The Marine Accident Investigation Branch (MAIB) report into the loss of the yacht Cheeki Rafiki and its four crew in the Atlantic Ocean, approximately 720 miles east–south-east of Nova Scotia, Canada on 16 May 2014.

Almost a year after the sailing community was shocked by the sudden and tragic loss of the British sailing yacht Cheeki Rafiki and its four-man crew, the findings of an official investigation have been published.

MAIB synopsis

At about 0400 on 16 May 2014 the UK registered yacht Cheeki Rafiki capsized approximately 720 miles east-south-east of Nova Scotia, Canada while on passage from Antigua to Southampton.

Despite an extensive search that found the upturned hull of the yacht, the four crew remain missing: Skipper Andrew Bridge, aged 21, from Farnham, Surrey and crew Paul Goslin, 56, from West Camel, Somerset; Steve Warren, 52, from Bridgwater, Somerset and 22-year-old James Male from Romsey, Hampshire.

At approximately 0405 on 16 May an alert transmitted by the personal locator beacon (PLB) of Cheeki Rafiki’s skipper triggered a major search for the yacht involving United States Coast Guard fixed-wing aircraft and surface vessels.

At 1400 on 17 May, the upturned hull of a small boat was located; however, adverse weather conditions prevented a closer inspection and the search was terminated at 0940 on 18 May.

At 1135 on 20 May, following a formal request from the UK government, a second search was started. At 1535 on 23 May, the upturned hull of a yacht was located and identified as being that of Cheeki Rafiki.

On investigation, it was confirmed that the vessel’s liferaft was still on board in its usual stowage position. With no persons having been found, the second search was terminated at 0200 on 24 May. Cheeki Rafiki’s hull was not recovered and is assumed to have sunk.

In the absence of survivors and material evidence, the causes of the accident remain a matter of some speculation. However, it is concluded that Cheeki Rafiki capsized and inverted following a detachment of its keel.

In the absence of any apparent damage to the hull or rudder other than that directly associated with keel detachment, it is unlikely that the vessel had struck a submerged object. Instead, a combined effect of previous groundings and subsequent repairs to its keel and matrix had possibly weakened the vessel’s structure where the keel was attached to the hull.

It is also possible that one or more keel bolts had deteriorated. A consequential loss of strength may have allowed movement of the keel, which would have been exacerbated by increased transverse loading through sailing in worsening sea conditions.

Cheeki Rafiki’s upturned hull taken by the crew of USS Oscar Austin in the afternoon of 23 May 2014. Courtesy of US Coast Guard

Action taken

The yacht’s operator, Stormforce Coaching Ltd, has made changes to its internal policies and has taken a number of actions aimed at preventing a recurrence. The Maritime and Coastguard Agency (MCA) has undertaken to work with the Royal Yachting Association (RYA) to clarify the requirements for the stowage of inflatable liferafts on coded vessels, and the RYA has drafted enhancements to its Sea Survival Handbook relating to the possibility of a keel failure.

A recommendation has been made to the British Marine Federation to co-operate with certifying authorities, manufacturers and repairers with the aim of developing best practice industry-wide guidance on the inspection and repair of yachts where a glass reinforced plastic matrix and hull have been bonded together.

A recommendation has also been made to the MCA to provide more explicit guidance about circumstances under which commercial certification for small vessels is required, and when it is not.

Further recommendations have been made to sport governing bodies with regard to issuing operational guidance to both the commercial and pleasure sectors of the yachting community aimed at raising awareness of the potential damage caused by any grounding, and the factors to be taken into consideration when planning ocean passages.

MAIB chief inspector Steve Clinch said: ‘This has been a challenging investigation. Cheeki Rafiki capsized and inverted, almost certainly as a consequence of its keel becoming detached in adverse weather, in a remote part of the North Atlantic Ocean.

‘Despite two extensive searches, its four crew remain missing and, as the yacht’s hull was not recovered, the causes of this tragic accident will inevitably remain a matter of some speculation.

‘Nevertheless, a thorough investigation has been conducted, that has identified a number of important safety issues, which if addressed, should reduce the likelihood of a similar accident in the future.

‘The investigation has identified that in GRP yachts that are constructed by bonding an internal matrix of stiffeners into the hull, it is possible for the bonding to fail, thereby weakening the structure.

‘In some yachts, including the Beneteau First 40.7, the design makes it harder to detect when the bonding is starting to fail. The report therefore highlights the need for regular inspections of such yachts’ structures by a competent person, and for the marine industry to agree on the most appropriate means of repair when matrix detachment has occurred.

‘During the investigation it became clear that opinions were divided as to whether or not Cheeki Rafiki’s return passage across the Atlantic Ocean was a commercial activity.

‘I have therefore made a recommendation to the Maritime and Coastguard Agency to improve the guidance on when small vessels are, or are not required to have commercial certification. This should help resolve what has, for too long, been a grey area.

Finally, I hope that this report will serve as a reminder to all yacht operators, skippers and crews of the particular dangers associated with conducting ocean passages, and the need for comprehensive planning and preparation before undertaking such ventures.

‘On long offshore passages, search and rescue support cannot be relied upon in the same way as it is when operating closer to the coast, and yachts’ crews need a much higher degree of self-sufficiency in the event of an emergency. Thus the selection and stowage of safety and survival equipment needs to be very carefully considered before embarking, together with options for contingency planning and self-help in anticipation of problems that could occur during the passage.’

Cheeki Rafiki had been sailing back to its base port of Southampton, following the completion of Antigua Sailing Week, held from 27 April to 2 May 2014.

The report states that: ‘Cheeki Rafiki and its crew won Antigua Sailing Week’s Beneteau First 40.7 class. The vessel reportedly sailed very well during the week, with no reported defects or water ingress to the hull.’

Extracts of email and voice communications between Cheeki Rafiki’s skipper and the Stormforce Coaching’s principal/director include:

Monday 12 May 2014

1750 – email, from Cheeki Rafiki

‘Cheeki Rafiki Blog Update. It has been 9 days at sea and we are all fairing well,

the winds have been gentle whilst routing up northwards to the Eastern side of Bermuda. And yesterday we did it…we turned East for home and completing our first 1000 miles…We have had one stormy morning so far with beating rain and a force 5 wind which lasted a few hours, but we are still enjoying plenty of sunshine and warm temperatures…position update 34 24’N 056’ 55W 1700 UT 12.05.14’ [sic]

Wednesday 14 May 2014

1014 – email, from Cheeki Rafiki

‘position update at 1000ut 37 00N 052 05W 24hour run 176miles…just hit a big

wave hard and it fixed the stereo.’ [sic]

Thursday 15 May 2014

2022 – email, from Cheeki Rafiki

‘we have been taking on a lot of water yesterday and today. today seems worse i think stbd water tank has split so that is drained checked hull and sea cocks for damage but cant see any. i will go for a swim when weather improves in about 24 hours we are currently monitoring the situation horta is 900 miles away. our position is 38 38N 048 59W any thoughts from your end i will check emails in 2 hours’ [sic]

No further data connections were made on board Cheeki Rafiki and so no further emails were received by the vessel.

2046 – email, from Stormforce Coaching (not received by Cheeki Rafiki)

‘Is any water fresh or salty? That will tell u most if what u need to know’ [sic]

2048 – email, from Stormforce Coaching (not received by Cheeki Rafiki)

‘Loosen straps for liferaft. Check epirb and sat phone are accessible etc. Have everything ready in case of worst case’ [sic]

2221 – 55 seconds’ duration satellite telephone voice call from Cheeki Rafiki’s skipper to Stormforce Coaching’s principal/director and 2 minutes 46 seconds’ duration return call on a different mobile telephone owing to low battery power.

The skipper described the situation (ie water ingress) as worse than before and that the water had been identified as sea water, the engine bilge had been found to be dry and that the leak could not be found.

2230 – email, from Stormforce Coaching (not received by Cheeki Rafiki)

‘I need your position’

2233 – attempted satellite telephone voice call from Stormforce Coaching’s principal/ director to Cheeki Rafiki (redirected to voicemail)

2246 – telephone call from Stormforce Coaching’s principal/director to Maritime Rescue Co-ordination Centre (MRCC) Falmouth advised that Cheeki Rafiki was taking on water and that the pumps were coping with the ingress; the vessel’s

2022 position was also given.

2332 – email, from Stormforce Coaching (not received by Cheeki Rafiki)

‘I have spoken with Falmouth Coastguard who will in turn talk to the Yanks as

you are within their SAR region. They have you sat phone number, email etc.

In terms of the leak you need to focus on 3 things. Finding the leak, reducing the rate of ingress and getting rid of water on board.

It added:

Worth having a look at the keel bolts and make sure there is no cracking around them.

I would like to set up a 4 hour comms interval. Where you call me every 4 hours and confirm all OK or otherwise. I will leave you to make the first call to my mobile tonight on…After that will go for 4 hour intervals until you tell me problem is solved. I have my mobile with me and will keep it free….

Needless to say make sure everyone is wearing a LJ at all time, make sure the life raft and grab bag/water are ready and make sure if things get worse the EPIRB and sat phone are to hand and the sat phone is charged.

You are currently in a USA Search and Rescue area but out of range of aircraft. If you had to abandon then merchant vessels would be requested to divert to you.

Please keep us updated of you position, weather you are experiencing, ETA Azores, fuel reserves and the state of water ingress?’ [sic]

2349 – attempted satellite telephone voice call from MRCC Falmouth to Cheeki Rafiki (redirected to voicemail)

Friday 16 May 2014

0330 – 1 minute 42 seconds’ duration satellite telephone voice call from Cheeki Rafiki’s skipper to Stormforce Coaching’s principal/director

Stormforce Coaching’s principal/director had difficulty understanding what Cheeki Rafiki’s skipper was saying, but he understood the skipper to be saying, “this is getting worse”. The principal/director told the skipper to check his emails, which he acknowledged.

Cheeki Rafiki‘s approximate position at this time was 38o 37.0N 048o 06.7W.

Thereafter, the satellite telephone was no longer connected to the satellite and no further signal was received from it.

At 0633, following an initial alert at 0629, a second PLB alert with positional data was received by RCC Boston.

The alert was from the mate’s PLB and was received about 8 minutes before the final satellite-detected position received from the skipper’s PLB. The mate’s PLB position resolved at 0713 as approximately 0.5 mile from the last satellite-detected position received from the skipper’s PLB.

At 1100, the HC-130 aircraft arrived on scene and commenced a search based on three drift calculations for: a swamped 39 foot (11.9m) sailing vessel, a liferaft and a person in the water.

During the search, the aircraft’s crew identified some small debris, including what was possibly a small white lifebuoy, a boat fender, pieces of shiny white wood and other miscellaneous items.

The search effort continued utilising HC-130 aircraft from the USCG, the US Air Force, and the Royal Canadian Air Force, and three merchant vessels. It initially concentrated around the PLB alert locations.

At 0940 on 18 May 2014, the search effort was terminated.

RCC Boston calculated the estimated survivability of the crew members based on their average descriptions, assuming that they were dressed in full foul weather sailing gear, immersed to the neck in water and wearing a personal flotation device (PFD). Using these criteria, the estimated functional survivability and survival times were 12.3 hours and 15.5 hours respectively.

At 1135 on 20 May 2014, the search effort resumed following a formal request from the UK government. The second effort was again co-ordinated by RCC Boston, and the first search and rescue (SAR) assets began to arrive later that day. During this period, aircraft from the USCG, US Air Force, Royal Canadian Air Force and UK Royal Air Force, nine merchant vessels, United States Coast Guard Cutter (USCGC) Vigorous, United States Ship (USS) Oscar Austin and numerous additional yachts took part in the search.

At 1553 on 23 May 2014, USS Oscar Austin’s embarked helicopter located an upturned yacht’s hull. The vessel launched a small boat with a surface swimmer, who positively identified the hull as being that of Cheeki Rafiki and confirmed that its liferaft was still on board in its usual stowage position.

At 0200 on 24 May 2014, the SAR effort was terminated.

MAIB enquiries to GRP repairers and Beneteau First 40.7 owners

During the course of the investigation, the MAIB received much anecdotal evidence regarding matrix detachments on Beneteau First 40.7 yachts. Areas notable for detachment were in the forward sections of the matrix, commonly attributed to the vessel slamming, and the area around and aft of where the keel is attached to the hull, commonly attributed to the vessel grounding.

MAIB inspectors visited four Beneteau First 40.7 yachts that had all suffered detachments of their matrix in bays around the aft end of the keel as a result of grounding. Additionally, two of these vessels had suffered, or were showing signs of, matrix detachment in the forward section.

One further Beneteau First 40.7 yacht was visited, which showed signs of matrix detachment in the forward and aft sections.

The crew’s PLBs

The skipper had with him a Kannard Safelink Solo PLB, which had been registered with the MCA in November 2013.

The mate had with him a McMurdo Fastfind 220 PLB, which had been registered with the MCA in April 2014. Both PLBs were waterproof and were provided with a buoyancy pouch and lanyard to prevent their loss when in water.

They were both fitted with an integral global positioning system (GPS) transmitter capable of transmitting for a minimum of 24 hours once activated. Both units were manually operated and had to be held clear of the water with their antenna vertical to be able to transmit an alert.

Related articles

- Cheeki Rafiki tragedy: was structural failure to blame?

- Cheeki Rafiki life raft ‘was not used’

- Debris sighted during the search for Cheeki Rafiki

- ARC Europe yacht Malisi joins search for missing Cheeki Rafiki crew

- Sailors’ Cheeki Rafiki fund for RNLI hits £20k in less than 24 hours

- Growing call for US Coast Guard to resume search for British yachtsmen

Conclusions

The report concludes that it is difficult to readily identify areas where a matrix detachment has occurred in GRP yachts manufactured with a matrix bonded to the hull. This is especially the case where the keel is not removed prior to inspection and where floors have been layed up between frames.

It is possible that some of Cheeki Rafiki’s reported ‘light’ groundings could have significantly affected the integrity of the matrix attachment in way of the keel.

There is currently no industry-wide guidance on appropriate methods for identifying matrix detachment and conducting repairs, or on the circumstances that would necessitate keel removal.

Matrix detachment had previously occurred in Cheeki Rafiki, probably in bays immediately either side of the bays where the keel was bolted to the hull. It is therefore possible that detachment had also occurred in way of the keel but had not been detected because of the clamping effect of the keel bolts.

Had Cheeki Rafiki’s structure where the keel was attached to the hull been weakened as a consequence of previous groundings, this might have allowed movement of the keel due to transverse loading in the prevailing sea state, resulting in its becoming detached from the hull. It is also possible that the keel bolts had deteriorated.

It is probable that the increasing risk of Cheeki Rafiki’s keel becoming detached and the danger of continuing on the same approximate course without reducing speed had not been recognised.

Given the remote location of Cheeki Rafiki at the time of its loss, the crew’s survival was largely dependent on being able to deploy to a liferaft in addition to activating an alert.

In the event of a yacht capsizing and then inverting in circumstances in which survival is dependent on liferaft availability, it is vital that every effort is made to ensure that a liferaft remains readily accessible and capable of being deployed for use quickly and easily.

Other safety issues relating to the accident

It is possible for matrix detachment to occur in GRP yachts manufactured with a matrix bonded to the hull, resulting in loss of structural strength. The probability of this occurring will increase with more frequent and harder yacht usage.

Report recommendations

The practice of allowing a vessel to ground during training and examinations has the potential for candidates to underestimate the likely consequences of grounding.

Although the conditions prevailing at the time of Cheeki Rafiki’s loss were theoretically within the design parameters of the yacht, it would have been prudent to have taken action to avoid the forecast high winds and rough seas.

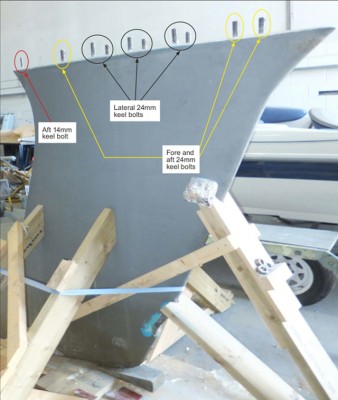

The Beneteau First 40.7 keel washer plates would have needed to be 3mm thicker and 3mm wider for the design, incorporating only one 14mm bolt, to fully meet ISO 12215-9, today’s harmonised ISO standard for keel design and attachment.

Following the tragedy, Stormforce Coaching has made the following changes to its internal policies/taken the following action:

- All staff and crew on races or motor/sail training courses who travel more than 60 miles from a safe haven are required to carry a PLB.

- An external professional weather forecaster and router is to be engaged for ocean passages.

- In addition to regular visual inspections and inspection following a grounding, all ocean-going yachts are to undergo an annual third-party external survey.

- Unless participating in a race, yachts on ocean passages are to endeavour to sail in close company with another yacht, with skippers establishing a formal reporting schedule prior to departure.

- Liferaft stowage locations on all newly acquired yachts that will spend extended periods more than 60 miles from a safe haven are to be reviewed to ensure that the liferaft can be launched in the event of an inversion.

- Where appropriate stowage is available, existing 12-person capacity liferafts on yachts capable of venturing offshore are to be replaced with two 6-person capacity liferafts.

- Rudders on sailing yachts capable of venturing offshore are to be painted day-glow orange to assist with their location in the event of an inversion.

- Lifejackets with retrofitted spray hoods carried on yachts that are likely to

venture more than 60 miles from a safe haven have been replaced with

new 190N lifejackets fitted with an integral spray hood. - A second EPIRB in a float-free location has been fitted on yachts that are

likely to venture more than 60 miles from a safe haven. - All fleet maintenance reporting, recording and planning are now managed

using online cloud-based software. - An ‘out of the water hull inspection’ policy is now documented in the

company’s operations manual.

The MAIB report found that Cheeki Rafiki’s Category 2 certification had been allowed to lapse, and so no authorised person had examined the vessel since its coding survey in 2011. It is possible that any indications of a potential structural problem might have been identified had the annual examinations required by the SCV Code been conducted by an authorised person.

The report also states that had an additional person on board Cheeki Rafiki held an RYA/MCA Yachtmaster Ocean or Yachtmaster Offshore certificate of competence, the skipper would have had a suitably qualified and experienced person immediately available with whom he could have consulted on matters relating to the passage, weather and subsequent events.

It is unknown why neither the skipper’s nor the mate’s PLB transmitted for its design minimum of 24 hours. However, in the wind and sea conditions following Cheeki Rafiki’s loss, manually operating a PLB and then holding it in the required position for a substantial period of time would have been difficult.

The RYA and the International Sailing Federation are both recommended to:

- Issue advice to owners and skippers of pleasure yachts, and to the yachting community in general, that:

- Raise awareness of the potential consequences of running aground, and the need to carry out an inspection following any grounding incident, taking into account the danger of potential unseen damage, particularly where a GRP matrix and hull have been bonded together.

- Highlight the benefits of regular inspections of a vessel’s structure, the carriage of qualified persons on board, float-free lifesaving equipment, and the carriage of PLBs.