

Jake Burnyeat, a volunteer who set up the Wreck Free Fal and Helford forum at its launch event. Credit: Clean Ocean Sailing

The Wreck Free Fal and Helford forum highlights the French model, which is “successfully tackling the problem with 35 free-at-use scrappage yards around the coast where 11,000 end-of-life boats have been scrapped since 2019”.

France has a national boat registration scheme and its scrappage scheme is paid for by a producer levy on new boats and an annual boat tax, which also funds its lifeboat service.

“Free use recycling is the main thing, compulsory registration and boat tax may sound contrary to the British freedom of the seas principle.

“But look to France, where sailing is a far more democratic sport than in the UK, more people have boats in France, so it clearly doesn’t put them off,” said Burnyeat.

“We estimate £150,000 a year is needed to enable free-at-use boat recycling for the predicted pipeline of boats reaching the end of their lives on Helford and Fal estuaries.

“That could be funded by an average voluntary £30 contribution from each of the 5,000 moorings, grants and contributions from foreshore owners and stakeholders.”

However, Christopher Jones, maritime manager at Cornwall Council, which has removed 74 problem vessels from its 10 ports and harbours since 2015, said: “I do not agree that our mooring holders should fund disposal of boats in non-statutory harbour areas.

“Our harbour users are already paying for the disposal of vessels within our statutory areas, along with our other conservancy functions. We have an appropriate budget allocated for the removal of such vessels.”

Consolidating all its harbours legislation into one Harbour Order two years ago increased powers to remove such vessels; Article 61 of The Cornwall Harbour Harbour Revision Order.

More disposals are planned for this financial year.

Jones said the new legislation coupled with “proactive action by the Harbour Management” was reducing the problem within its Statutory Harbour Areas (SHA).

He added: “Where I do have concern is with areas, such as the Helford, that are not within an SHA.

“As the harbours become more proactive those areas become vulnerable to the abandonment of boats.”

Dunford agrees it is unfair to put the burden “on responsible owners”. He added: “A charge on new builds could reasonably be expected to sustainably cover those from the last 25 years coming up for disposal.”

An abandoned boat on its mooring at Stonehouse Bridge, Plymouth. Credit John Summerscales

Aerial view of boats, including some abandoned wrecks, in a Falmouth area estuary. Credit: Clean Ocean Sailing

Protected site

In Merseyside on the North West coast, abandoned boats left on Heswall foreshore on the Dee Estuary, a designated Special Protection Area (SPA) and a Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) due to its important habitat and bird populations, has caused the council to step up security measures.

A Wirral Council spokesperson said: “The concerns are that abandoned boats pose a pollution risk as they deteriorate and release oils, paints and plastics into the environment.

“This poses a risk of harm to wildlife and a detrimental effect on the wider habitat.

“Wirral Council, as the landowner, has a legal duty to manage and control the foreshore and has worked with other agencies, such as Natural England and the Marine Management Organisation (MMO) to remove abandoned boats.”

The council has installed an electronic barrier gate and a closed-circuit television (CCTV) system to prevent unauthorised access to the foreshore, and has also engaged a specialist consultant to tackle the issue.

‘Polluter pays’ principle

Abandoned boats can leach hazardous chemicals such as paint, diesel, litter and microplastics into the marine environment – and also attract vandals. Credit: Langstone Harbour

Abandoned boat at Truro River. Credit: John Summerscales

In 2023, the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (DEFRA) appointed consultants to conduct research into end-of-life recreational boats, who concluded that “quantifying waste arisings” was “crucial”, recommending site visits to harbours and boating clubs and mandatory vessel registration.

The Environment Agency, which reports into DEFRA, will intervene in boat removal only if it presents a significant hazard, flood- or pollution-risk.

An Environment Agency spokesman said: “We always welcome information from the public about boats or debris that may pose a risk to navigation or increase flood risk.

“We ask anyone who spots a potential blockage or pollution in a river to contact us on our 24-hour hotline, 0800 80 70 60.

“We continue to take enforcement action against identified boatowners who fail to register their boats.”

An RYA spokesperson said: “Abandoned boats can cause a range of environmental issues, and it’s something we’re genuinely concerned about.

“To tackle this challenge, we need solutions that truly support a circular economy—this means working together with the wider composites industry to make meaningful progress.

“Regulations around end-of-life boats should focus first on re-using, refurbishing, and upgrading older vessels to extend their life, following the waste hierarchy.

“At the same time, we urgently need sustainable recycling methods for fibre-reinforced plastic (FRP) hulls, as well as smarter boat designs that consider what happens at the end of a boat’s life.

“We believe recycling should be funded through extended producer responsibility, so the environmental impact is addressed at its source, in line with the ‘polluter pays’ principle.

“It’s also important that any regulations consider not only new boats, but the large number of older boats already out there.

“The RYA remains committed to working closely with our partners in the UK and the European Boating Association to support the development of effective solutions and fair, forward-looking regulations.”

Langstone Harbour’s timeline for abandoned boats removal

The first ‘bulk’ removals from Eastney Foreshore, working with Boarhunt recovery services and TJ Waste. Credit: Langstone Harbour

Identify a ‘problem’ vessel and make attempts to contact the registered owner, if there is one.

- Take steps to ensure the vessel won’t sink.

- Post a generic abandoned/wrecked vessel notice outlining the harbour authority’s powers or work with the owner to dispose of the vessel at least cost to them.

- Determine which power is most suitable. Rob says laws relating to end-of-life vessels are convoluted and local.

- Follow correct procedure for that power (notices posted, newspaper statutory notices etc).

- To keep costs down, corral a batch of vessels and hire a HIAB truck and low-loader by a local vehicle removals company. Fin keel vessels may require specialist transport.

- GRP vessels transported to local materials recovery centre. (Langstone Harbour pay £240 per tonne at TJ Waste), 20-30% sent waste to energy. Metal yachts sent to recycling centre e.g. Marine & Boat Recycling, a company with an aim of zero to landfill.

Rob says: “They refine the GRP for recycling or waste-to-energy. Their recycling rates look like they will outstrip waste to energy shortly, but it is expensive compared to sending to landfill ourselves.”

University research underway for what to do with slowly rotting hulks

After 30-plus years, many GRP boats remain serviceable. Credit: Langstone Harbour

The University of Plymouth MAterials and STructures (MAST) research group is seeking to establish the extent of the problem, and the environmental consequences, with the goal of developing an appropriate route for handling abandoned, discarded or unwanted glassfibre vessels.

The solution would also be transferable to the problem of end-of-life wind turbine blades and other large composite structures.

The MAST group, in collaboration with AQASS Limited, has published the ‘Sustainability considerations for end-of-life fibre-reinforced plastic boats’ report, which reflects that, in the 1950s, glass fibre-reinforced polyester resin (GRP, also known as fibreglass or glassfibre) composites replaced wood and metal as the material for small recreational and work boats.

The changes resulted from relative ease of manufacture, durability, and low maintenance, however, as thermosetting resin is not easy to recycle, once their design life ends, these boats exist as slowly rotting hulks.

The number of GRP vessels requiring disposal exceeds the capacity of incineration which is usually in energy recovery cement kilns. Credit: John Summerscales

Abandoned boat at Hooe Lake, Plymouth. Credit: John Summerscales

‘Quantification is key’ first step to tackling the abandoned boats problem

“Quantification of the extent of the abandoned and derelict vessels problem is key to developing an effective route to disposal of the boats”, says the university’s Professor of Composites Engineering, John Summerscales, who is one of the authors of the report.

The report finds that ‘incineration with energy recovery in cement kilns is currently the preferred disposal route, but the potential number of vessels for disposal exceeds the capacity.’

It recommends that the ‘implementation of registration should be expedited to enable prompt action when end-of-life boats are identified’, and that the focus should be on reusing composite panels in bicycle- and bus-shelters and boundary fencing, for example, and concludes:

‘In the short term, there is a need to bring the composite materials recovery technologies to the final stage of development (TRL9) and develop markets for the recyclate.’

Given that abandoned and derelict vessels will continue, the report says that a systematic approach for sustainable handling is necessary, and suggests: ‘Given the environmental burdens imposed by the manufacture of GRP systems, funding for disposal schemes might be integrated with decarbonisation support mechanisms to overcome existing technical, financial and market barriers.’

Recycling vs cheap Chinese imports

Recycled GRP planks. Credit: marineandboatrecycling.co.uk

Marine & Boat Recycling, a UK facility with a ‘zero to landfill promise’, has been turning reground end-of-life GRP from boats mixed with recycled plastic into decking and scaffolding planks.

Over the past 15 months, the new business has disposed of 180 vessels, of which it has reclaimed 55% of materials such as ballast, parts, fixings and fittings.

Non-recyclables are sent to waste-to-energy incineration facilities. The £450 a tonne plus VAT cost for disposal is offset by parts that can be reclaimed.

Director Will Higgs said: “For me, this work is about more than recycling boats – it’s about protecting what we love.

“Every vessel recovered is a step toward cleaner seas, healthy coastal communities and a future where nothing is wasted.

“We’re not just changing how boats end, we’re changing where the industry is headed.”

He added: “Any recycling solution must make financial sense if it’s to successfully scale, which is a challenge when virgin glass fibres can be commercially bought for £1.20 a kilo from China.”

A Wayfarer finds a new owner. Credit: boat-disposal.co.uk

A rehomed Signet 20. Credit: boat-disposal.co.uk

Meanwhile, Marine GRP Recycling Ltd, a UK-based end-of-life boat disposal and recycling centre, has “helped save 177 boats” including sailing dinghies, motorboats and yachts, including a 43ft Seawolf since August 2021 by ‘rehoming’ the old boat with a new enthusiast who will take it on for free and restore it.

The company has also disposed of 40-50 boats – with the GRP vessels sent to waste-to-energy facilities.

The cost of re-homing is £250. For scrapping, the cost for a 3-tonne boat is approximately £2,200,

‘I have a lot of sympathy for people who abandon boats’

The crowd-sourced map is trying to quantify the abandoned problem. Credit: wreckfree.org

A new interactive map to report abandoned boats in Fal and Helford attracted 170 entries in a few months.

“That’s probably about half the wrecks on the two estuaries, if you count abandoned boats in boat yards and small boats tucked up in trees,” said Jake Burnyeat, who set up the Wreck-Free Fal and Helford forum.

“Honestly, when you start looking, you find small boats and canoes shoved in bushes, all over the place.”

Abandoned boat in Porth Hellick, St Mary’s, Isles of Scilly. Credit: John Summerscales

Abandoned boat in Hugh Town, St Mary’s, Isles of Scilly. Credit: John SummerscalesCredit: John Summerscales

Jake, who is a keen sailor added: “I have a lot of sympathy for people who abandon boats, because there’s no other easy option.

“There are all sorts of reasons people end up with a boat they can’t manage anymore.

“It might have been a parents’ boat and they’ve died and the kids have got to deal with the problem, or the boat owner has run out of money and there is no easy option for getting rid of them.

“There’s one scrapyard on our estuaries where you can take them – Truro Recycling – and the charge is £500 a ton to take the vessel.

“So, if you’ve got a three ton boat, that’s £1,500 – after you’ve got it there – and the boat is obviously worth nothing.”

The Wreck Free Fal and Helford launch event attracted 100 stakeholders. Credit: wreckfree.org

The volunteer-run forum, established last winter, builds on the “inspirational work” of Sailors Creek CIC that leases the foreshore of the creek near Flushing and cleared out 57 tons of marine waste and nine old vessels, and the “amazing work of Steve Green and Monika Hertlova from Clean Ocean Sailing”, who have been clearing wrecks around the Fal and Helford with donation-based money from crowdfunding.

The forum achieved its first objective to produce a map and database of the abandoned vessels around the Fal and Helford to quantify the problem thanks to “an amazing retired computer programmer from Birmingham”, who voluntarily created the map and database that allows members of the public to report a wreck, upload photographs, add location and vessel details.

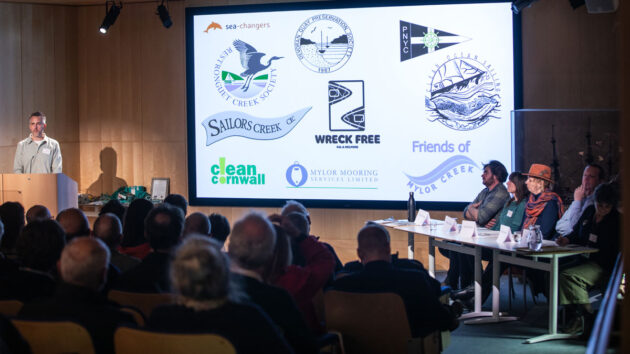

The forum launch event in February, at the National Maritime Museum, Cornwall, attracted 100 attendees including representatives of harbour authorities, mooring operators, foreshore owners, yacht clubs, statutory bodies, environmental groups and other stakeholders.

Sailors Creek turnaround

Before… mandatory boat registration could help to avoid ‘a mess’ like this. Credit: www.sailorscreekcic.org

Now… better access and hard work transformed Sailors Creek on the Fal. Credit: www.sailorscreekcic.org

Leasing two fields that had reverted to scrub was a “game changer” for clearing the mess of Sailors Creek based near Flushing in Cornwall, as enabled the build of a trackway to reduce the cost of rubbish removal.

In the past five years, the Sailors Creek Community Interest Company (CIC) have reinstated 26 beach berths, planted a Forest Garden, removed nine end of life vessels and more than 57 tonnes of flotsam, jetsam and marine waste.

Director Emma McGee said: “Much of our success has been volunteer-led and self-funded, supported by small grants, crowdfunding, membership contributions, and now a small income from fair-value moorings, as we carefully reinstate them.

“We repurposed mussel tubes to create safe, floating walkways for boat access. From late summer 2025, we’ll begin installing reedbeds on our pontoons to aid greywater filtration—part of our ongoing commitment to environmental restoration.”

In the creek, three wrecks where removal was not viable are being upcycled in situ to support access infrastructure: One is being transformed into a community tea shed and work area. Another will become a floating garden.

The third is Keewaydin, a 1913, 100ft Rye-built wooden champion sailing trawler, is being made watertight by volunteers and skilled shipwright Spike Davies, the aim is to launch her from the rusting barge she’s currently stranded on.

Emma said: “We hold a license, which enabled us to extract nine end-of-life vessels from the creek once we had cleared them of pollution.

“Most were cleaned, made safe, and delivered to Glastonbury Festival’s Pop-Up Hotel, where they now serve as community seating areas.

“Others are being creatively repurposed as features within our developing forest garden.

“Two, which were unsalvageable, were taken to landfill.”

Credit: www.sailorscreekcic.org

She added: “In February, we participated in the inaugural Wreck Free Fal and Helford Forum at the National Maritime Museum Cornwall, helping raise national awareness of the scale and challenges of derelict vessels.

“Like others at the forum, we support the French model of boat disposal, where a modest manufacturer levy and boat registration fee fund dismantling infrastructure.

“We’d encourage PBO readers to report abandoned boats using www.wreckfree.org and to join the campaign to tackle the, often underestimated, growing issue of abandoned boats.

“Collaboration is key. Local knowledge, volunteer input, and hard work from other volunteer groups like Clean Ocean Sailing have been essential in making a difference in our corner of the world.”

How much does a free boat really cost?

Richard Rogers reveals the true cost of how much he spent rebuilding his ‘free’ yacht, and asks if it has…

Wreck to Transat racer

Is racing across the Atlantic in a boat bought with a student loan really feasible? Here's the story of PBO…

First evidence of GRP boats’ “cancerous” impact on aquatic life

The ‘really worrying’ findings by University of Brighton researchers who undertook studies off the coast of Hampshire and West Sussex…

Want to read more articles like ‘Abandoned boats and end-of-life vessels – a growing problem’?

A subscription to Practical Boat Owner magazine costs around 40% less than the cover price.

Print and digital editions are available through Magazines Direct – where you can also find the latest deals.

PBO is packed with information to help you get the most from boat ownership – whether sail or power.

-

-

-

- Take your DIY skills to the next level with trusted advice on boat maintenance and repairs

- Impartial, in-depth gear reviews

- Practical cruising tips for making the most of your time afloat

-

-

Follow us on Facebook, Instagram, TikTok and Twitter