A range of four-speed winches from Pontos is claimed to offer more speed for race boats and more power for cruisers – but do they deliver? David Harding finds out

Winching can be hard work. We winch our sheets, guys, uphauls, downhauls, inhauls, outhauls, halyards and flatteners. We winch our reef pennants, we winch people up the mast and, if we have running backstays, chances are we’ll put them on a winch too.

In fact, almost any line that needs to be adjusted under load and that can’t more easily, economically or efficiently be handled by a multi-purchase tackle is led to a winch. We rely on winches to the point where sailing a typical modern yacht of any size without them would be impossible. They give us a mechanical advantage that sailors in the days of square-riggers could only dream of – but that doesn’t mean they always make life easy.

Getting into gears

It might sound strange to someone from outside the boating industry that most winches have just two gears. When winching in the genoa, for example, we start with a lightly loaded sheet that we want to bring in quickly and we usually end up with a lot of load that has to be wound in slowly. That’s like hurtling down a hill on a bicycle before heading up the next one and soon finding ourselves facing a 1 in 4 – and with just two gears? Surely with a two-speed winch the high gear will be too low to start with and the low gear will soon be too high?

We all know that’s often the case, and it’s the problem that Pontos decided to address with a new range of winches in size 40, 46 and 52 that have not two gears but four. The Grinder winches have two gears that are similar to those of a conventional two-speed winch of the same size, and then two extra higher gears for high-speed line retrieval – all without anyone tailing the sheet. They’re designed for just one pair of hands. The Trimmer winches have the same two ‘standard’ gears but this time the extra two are lower, letting you wind in high loads at low speed with minimal effort.

As well as the Grinders and Trimmers there’s also the two-speed Compact, offering the power of a 45 within the dimensions of a typical 28.

Racing and cruising

On a race boat in any breeze, your priority is to sheet the headsail in as quickly as possible while keeping the crew on the rail. With a conventional winch you start just by tailing, because there’s little load on the sheet. Then, as the load comes on, one person winds as another tails. That means having two people off the rail. More time is often lost when the sheet is wound into the jaws of the self-tailer for the last bit of grinding.

Short-handed cruising sailors face a different challenge. Saving seconds is rarely important: what matters is getting the sail in hard enough for it to be efficient, often with limited muscle-power and after the clew has negotiated the babystay, inner forestay, forward lowers or other obstructions. That’s when you need low-speed grunt; not to find yourself struggling to turn the handle when there’s still a long way to go.

There’s another significant difference between race boats and cruising yachts when it comes to winching. Whereas cockpits on race boats tend to have space around the winches so the trimmers can brace themselves, get their weight over the handle and swing it freely, cruising folk generally prefer to live behind dodgers and sprayhoods which, all too often, get in the way. Sometimes it’s not even possible to rotate the handle through 360°, so you have to pump it back and forth and alternate between low and high gear.

Compounding the problem is the fact that the size or type of winch you would ideally have on a boat might not be what the builder fitted. As with sails, all too often builders will fit what they think they can get away with.

Grinding for speed

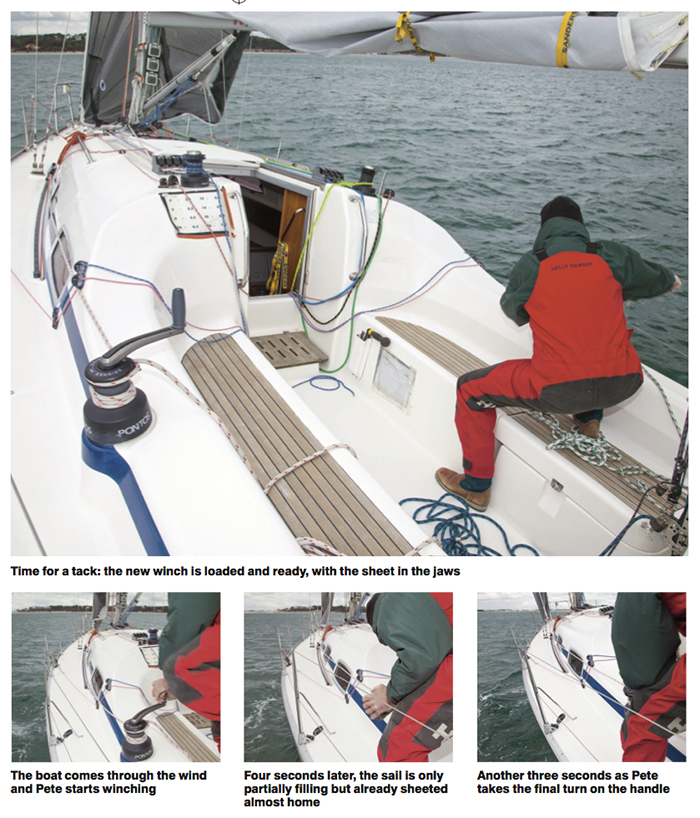

With their Grinder winches, Pontos have designed the highest gear for ultra-fast line retrieval – either for race boats or for cruisers who like to tack quickly. With a gear ratio of just 2.3:1, the Grinder 40 starts by bringing in 27.5in (70cm) of sheet for each turn of the handle. This compares with around 5.5in (14cm) retrieved in high gear by a standard two-speed equivalent. Since there’s no need for tailing, the genoa should be sheeted home before you know it, the trimmer hops back on the rail and you’re fully powered up on the new tack while the competition still has two crew in the cockpit and the genoa halfway in.

You start by taking two to four turns around the drum (depending on the diameter/grippiness of the sheet and the size of the headsail) and then put the sheet into the tailing jaws. During the tack, when the old working sheet has been released and the headsail is coming across, the trimmer (that’s a human trimmer, with a small ‘t’) winds as fast as he or she can in top (fourth) gear by turning the handle anti-clockwise. An arrow on the top of the winch reminds you which way to start.

Because you’re winding in over 2ft of sheet per turn, you will probably have the sail most of the way in before it has even started to fill on the new tack. When the going gets heavy on the handle, you can drop down a gear by reversing direction and winding the other way, just as you would with a conventional winch. This way the gear ratio is 8:1 and you’re bringing in 8in (20cm) with every turn.

Now for the clever bit…

When – if – you’re not yet sheeted fully home and the load on the drum reaches around 130lb/60kg (translating in practice to about 24lb/11kg on the handle), a spring mechanism is triggered that disengages a dog clutch and makes the two lower gears available. A loud click will tell you this has happened.

At this point you can still carry on in third gear for as long as you like. But the click is the signal that reversing the handle to go anti-clockwise again will take you down to second gear, which is equivalent to the higher gear in a conventional winch of the same size (a ratio of 11.6:1, bringing in 5.5in/14cm of line per turn). Should you still not have the sail all the way in, go back clockwise and into first gear. This is equivalent to the lower gear of a normal two-speed 40 (40:1 gearing, retrieving 4cm/1.5in per turn).

So that’s it: load up, wind, reverse handle, wind, reverse handle, and wind and reverse once more if you need to. Job done – fast.

Although some cruising sailors might be drawn to the Grinders, the Trimmers are more likely to appeal because of the ultra-low bottom gear. They followed in the design process when it was realised that reversing the clutch would allow the provision of the two lower gears.

The Trimmers are designed to be handled like normal self-tailers, where you tail the sheet and then wrap it into the jaws. In practice, it goes like this: load up the drum, tail the sheet as the sail comes across, and start winding in top gear (handle anti-clockwise).

This gives you the same ratio as second gear in the Grinder or the higher gear in a normal two-speed winch (11.6:1, 14cm/5.5in line retrieval per turn). When the handle starts loading up, reverse the handle direction to drop down into third gear (40:1, like the lowest gear in the Grinder or a normal two-speed 40).

Now, as with the Grinder, the spring mechanism will be to make the two lower gears available. On the Trimmers it will happen with a drum-load of around 110lb (50kg). After the click – which you might or might not hear if sails are flapping – you have a choice of carrying on in third gear if you like or reversing the handle (turning anti-clockwise) for more grunt.

This is where things are slightly different, because reversing the handle now takes you directly

to first gear, where you have an extraordinary 112.9:1 gear ratio. That equates to just over half an inch (1.4cm) of line retrieved for every turn of the handle. If this is too big a drop, reversing the handle (clockwise again) gives you second gear, or ‘pump’ gear as Pontos call it (32.7:1), because you might well find yourself pumping rather than rotating the handle. Especially if you have dodgers that prevent full rotation, this could be very useful.

It might take a while to get used to the gear sequence of 4, 3, 1, 2, but in practice it works perfectly well. Alternatively, rather than reverse the handle to go from fourth to third as soon as it starts loading up, carry on a little further until you hear the spring click – it doesn’t take much more effort to reach that stage. Reversing the handle then will take you down to second gear instead of third, which isn’t massively different (32.7:1 rather than 40:1). Reversing it for the second time will engage first, so you can treat it as a three-speed winch and go 4, 2, 1. I discovered this just by playing with the winch, and suspect that a lot of people will use it this way.

With the Grinders, the astonishing feature is the speed at which the sheet flies in when you’re in top gear. What will delight users of the Trimmers, especially those who don’t go sailing as an alternative to working out at the gym, is the gearing that converts minimal effort on the handle to such vast pulling power, whether you’re sheeting in the headsail or hauling your husband/wife/crew up the mast (which everyone does, but marine hardware manufacturers stress their equipment should not be used for).

Pontos in practice

For our on-the-water testing, we headed out on a Bavaria 35 Match fitted with two 40s as the primary winches: a Trimmer to starboard and a Grinder to port. For easy fitting and removal without any more holes in the deck they were bolted to base plates, which raised them slightly higher than they would otherwise have been.

More significantly, the largest headsail on the boat had minimal overlap. Ideally we would have been testing with something like a 150% genoa. Nonetheless, the Grinder made the point that it could sheet a headsail home in the blink of an eye once you’ve got the technique.

In this case the technique involved not releasing the old sheet too early, in the interests of maintaining some tension on the new one through the tack. The tension helped keep the sheet

in the tailing jaws as well as preventing riding turns. To be fair, the reason we suffered the occasional rider was that the genoa car was positioned near the forward end of the track, a long way from the winch. This sort of distance will encourage riders with any winch, so in this respect the Pontos winches are no different: the normal sheet-to-drum angle of 5° to 10° applies. A second car further aft on the track would be the answer, and good practice in any event. With the correct lead and nominal tension on the sheet, you can wind in as fast as you like. Grinders have been used successfully on a growing number of race boats in France including several Class 40s, one of which has now covered over 10,000 miles.

The winner of IRC Group 1 in this year’s Round the Island Race used them. Some of the competition, watching from astern, wondered how she managed to tack so slickly. Now they know, and have decided to give themselves the same advantage.

The test rig

We used the Pontos demonstration rig and our own test equipment to measure – among other things – the load on a 10in handle in relation to the load on the drum in various gears.

One finding was that, as winch manufacturers acknowledge, friction and other factors mean that the theoretical gearing doesn’t translate directly to the handle. Nonetheless, Pontos maintain that the way their winches are engineered should help them maintain a greater efficiency ratio, particularly as loads increase.

Listing lots of numbers here won’t necessarily help an understanding of how the winches operate, but here’s an interesting example. We took the Trimmer up to a drum load of 771lb (350kg), which is roughly what you would have on the sheet of a 370sq ft (34sq m) genoa in 22 knots of wind. The force needed to turn the handle in low gear was just 9lb (4kg). No wonder it felt easy on the water.

Further impressive results have included 1st, 3rd and 5th in the recent Cowes-Dinard race – from three Pontos-equipped boats.

Despite the blinding speed of the Grinder, it’s the Trimmer that produced the broadest smiles among our test crew because it makes life so incredibly easy. A young child could sheet home a large headsail in a way that would have been impossible before without an electric winch. If you have been considering going the electric route, Pontos Trimmers might be a much simpler and less expensive alternative.

Compact solutions

We didn’t have one of the new Compact winches to try on the water, but it arrived in time to be bolted to the demonstration rig. Roughly the size of a typical 28, the Compact has two gears: 6.05:1 for rapid line retrieval (10.4in/26.4cm per turn) and then 45:1 (1.4in/3.5cm per turn). Having the same maximum working load (850kg/1,875lb) as the 40s, it should work well on cruisers and racing keelboats up to around 30ft (9m) and has already attracted the attention of some J/24s.

Maintenance and practicalities

The extra gearing inside the Grinders and Trimmers means that they’re slightly larger than conventional equivalents, so they might not fit into recesses or on to plinths that provide no margin. They’re also around 15% more expensive – but if electric winches were the alternative, if you might otherwise have had to change boat or give up sailing, or if race results really matter, you might see that as a small price to pay.

And if you’re a patriotic Brit who rues the decline of our home-grown yacht-building industry but seeks solace in the fact that many French builders fit British hardware, you will be pleased to know that the co-founder of Pontos – a company based in St Malo – is English.

Maintaining the pan- European theme, the winches are made in Italy, in the factory that made Barbarossa and Harken. The pawls are interchangeable with those used by Harken. Handles are standard and the pattern for the mounting holes is that used for Harken Radials – so if that’s what you’re changing from, you’ll be in luck.

Pontos are confident enough to give a five-year warranty, and pulling the winches apart it’s hard to see why they shouldn’t last. For the most part the technology and the materials are tried and tested in winch manufacture. Even the spring mechanism and dog clutch that engage the extra gears will be familiar to engineers: what Pontos have done is to apply established engineering principles in a different way.

Recommended maintenance is to remove the drum and flush with fresh water twice a year. Getting at the pawls if you need to is straightforward enough. If you can service an ordinary winch, a Pontos will not present a challenge.

The more you use Pontos winches, the more you become aware of their potential. If you want speed, go for the Grinders. For incredibly easy power that will allow the less muscular either to get involved in handling the boat or to continue sailing for longer, choose the Trimmers.

Short-handed offshore sailors with the Grinders have found that faster winching with no tailing means less exposure on deck. If you’re a cruising sailor, easier winching with the Trimmers should make life less tiring as well as more efficient because you’ll be able to sheet the genoa in properly. Both have the potential to reduce what the French call the three Fs – froid, faim, fatigue.

They also give you a good reason to fit new winches: you can enjoy the benefits rather than waiting for your old ones to wear out and replacing them with more of the same.

Pontos look set to – yes, we’ll say it but have left it till the end – revolutionise the world of winching. Yet they’re revolutionary in a reassuringly non-radical sort of way. Pontos look like ordinary winches.

They’re made using tried and tested materials and engineering principles in a factory that has made winches for years. They can be taken to bits and put back together. They shouldn’t need much maintenance. They work, and look as though they should carry on working.

Winches aren’t sexy. But when you consider what they mean in terms of how you handle a yacht, winches that do what Pontos have now made them do have the potential to change sailing for the better for an awful lot of people.

Vane gear

Vane gear

Reefing gear

Reefing gear

Hydraulic gearbox

Hydraulic gearbox

PBO Gear

We review hundreds of products to help you make the most informed decision when buying for your boat. Includes outboards,…

Leisure 17: Rescued from the nettles

John MacKenzie finds himself renovating a war veteran’s Leisure 17 that had resided among chest-high nettles in a field in…

PBO Project Boat Handbook on sale

How to turn an eBay wreck into a smart family cruiser - 128 page restoration guide - only £4.99.