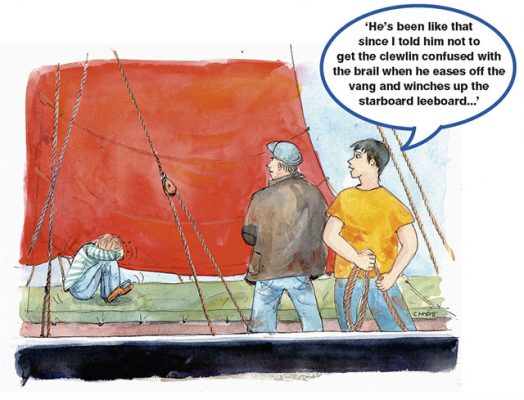

Dave shares hard-won observations, with appropriate terminology, from a ‘modern apprenticeship’ on a Thames charter barge, in his September 2017 PBO column

‘No. Not that one, that one, no, the other one,’ shrieked the first mate calmly as I fumbled with the ropes that led upwards out of sight high up into the ozone layer.

Day two of my ‘modern apprenticeship’ on the Thames charter barge Ground Hog Day was exactly the same; and day three and four, come to think of it. By then the first mate was bellowing even more patiently, and I think he was getting a little bit stressed.

When I asked him what all the ropes were there for, he blurted: ‘Because of reasons.’ That didn’t help. Then he stopped talking altogether.

I helpfully suggested neat little Dymo-tape labels like we have on yots, saying: ‘pull’; ‘don’t pull’; ‘pull only in an emergency’; ‘don’t pull even in an emergency’. Apparently that’s not done on barges.

Still, they say every day’s a school day, and on day five I learned my place: I was promoted into customer care – making tea.

I kinda feel that was a turning point in my life, cos I used to have all sorts of isshoos about me self-esteement and everyfink, but after pulling ropes on a barge I feel I ‘as turned a corner and is mostly going to mostly stop committing crimes altogether, mostly, and become a useful member of society and wotnot and stuff.

But if they don’t give me a barge of me own I could fall back into bad ways and have even worse isshoos. And that would be bad for society, car insurance premiums and other wotnot and stuff and everyfink.

To say the least, helping out on a Thames barge was an education… and a revelation.

Barges, you see, are not like other boats. Their history is fascinating. Most were built in the olden days, although others were built in days of yore, either for the cream-tea trade or the disenchanted yoof turn-around market.

It was dangerous work either way.

In the cream-tea trade, most feared were the scone carriers, as a cargo of wet scones could swell and burst the planks. In the yoof trade, most feared were the social workers.

Article continues below…

Fun boating cartoons from Claudia Myatt

Cartoonist Claudia Myatt has been bringing PBO’s Dave Selby columns to life through comedy boating scenes for more than eight…

Hitch horror and trailer trauma – Dave Selby’s latest podcast

Dave Selby asks 'Why must boat trailers be such a drag?' in his latest column published in Practical Boat Owner…

Berth control for men – Dave Selby’s latest podcast

Dave Selby describes the tortuous boat-handling processes which led to him being rear-ended by a pontoon

Save £££ with boat denial – Dave Selby’s Mad about the Boat

Your expert print-out-and-throw-away guide to free overwintering and hassle-free maintenance, from PBO columnist Dave Selby

Famously, barges were crewed by no more than a man and a boy and a Jack Russell terrier whose job was to yelp piercingly when the barge was about to hit something. That’s why Jack Russells yelp constantly. It’s evolution.

Enough history. Down to practicalities. Barges have ropes everywhere, and some of them do something, but as they’re all the same colour and disappear out of sight into a bundle of orange sails up the mast, there’s no way of telling.

Then there’s the terminology. I was on a spritsail barge, but in Bargish it’s the spreet. There’s also a horse, which isn’t a horse at all but a tree trunk laid horizontally for tripping over, and ropes variously called brails, clew lines, bunt lines and ‘that one’, and it turns out all of these names are interchangeable.

I found out the clew line I was pulling, which is properly termed ‘clew lin’, was actually the brail, which was also the bund line.

There’s also an ‘Essex man’, which isn’t a person at all but an 8:1 purchase for doing something. And then there’s the wang, which sounds totally wong, and is reputed to be even more dangerous than a social worker.

And finally, you’ve got the retractable flippers which are known as ‘lee-boards’.

I’d nearly forgotten the sails. They’re orange. And so beloved are our barges that even to this day fair Essex maidens pay homage by dying their skin orange with the same stuff they use to dress the sails – a fragrant compote of fish guts and creosote.

It’s all pretty straightforward, but more enigmatic are the wonderful names given to barges, for example Minor Fracas, Metaphor, Acronym, Defibrillator, Apostrophe, Catheta, Curmudgeon, Paradox, Reminder, Repertor, Scone, Xylonite and Hydrogen – the last five are real names.

That’s about all there is to know about Thames barges, and the fact that these unique and historic vessels really can be operated by a man and boy and a Jack Russell, as long as one of them’s not me or Bart.

They’re canny craft, a product of the industrial age which produced the gear that reduced each individual task to the strength of a single man or woman. And each one that survives is a tribute to the remarkable commitment of the men and women who keep them going.

If they let me, I’m determined to sort out my isshoos, and when I’ve learned the difference between a clew line and a brail my self-esteement will really be on the up.