John Savage argues that the Beaufort Scale needs an update to make it more simple

Sailors tend to understand the basics of the Beaufort Scale, but how many of us know it verbatim?

And that is the problem. How many of us actually know the scale or could quote it from memory?

The Beaufort Scale is a wonder of meteorological description, but it is not easy to recall and, more importantly, it is difficult to teach making it just another obscure sailing eccentricity for novice sailors to learn.

Sir Francis Beaufort created his famous scale in 1805; it received international recognition in 1874. Credit: SSPL/Science Museum Getty

Have you ever been sailing and thought that 11 knots does not really feel like the same sailing condition as 16 knots, or that while you like the Beaufort Scale, you cannot remember the limits of each force, so you just use the knots reading from the wind gauge in the log book? If so, you are not alone, and what is more, you are not to blame either – history is. Having had these same thoughts, I did some research and found an old, contrary mistake.

Created in 1805 by Francis Beaufort (later Admiral Beaufort) while serving aboard HMS Woolwich, the Beaufort Scale was devised as a way of describing wind speed. Initially, it used descriptive terms, such as:

0 Calm;

1Faint air, just not Calm;

2Light airs;

3Light breeze

all the way up to

11 Hard gale;

12Hard gale with gusts;

13 Storm.

By 1838, and its formal adoption into the Royal Navy, it had been changed to a more objective scale: referencing the amount of sail a ‘well-conditioned man of war, under all sail, and “clean full”, could carry close hauled…’. It assisted mariners in the logging of weather conditions and general sail planning.

At the time, weather logging was not standardised, anemometers did not exist, and there was no central body regulating terms. It was not until 1905 that the British Met Office (the Met Office) formalised the limits of each force.

The scale’s clear benefits aside, the Beaufort Scale has always struck me as somewhat alien; it lacks any pattern, rhythm or rhyme to its numbers and ranges, it is difficult to teach, and (other than by rote) is seemingly impossible to memorise. The scale’s lack of rhythm and peculiarity of construction make it hard to instruct, and for those new to sailing, it is another piece of peculiar terminology.

Simplifying The Scale

For many years I tried to find a way to simplify the recollection and teaching of the scale, but neither ‘easy-to-remember numbers’ nor ‘multipliers’ worked; each method producing different results from the published values.

That said, I believe there is a way, and it comes from identifying a small yet interesting error that may have occurred in the early part of the 20th century, when the Met Office (and later the World Meteorological Organization) began formalising the scale.

Day skippers are not advised to venture out into a Force 6; making the changes between Force 5 and Force 6 will help new skippers remember this. Credit: Michael Blyth

Before explaining the solution, we must first briefly examine the scale itself. As commented on by Messrs Wallbrink and Koek in their article ‘Historical Wind Speed Equivalents of the Beaufort Scale, 1850-1950’, Mr Simpson, who (first in 1905 and later in 1926) had been tasked by the Met Office to standardise the scale, ‘…then drew a smooth curve by the eye, to be the best fit of the two curves. From this new curve, the successive steps for the new scale were read, thus ensuring that the steps increased regularly over the whole scale.’

Considering Beaufort’s original intent and the work of Simpson in harmonising the various versions of the scale that had developed over time, we should be able to agree on two ‘Beaufort Principles’, which help ensure the Beaufort Scale remains relevant and useful.

Firstly, each force should cover a range of wind that generally aligns with an observable sailing condition and sea state. For example, Force 5 might be ‘jib and two reefs in the main’, with a sea state of Moderate.

Secondly, the range of wind speeds within each force should not reduce as the force increases. This reflects the practical experience that a change of 3 knots, eg from 2 to 5 knots (Force 1 to Force 2), is clearly more significant than the same 3 knots increase between 42 and 45 knots (both Force 9).

The official Beaufort Scale

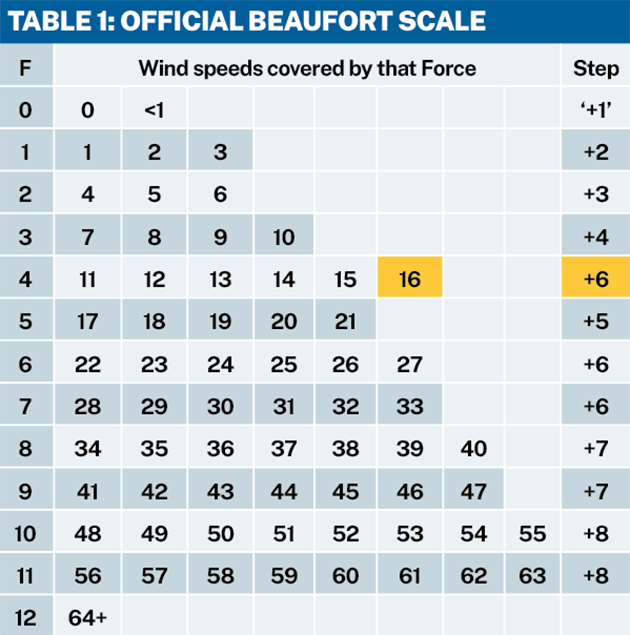

Table 1 (above) is the official Beaufort Scale as maintained by the World Meteorological Organization. The wind speeds have been laid out so we can identify the pattern – or lack thereof.

Following the ‘Beaufort Principles’, the range of wind speeds covered by higher Beaufort forces should be greater than for lower forces. As you can see, this is true for all but Force 5, which covers a smaller range than Force 4. With one small change, we can fix this problem and also establish an easy and simple means of remembering the scale.

The right hand column in Table 1 lists, the range for each force, which has this pattern: +1, +2, +3, +4, +6, +5, +6, +6, +7, +7, +8, +8.

Again, the ‘short’ Force 5 breaks the mould.

A Simple, Logical, And Beneficial Change

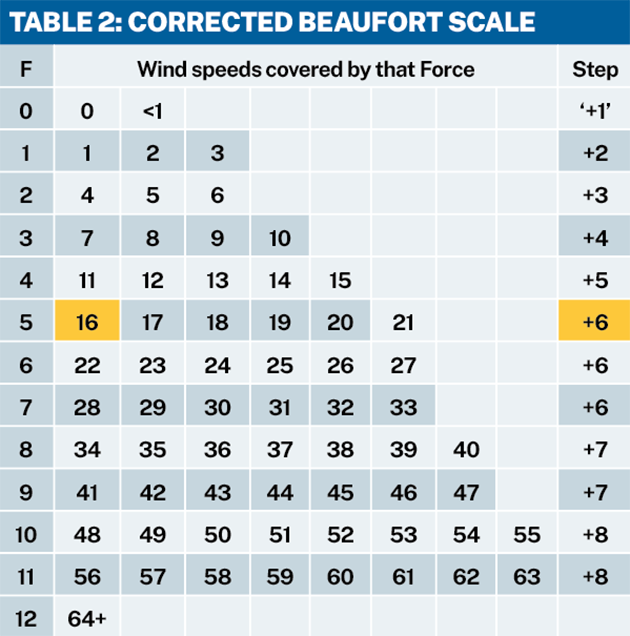

If 16 knots is moved into Force 5, we have the benefit of making Force 4 smaller in range compared to Force 5 (making Force 5 a little more relevant); we also create a pattern that becomes simple to teach and easy to remember.

Corrected Beaufort Scale

Table 2 (above) shows the ‘corrected’ table. This seemingly small change immediately simplifies the way that the Beaufort Scale can be taught. Now that we have corrected the ranges, the pattern is much simpler:

■ Force 0 to Force 5: +1, +2, +3, +4, +5, +6 (pleasant sailing).

■ Force 6 to Force 12: +6, +6, +7, +7, +8, +8 (less pleasant sailing).

This change corrects an error that has been present since 1906 and aligns with the WMO’s formulaic definition of the Beaufort scale. If we also consider that the scale is first taught to Competent Crew and Day Skipper candidates, then we can make it more convenient still by adding a notional divide between Force 5 and Force 6; a natural break for a Day Skipper as it is ill-advised for new Day Skippers to venture out into a Force 6 (Strong Breeze), aka the ‘Yachtsman’s Gale’.

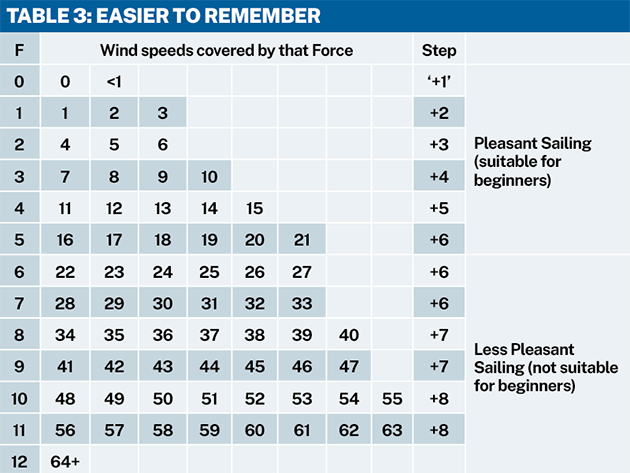

Easier to remember Beaufort Scale

This convenient means of instruction and recollection, is shown in Table 3 (above). These changes make teaching much easier, as a simple phrase/methodology can be used.

For novices who only need to remember up to Force 5, we can use the following method:

■ The upper bound of a Force is the sum of all numbers from F0 to F+1 .

■ For example, Force 5 goes up to 1 + 2 + 3 + 4 + 5, + 6 = 21 knots

In practice, this is easily done by counting on your fingers until the required Force (or Force + 1) is shown.

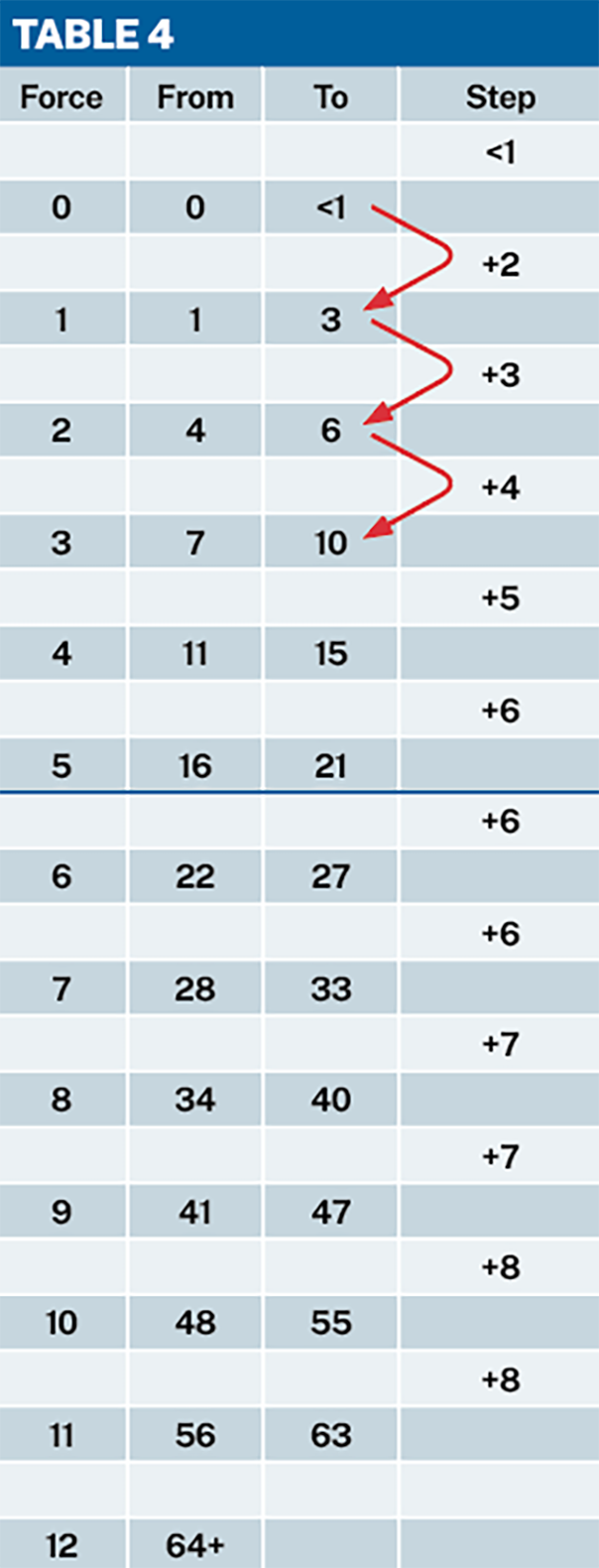

The full Beaufort Scale can be jotted down simply by:

1. Write the headings: Force, From, To, and Step

2. Under Force write 0-12

3. Under Step write <1, +2, +3, +4, +5, +6, then +6, +6, +7, +7, +8, +8

4. For the To column, cumulatively add the Step column, for example, 0 + <1 = <1, 1 + 2 = 3, 3 + 3 = 6, 6 + 4 = 10 …

5. From: use the next integer above the previous upper limit.

This article is based on a full and comprehensive research paper that looks at the formulaic foundation of the scale, its relationship with other units of speed and much more. The full paper is available at: www.aswts.wordpress.com/beaufort

The Met Office Says

The Beaufort Scale was developed from 1806 to 1807 to enable consistent, quantified measurement of wind force and was widely adopted. The diaries of Admiral Beaufort remain one of the most significant items in the collection of the National Meteorological Archive. The scale has been in use for over 200 years and provides a long and consistent means of measuring wind force, which is of immense value to weather and climate modelling.

Lying ahull or heaving to? Which is best for heavy weather?

Experienced ocean sailor Tim Cassidy advocates lying to the wind with no sail set in heavy weather, but stresses the…

Preparing a small boat for heavy weather with advice from the skippers of the Jester Challenge 2025

The Jester Challenge 2025 once again proved a fertile ground for examples of how a short-handed crew can prepare for…

Understanding weather: a quick guide for sailors

Only the foolhardy would put to sea without first checking the weather and forecast – understanding how to make use…

Sail trim: Sailing downwind without a spinnaker

Sailing efficiently when the wind comes astern doesn’t mean you have to fly a spinnaker or cruising chute. David Harding…

Want to read more articles on seamanship?

A subscription to Practical Boat Owner magazine costs around 40% less than the cover price.

Print and digital editions are available through Magazines Direct – where you can also find the latest deals.

PBO is packed with information to help you get the most from boat ownership – whether sail or power.

-

-

-

- Take your DIY skills to the next level with trusted advice on boat maintenance and repairs

- Impartial, in-depth gear reviews

- Practical cruising tips for making the most of your time afloat

-

-

Follow us on Facebook, Instagram, TikTok and Twitter